Roll Over, Beethoven.

The Second Sunday of Advent.

Lessons from the primary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Isaiah 11: 1-10.

• Psalm 72: 1-2, 7-8, 12-13, 17.

• Romans 15: 4-9.

• Matthew 3: 1-12.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Romans 15: 4-13.

• Psalm 49: 2-3, 5.

• Matthew 11: 2-10.

The Twenty-Ninth Sunday after Pentecost, the Third of Philip's Fast; the Feast of the Holy Great Martyr Barbara; and, the Feast of Our Venerable Father John of Damascus.*

First & third lessons from the pentecostarion, second & fourth from the menaion for the Martyr, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Colossians 3: 12-16.

• Galatians 3: 23-29.

• Luke 17: 12-19.**

• Mark 5: 24-34.

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:50 AM 12/4/2016 — “There is a voice of one crying in the wilderness, Prepare the way of the Lord, straighten out his paths" (Matt. 1: 3; Isaiah 40: 3 Knox). The Holy Evangelist Matthew quoting the prophesy of Isaiah as he introduces us to John the Baptist. 8:50 AM 12/4/2016 — “There is a voice of one crying in the wilderness, Prepare the way of the Lord, straighten out his paths" (Matt. 1: 3; Isaiah 40: 3 Knox). The Holy Evangelist Matthew quoting the prophesy of Isaiah as he introduces us to John the Baptist.

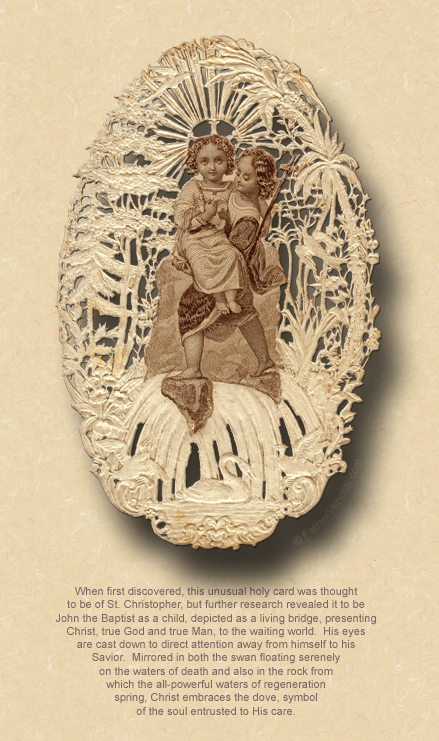

John the Baptist is a transitional figure: his life and his death are clearly part of the Holy Gospel and, as such, he's a New Testament saint; but, he is also the last of the prophets who foretold the coming of the Messiah and, as such, is part of the Old Testament legacy. In this sense, he's kind of like Beethoven, who lived in what musical historians call the Classical period, but whose music was not of that style, and was an anticipation of the Romantic period that would resonate with the music of Tchaikovsky and Saint-Saëns and Rachmaninoff long after Beethoven was dead.

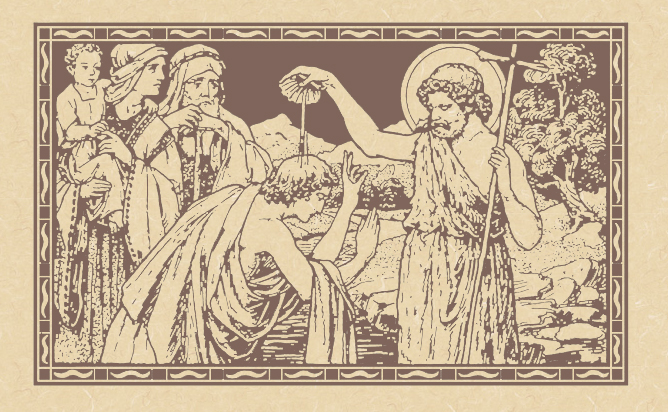

Because he comes before Christ, John cannot yet be said to be a Christian, and what the Evangelist calls his “baptism” was not a sacrament, because there were, as yet, no sacraments. The Evangelist Luke calls it a “baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins” (cf. Luke 3: 3), but it clearly has no power in itself to forgive sins since, without yet a Divine Savior to institute it, then suffer and die and rise again to give it sacramental power, it remains merely a symbol. But symbols themselves can be powerful, and John's purely symbolic baptism was. He invented it out of pure common sense: to clean one's body, one uses water; John used water to represent the cleansing of one's soul, the idea being that one would not present oneself to be baptized by John if one was not ready to acknowledge and confess that one had, in fact, sinned. We don't know for a fact whether John required those coming to him to speak their sins out loud, either publicly or privately to him in secret, but I wouldn't be a bit surprised if he did, since he condemns the Scribes and Pharisees because they won't speak their sins.

