Fasten Your Seat Belts; We're Going for a Ride.

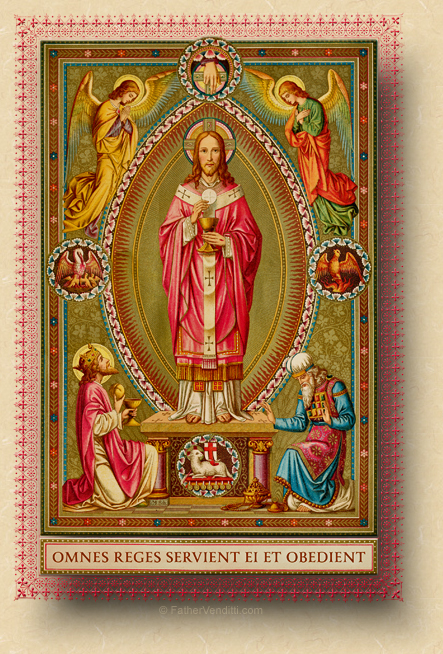

The Last Sunday of Ordinary Time: the Solemnity of Jesus Christ, King of the Universe.

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• II Samuel 5: 1-3.

• Psalm 122: 1-5.

• Colossians 1: 12-20.

• Luke 23: 35-43.

The Last Sunday after Pentecost.*

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Colossians 1: 9-14.

• Psalm 43: 8-9.

• Matthew 24: 15-35.

The Twenty-Seventh Sunday after Pentecost, the First of Philip's Fast; the Prefestive Day of the Entrance of the Theotokos; the Feast of Our Venerable Father Gregory the Decapolite; the Feast of Our Holy Father Proclus, Archbishop of Constantinople; and, the Feast of Our Blessed Mother Josaphata Hordashevska.**

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Ephesians 6: 10-17.

• Luke 12: 16-21.***

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:39 AM 11/20/2016 — The Solemnity of Christ the King has had a controversial history. When Pope Pius XI established the feast of Christ the King, he fixed its date for the last Sunday of October—the Sunday directly preceding the Feast of All Saints—and explained why in his encyclical. When Pope Blessed Paul VI moved the feast to the last Sunday of Ordinary Time, making its observance variable, he changed the spiritual thrust of the feast completely, and that decision remains controversial to this day. The Gospel lesson for the original feast harkens back to the original meaning of Christ the King as envisioned by Pius XI: all authority on earth is derived, directly or indirectly, from the authority of Christ, but that authority is spiritual, not political. The early followers of our Lord clearly saw Him as a political figure with religious overtones; they looked to him to lead some sort of revolution which would overthrow Roman rule and restore independence to Palestine, perhaps even restoring the old Kingdom of Israel. Of course, this was not our Lord's mission. This was considered a crucial message of consolation by Pius XI at a time when kingdoms were falling to the wave of nationalistic republicanism. The observance of the current feast seems to hover around a sort of anti-nationalistic spiritual globalism centered on justice and peace, sometimes mutating into a purely secular environmental agenda. 8:39 AM 11/20/2016 — The Solemnity of Christ the King has had a controversial history. When Pope Pius XI established the feast of Christ the King, he fixed its date for the last Sunday of October—the Sunday directly preceding the Feast of All Saints—and explained why in his encyclical. When Pope Blessed Paul VI moved the feast to the last Sunday of Ordinary Time, making its observance variable, he changed the spiritual thrust of the feast completely, and that decision remains controversial to this day. The Gospel lesson for the original feast harkens back to the original meaning of Christ the King as envisioned by Pius XI: all authority on earth is derived, directly or indirectly, from the authority of Christ, but that authority is spiritual, not political. The early followers of our Lord clearly saw Him as a political figure with religious overtones; they looked to him to lead some sort of revolution which would overthrow Roman rule and restore independence to Palestine, perhaps even restoring the old Kingdom of Israel. Of course, this was not our Lord's mission. This was considered a crucial message of consolation by Pius XI at a time when kingdoms were falling to the wave of nationalistic republicanism. The observance of the current feast seems to hover around a sort of anti-nationalistic spiritual globalism centered on justice and peace, sometimes mutating into a purely secular environmental agenda.

I choose to avoid the controversy by regarding this last Sunday of the Year of Grace as an epilogue to our liturgical journey over the past year, reflecting on the seamless flow of feasts and seasons, thus bringing the Year of Grace to a prayerful conclusion. So, let us proceed with that.

There are some films that you can watch over and over again and still see something that you didn't see before, and one of them—for me, anyway—is Gone with the Wind; not one of my favorite films, but still very interesting in many ways. And there's a scene toward the very beginning of the film that takes place during a party at Seven Oaks Plantation, filmed at an actual plantation I’ve been to outside Baton Rouge, where I had spent two summers as a seminarian working with Vietnamese refugees. And just as the scene is opening, the camera pans momentarily by a sundial—you have to look very quickly or else you'll miss it—and on the sundial are inscribed the words, “Never squander time; it is the stuff of which life is made.”

Today, as you know, the Jubilee Year of Mercy comes to an end, and the Holy Door, which we opened last December on the Feast of the Holy Family, will be closed toward the end of this Mass;  but, with it’s closure comes also the end of the Church’s Year of Grace; and, during these final weeks of the liturgical year, the Church has called us to consider the eternal truths of the Faith. We've already celebrated All Saints and All Souls, today is the Sunday of Christ the King which begins the last week of the Year of Grace; and, one week from today, we'll be launching into Advent which, despite everyone misunderstanding it, is focused not so much on preparing for Christmas as it is on preparing for the Second Coming of Christ and our final judgment; that's why it's a penitential season. but, with it’s closure comes also the end of the Church’s Year of Grace; and, during these final weeks of the liturgical year, the Church has called us to consider the eternal truths of the Faith. We've already celebrated All Saints and All Souls, today is the Sunday of Christ the King which begins the last week of the Year of Grace; and, one week from today, we'll be launching into Advent which, despite everyone misunderstanding it, is focused not so much on preparing for Christmas as it is on preparing for the Second Coming of Christ and our final judgment; that's why it's a penitential season.

