What's in a Name? For God, Quite a Lot.

The Twenty-Sixth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Amos 6: 1, 4-7.

• Psalm 146: 7-10.

• I Timothy 6: 11-16.

• Luke 16: 19-31.

The Nineteenth Sunday after Pentecost.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ephesians 4: 23-28.

• Psalm 140: 2.

• Matthew 22: 1-14.

The Nineteenth Sunday after Pentecost; the First Sunday after the Holy Cross; and, the Feast of Our Venerable Mother Euphrosyna.*

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• II Corinthians 11: 31—12: 9.

• Luke 5: 1-11.**

FatherVenditti.com

|

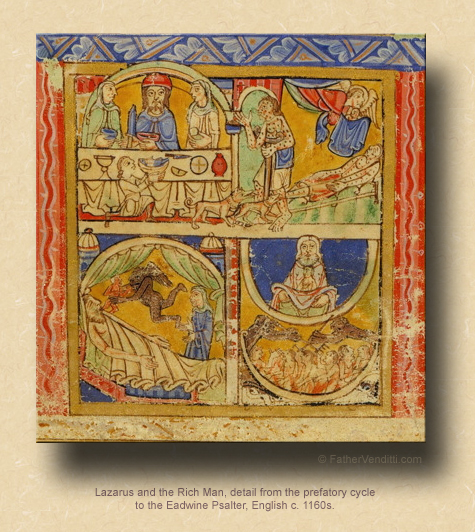

8:44 AM 9/25/2016 — The Roman Missal has its own translation of the Sacred Scriptures which follows very closely what is probably the most common translation of the Scriptures in use among Catholics in our country, called the New American Bible; and, it's unfortunate that we're not permitted to use other translations as is the case in other English speaking countries. As you know, there are a plethora of translations of the Bible into English; some are better than others. The New American Bible makes an attempt to translate the Scriptures into common American English, which is fine; but every once in a while you come across a subtlety in the original Greek or Hebrew which is lost in the attempt. Case in point: the opening verse of this passage we just heard, the Parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man. What we heard was that a rich man had a certain beggar "lying at his door." What it actually says, in fact, is “a certain beggar … ἐβέβλητο πρὸς τὸν πυλῶνα αὐτοῦ εἱλκωμένος (had been placed at his gate)”, the Pluperfect Passive of βάλλω, literally, "had been placed by being thrown"; which implies that this was not a chance encounter: the beggar didn’t just show up one day; he was put there deliberately for a specific purpose by someone who is not named, which, in the Bible, means it was God, which is evidenced by the fact that we are told the beggar's name; if the one telling us the story knows his name, it's because the one telling us the story put him there. So, the implication is that Lazarus was put there by God as a test, to force the Rich Man into making a moral decision, which, when you think about it, is crucial to understanding the meaning of the passage. 8:44 AM 9/25/2016 — The Roman Missal has its own translation of the Sacred Scriptures which follows very closely what is probably the most common translation of the Scriptures in use among Catholics in our country, called the New American Bible; and, it's unfortunate that we're not permitted to use other translations as is the case in other English speaking countries. As you know, there are a plethora of translations of the Bible into English; some are better than others. The New American Bible makes an attempt to translate the Scriptures into common American English, which is fine; but every once in a while you come across a subtlety in the original Greek or Hebrew which is lost in the attempt. Case in point: the opening verse of this passage we just heard, the Parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man. What we heard was that a rich man had a certain beggar "lying at his door." What it actually says, in fact, is “a certain beggar … ἐβέβλητο πρὸς τὸν πυλῶνα αὐτοῦ εἱλκωμένος (had been placed at his gate)”, the Pluperfect Passive of βάλλω, literally, "had been placed by being thrown"; which implies that this was not a chance encounter: the beggar didn’t just show up one day; he was put there deliberately for a specific purpose by someone who is not named, which, in the Bible, means it was God, which is evidenced by the fact that we are told the beggar's name; if the one telling us the story knows his name, it's because the one telling us the story put him there. So, the implication is that Lazarus was put there by God as a test, to force the Rich Man into making a moral decision, which, when you think about it, is crucial to understanding the meaning of the passage.

The rich man, like most rich people, has used his wealth to isolate himself from what is ugly in the world around him, as rich people often do. But it doesn’t work, because the beggar, Lazarus, is “laid at his gate,” as our Lord puts it. Which puts the rich man in an awkward position; because, now, in order to continue to isolate himself, he has to pretend that Lazarus isn’t there;—he has to literally step over him whenever he walks into his house—he has to ignore him, which he does, for which he ends up paying the penalty by being sent to hell.