The Palestinian Jews and their Roman guests were well used to seeing wandering prophets in the desert, as this was a fairly common phenomenon. What made John stand out from among the ranks of Palestine's corps of desert preachers was what he had to say. Most of the desert prophets spent a lot of their words addressing the situation at hand, namely, Roman occupation. Some of them even had bands of followers committed to various political agendas formed around the preaching of their chosen prophet. Judas Iscariot, so the Gospel tells us, was a member of one such group before he met our Lord. Normally, these kinds of people focused on the problem of the military presence in what the Romans called the province of Galilee.  But John was different. He didn't talk about the Romans, or about freedom for Israel, or about liberation from military rule. Instead, he preached that people should repent of their sins and change their lives. His message did not address the global situation such as it was, but the situation within each man, the state of his soul, how he stood personally before God. And he targeted the leaders of his own religion, not because he challenged their authority, but because he felt they had, themselves, focused so exclusively on the political situation with Rome that they had neglected the spiritual realities which he believed were so much more important. His baptism of repentance became a symbol for those who had cast aside the affairs of this life to focus on what our Lord would call, a couple of years later, the "one thing necessary”: the state of one's soul before God. But John was different. He didn't talk about the Romans, or about freedom for Israel, or about liberation from military rule. Instead, he preached that people should repent of their sins and change their lives. His message did not address the global situation such as it was, but the situation within each man, the state of his soul, how he stood personally before God. And he targeted the leaders of his own religion, not because he challenged their authority, but because he felt they had, themselves, focused so exclusively on the political situation with Rome that they had neglected the spiritual realities which he believed were so much more important. His baptism of repentance became a symbol for those who had cast aside the affairs of this life to focus on what our Lord would call, a couple of years later, the "one thing necessary”: the state of one's soul before God.

And the reaction of many of John's contemporaries to his preaching is typical, and we often see remnants of it today, especially when someone criticizes the religious point of view as trite, or attempts to make the Gospel of our Lord speak to the needs of today by focusing exclusively on what they so pompously call the “social gospel.” This has not changed since before the time or our Lord; and, for those who could not see beyond the pragmatic concerns of this life, John's preaching was very confusing. They did not understand it; and, typical of men in authority, particularly in religion, what they don't understand or can't figure out they ultimately begin to fear as a threat. This is what led to John's death, and what ultimately contributed to our Lord’s death on the cross three years later.

Last week I had mentioned to you how this first part of the Advent Season is focused more on preparing for the Second Coming of Christ who will judge us according to our deeds, and only after December 17th does the Liturgy of the Church begin to prepare us to celebrate our Lord's birth, but the two are intertwined: the Old Testament prophecies we read this time of year can all be interpreted both ways. “A voice cries out,” says the prophet Isaiah as quoted by the Evangelist in today's Gospel lesson: “In the desert prepare the way of the Lord! Make straight in the wasteland a highway for our God!” (Isaiah 40: 3 NABRE). Yes, Isaiah predicts the coming of the Baptist, but he also issues a warning to us: in the desert of your tepid and barren heart prepare a way for your Lord; through the wasteland of your soul which has not thought of divine things, perhaps for many years, prepare a straight highway for your God.

As we progress through this Holy Season of Advent mindful of both of its meanings, the preaching of the Baptist and what happened to him as a result are good subjects for our meditation. We know that the Nativity is the incarnation of God into Man;—His active presence among us—and, in preparing to celebrate it, we must be mindful of preparing ourselves for the Second Coming of our Lord as the Divine Judge who will separate forever the living from the dead.  This entire season of Advent is designed to remind us that, as we prepare ourselves to celebrate Christ’s first coming in the manger, so we should prepare our souls to receive his second. And, at the risk of repeating myself, this means making ourselves right with God, and making ourselves right with God means going to confession, where, in the person of the priest, Christ hears our sins and gives us forgiveness. This entire season of Advent is designed to remind us that, as we prepare ourselves to celebrate Christ’s first coming in the manger, so we should prepare our souls to receive his second. And, at the risk of repeating myself, this means making ourselves right with God, and making ourselves right with God means going to confession, where, in the person of the priest, Christ hears our sins and gives us forgiveness.

It is so easy to be distracted from what’s important, so easy to become preoccupied with the practical concerns that press upon our hearts: our jobs, our health, our relationships, our families and their problems, everything other than how our souls stand before God. In his second epistle, which we read on this day two years ago, the Blessed Apostle Peter vents his frustration at this less than spiritual attitude: he's being peppered with questions about when Christ will come again, and we’ve spoken about this before. Some thought that He would come in their lifetime to deliver them from all their worries, just as some people today treat God like some sort of vending machine: they fire off rosaries and novenas and prayers for this, that and the other, and then just wait for our Lord or our Lady to parachute in and wave their magic hands and make it all better. That never happens, of course, which is when people become testy and angry at God because they missed the whole point of our Lord's life, death and resurrection. The First of the Apostles says:

The Lord is not being dilatory over his promise, as some think; he is only giving you more time, because his will is that all of you should attain repentance, not that some should be lost. But the day of the Lord is coming, and when it comes, it will be upon you like a thief. The heavens will vanish in a whirlwind, the elements will be scorched up and dissolve, earth, and all earth’s achievements, will burn away. All so transitory… (II Peter 3: 9-11 Knox).

Then he asks the question: “Since everything is to be dissolved in this way, what sort of persons ought you to be[?]” Then he answers his own question: “…conducting yourselves in holiness and devotion, waiting for and hastening the coming of the day of God … eager to be found without spot or blemish before him, at peace” (3: 11, 14 NABRE).

John's preaching was rejected because he didn't preach anything anyone wanted to hear: he didn't tell the suffering how God would solve all their little problems; he didn't tell the social agitators how God was going to fix the world. And, when he told them that what was really important was not how God could make all their troubles go away or remake society, but rather that they must repent of their sins and change their lives—not because they were going to be rewarded for it, but because God was coming—that's when they decided they had to do away with him. We can't fall into the same trap, regardless of whether we're obsessed with our own personal problems or trying to remake the life of our Lord into a social program. It isn't our personal problems nor society's problems that should concern us most of all; it's becoming what Saint Peter tells us to be: “…eager to be found without spot or blemish before him, at peace.”

“In the desert [of your heart] prepare the way of the Lord! Make straight in the wasteland [of your soul] a highway for our God!”

* Cf. the first paragraph of the first footnote attached to the post here for an explanation of Philip's Fast. Today is the third Sunday because the season began on a Tuesday.

Legends abound regarding the life and death of St. Barbara, who died during the reign of Emperor Maximianus, and none of these legends can be verified. All that is known for certain is that she was killed by her own father, Dioscorus, because of his hatred for the Christian religion.

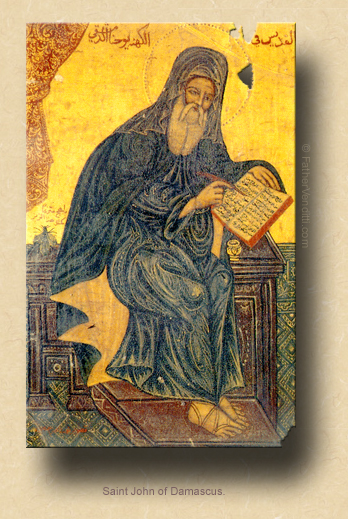

Often referred to as "the last of the Fathers," John Damascene—which is just an anglicized way of saying John of Damascus—formulated much of the theological language we use today to refer to the Perpetual Virginity of the Mother of God, and anticipated the Dogma of the Immaculate Conception centuries before anyone had even uttered those words. Born in Damascus into nobility, he renounced his estate to become a monk in the monastery of St. Sabas near Jerusalem, where he became the first to formulate the theology of the Church in the East according to the Aristotelian method, and scholasticism owes much to these treatises. He died at St. Sabas at an advanced age, probably on this day in 479. Pope Leo XIII declared him a Doctor of the Church.

** Regarding today's lessons from the pentecostarion: ordinarily, due to the "Lucan jump," the Epistle for the 29th Sunday and the Gospel for the 28th would be read today; however, by pure coincidence, both of these lessons are proper to the Sunday of the Forefathers on Dec. 11th, two Sunday's before Christmas. Therefore, both lessons today are replaced by the ones occuring in the post-Pentecost cycle on Dec. 11th which are displaced by the proper readings for the Forefathers. In other words, the lessons from the two Sundays are switched.

For an explanation of the Lucan jump, cf. the second footnote attached to the post here.

|