Now, there are two points that are worth noticing here: first, the obvious fact that the rich man’s retribution, and consequently Lazarus’ reward, do not come in this life; they come in the next, when Lazarus is sent to heaven and the Rich Man goes to hell. It’s an important point to keep in mind, especially when we run into people who are having a hard time and who say, “I lived a good life; why is God letting this happen?” They are forgetting that reward and punishment do not happen here.

The Rich Man is very remorseful for how he’s lived and for ignoring the beggar at his gate, but by that time it’s too late: any opportunity he may have had to change his life is gone. And there occurs a very interesting—and sobering—exchange between them. The Rich Man, in the fires of hell, realizing that there’s now no way out of his predicament, asks Abraham to allow Lazarus to dip his finger in water and cool the Rich Man’s tongue. It’s an exact reversal of what was going on before they both died, when Lazarus was begging for a scrap from the Rich Man’s table. But it isn’t to be, as Abraham explains to the Rich Man that there is no communication between heaven and hell: Lazarus can’t reach across the gulf to cool the Rich Man’s tongue; the judgment made against him at the time of his death is final.

But what’s really remarkable—to me, anyway—is that, having had this explained to him, the Rich Man lapses into a fit of charity: in the midst of this unbearable torment, brought on, of course, by his own neglect, the Rich Man wants to spare his brothers, who are also rich, from the same fate. He asks Abraham to send Lazarus to them, so they can be warned to change their ways before it’s too late.  It seems—on the surface, anyway—to be an extremely magnanimous gesture, and it occurs to us, I think, that Abraham should look favorably on such a request. After all, it’s probably the first time in this Rich Man’s existence that he’s thought of the needs of others rather than his own. But Abraham rejects the idea. He tells the Rich Man that, even for his brothers, it’s too late. And the reason we should find that so sobering is because his brothers are not yet dead. Presumably they still have a chance to change their ways, but they are not to be permitted this warning. It seems—on the surface, anyway—to be an extremely magnanimous gesture, and it occurs to us, I think, that Abraham should look favorably on such a request. After all, it’s probably the first time in this Rich Man’s existence that he’s thought of the needs of others rather than his own. But Abraham rejects the idea. He tells the Rich Man that, even for his brothers, it’s too late. And the reason we should find that so sobering is because his brothers are not yet dead. Presumably they still have a chance to change their ways, but they are not to be permitted this warning.

It seems so unfair, but then Abraham explains why: they have Moses, they have the prophets, they have the Scriptures; they need nothing else. Everything they need to learn what they must do to be saved has already been provided. If they choose not to heed it, it is their own choice and their own fault.

Why, in our Lord's parable, were the writings of Moses and the Prophets not enough to teach these men how to live in order to be saved? Well, one reason may be because, even by our Lord’s time, the books of Moses and the Prophets in the Old Testament were already a thousand years old. Everyone was familiar with them—they were read regularly as part of the synagogue service—and maybe that was the problem. They had become ritualized. Just like the Gospel is for us. The Holy Gospel is read to us at every Mass, but how often do we pause to listen to what is being read, to hear what those words are trying to tell us? It’s not as if the Gospels are written in some kind of peculiar code which we need a theologian to decipher. Our Lord’s lessons in these parables are too often painfully clear. It’s just that we don’t listen. Just like the Rich Man didn’t listen, just like his bothers didn’t listen … until it was too late. And then we run the risk of having one of those head-slapping moments on the day of our own judgment wherein we say, “Oh, you mean I was supposed to actually apply that to my own life?! Who would have thought?”

There is a second point about this parable, as I said, to which I would draw your attention, and it’s a point that was made in the fifth century by Saint Cyril of Alexandria in his commentary on Luke’s gospel. He points out the fact that the Rich Man is never named by Jesus in the parable, He simply calls him “a Rich Man”; but the poor man, as we noticed already, He mentions by name. Why? Because the Rich Man, lacking in compassion and being totally unconcerned about the state of his soul, was nameless in God’s presence. And then he quotes Psalm 15, verse 4, in which God says, concerning those who do not fear Him, “I will not make mention of their names with My lips.” It’s a chilling statement about the harshness and finality of God’s judgment.

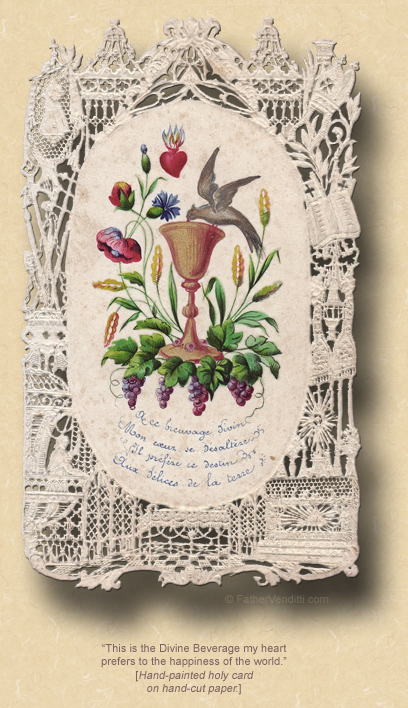

It is so easy for us, day after day, to come to church, sing the songs, say the prayers and go home to all the other “important” things that occupy our lives, having fulfilled whatever obligation we think we're fulfilling for another day or another week. And if we should resolve to ever make it more than that—and I think we all can agree that would be good—then that’s an adjustment that has to be made by each one of us in our own hearts. It’s not up the priest to inspire us, although if we have a priest that does that for us it’s helpful; but ultimately it’s up to each one of us to decide what we’re doing when we’re here: what we’re thinking about, what we’re praying about, whether we are truly listening to what’s being sung and said and examining our lives in light of it. No one is responsible for doing that for us. As Cardinal Newman once said, “I can no more think with thoughts not my own than I can breath with lungs not my own, nor can I pray [from a heart] not my own.” Everything that we need to be inspired and consoled, to be sanctified and saved has been provided to us by Christ through his Church. What we do with it is entirely up to us.

* Today is called "The First Sunday after the Holy Cross" because the previous Sunday, "The Sunday after the Exaltation," is considered part of the Postfestive period of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, and thus part of the feast itself. Following the feast and postfestive period of the Holy Cross (Sept. 14th through 21st), the Greek Church actually labels these Sundays as “Sundays after the Holy Cross” and begins to number them accordingly, calling today "The First Sunday after the Holy Cross," while the Ruthenian and Russian Churches continue to number them as "Sundays after Pentecost" (though in some older Ruthenian typicons the Greek custom is observed). The historical context of this custom was the Greek practice of marking the birthday of the Emperor Augustus on September 23rd, which they regarded as the first day of the Church year. It was not until the fall of the empire that the new year observance was moved to Sept. 1st throughout the Churches of the Byzantine Rite.

According to unsubstantiated legend, Euphrosyna (or Euphrosyne), the daughter of a very rich man, lived in Egypt in the fifth century. On the day of her wedding, she left her parents house secretly to avoid the marriage. With her hair cut short and dressed in man’s attire, she retired to a monastery where she lived a life of prayer and penance. There is no documentary evidence to prove this account of her life, or even if she actually existed.

Other Eastern Churches also commemorate on this day Saint Sergius of Radonezh, one of the most beloved saints of Russia, also born of a rich family, who devoted himself to the moral rebuilding of his people demoralized by Tartar hordes, and who is often regarded as the “Francis of Assisi” of the Russian Church. He died on this day in 1392. The typicon of the Ruthenian Church does not mention him.

** The four Gospels are all read in their entirety in the Byzantine Churches, and the reading of each begins with a great feast. The Gospel of St. John begins with the Feast of Feasts, Pascha, and is read until Pentecost. The Gospel of St. Matthew begins with Pentecost, and is read until the Feast of the Holy Cross, after which the Gospel of St. Luke is read all the way through until the Great Fast; but, because the Divine Liturgy is offered only on Saturday and Sunday in the Great Fast, the left-over passages are read in the last six weeks of the Matthean and Lucan cycles. This is why the Byzantine Churches begin the reading of Luke’s Gospel on the Sunday after the Holy Cross no matter where they are in the cycle of "Sundays after Pentecost." The Epistles, on the other hand, are read continuously without any adjustment, creating a discrepancy between Epistle and Gospel. Since Pascha was so early this year, it was necessary this year to repeat the Gospel of the 17th Sunday after Pentecost on the 18th Sunday; creating a discrepancy of one week until Dec. 28th. In the Byzantine Churches, this is commonly called "the Lucan Jump." Thus, today, the Epistle sung is the one for the Nineteenth Sunday, and the Gospel the one ordinary sung on the Eighteenth Sunday.

|