So, it’s not just the Jubilee Year that ends today, the year of the Church comes to a close as well. Part of the genius of a Faith and a Church as ancient as ours is that it saw the psychological impact of presenting the thirty-three year life of our Lord on earth in one year, allowing us to re-live the life of Christ in and through the Church's liturgy; and, it was a great saint of the medieval Church, Saint Ignatius, the founder of the Jesuits and the master of meditation and mental prayer, who teaches us one of the most effective ways to read the Gospel: by picturing ourselves in the scene.

So, let's take this opportunity to think back to our Lord's birth, and picture ourselves traveling with the Holy Family to Bethlehem to report for the census, being turned away at the inn, finding the cave and watching Joseph fashion a cot for the Mother of God, witnessing the birth of our Lord, kneeling next to the Magi as they present their gifts. Once into January, we travel with the Holy Family to Jerusalem to witness the Circumcision of our Lord and; then, because of those mysterious missing years of our Lord's childhood, we suddenly find ourselves hiking down to the banks of the River Jordan where John, the son of our Blessed Mother's cousin, is preaching and baptizing and announcing the imminent arrival of our Lord in Judea, and will baptize Him. And we both see and hear the great announcement from heaven declaring Jesus the Divine Son of the eternal Father.

From that point on, events seem to move very quickly, almost too quickly for comfort; but, remember, we're compressing the life of our Lord into one year. John will get himself into trouble by his preaching and end up murdered, Jesus will begin to collect around Himself His own disciples and begin His preaching. He will perform a number of miracles and cures; then, almost as if there's a reel missing from the movie, all of a sudden we find ourselves in Lent, hearing our Blessed Lord warn about the evil of sin and the need to repent. We are reminded of the Prophesy of Isaiah which points to Jesus as the Christ, particularly the suffering of His passion and the redemption of mankind that it will bring.  We receive Holy Communion at the Last Supper, we weep with our Lord in the Garden, we stand outside the Prætorium with Peter and cringe as we hear him deny our Lord three times, then hear the cock crow. From the back of the crowd, our eyes follow our Blessed Lord as He carries the Blessed Cross, and we watch in horror as He is nailed to it. Then, when the holy women come and tell us that they've seen the risen Lord, we look at them like they're crazy … that is until we stand next to Thomas and put our own hands in the wounds, saying with that Holy Apostle, “My Lord and my God!” We receive Holy Communion at the Last Supper, we weep with our Lord in the Garden, we stand outside the Prætorium with Peter and cringe as we hear him deny our Lord three times, then hear the cock crow. From the back of the crowd, our eyes follow our Blessed Lord as He carries the Blessed Cross, and we watch in horror as He is nailed to it. Then, when the holy women come and tell us that they've seen the risen Lord, we look at them like they're crazy … that is until we stand next to Thomas and put our own hands in the wounds, saying with that Holy Apostle, “My Lord and my God!”

It's a very fast trip and, if one is not paying attention, one can miss it. It's a great shame, too, because most of us don't pay attention to it. We regard the selection of the readings and texts of the Mass as something that someone just sat down in some office and put together, not realizing that this plan of liturgical services crystallized in the first four hundred years after our Lord's Ascension as a result of the preaching and practice of the Apostles and their immediate successors whom we call the Fathers of the Church. But they didn't have a meeting about it and discuss, “How do we want to do this?” In most cases, they didn't even know one another. All of this developed as a result of the common experiences of the Christians of those early centuries as they sought to preserve the faith in circumstances of hardship and persecution which are alarmingly similar to what we face today.

Picture yourself in the year 300 somewhere in the Middle East, gathering on a Sunday to celebrate what was already called the Divine Liturgy, and which had already begun to look very much like what we do in church now. You're gathering in secret because your religion has been declared illegal; most of your friends and neighbors do not understand it, and would be shocked to find out that you're a part of it. You're in someone's home; or, if you're not in the Middle East but in Rome, you’re underground in a subterranean cemetery; or, if you're in Greece or thereabouts, you may be in an actual church built for that purpose, which was just beginning to happen in some places. The language would be Greek, or, if in Rome, Latin, or perhaps Aramaic if you were in Palestine or Jerusalem itself; but, everything else would be almost the same. There would be a reading from one of Saint Paul's letters, then an episode from the life of our Lord taken from one of the Gospels. The homily would focus on the life of our Lord, emphasizing His divinity, how His death and resurrection save us, and how we all must be courageous in the face of great temptation and difficulty. After the speech, gifts of bread and wine would be brought in, and the priest would pray for them to change into the Body and Blood of Christ.

It would take about six hundred years before the schema of the Church Year came to look like it does now, and it happened naturally: as Christians traveled from one part of the world to another, they informed one another of what each was doing in church; and, eventually, the Liturgies celebrated in the various churches around the world started to look more and more the same. Eventually, the Emperor would convert to the faith, and lend the force of the government to the spread of the Gospel. As crises would arise, the bishops of the Church would meet in council to discuss them and seek solutions; one of those councils composed the Creed and inserted it into the Liturgy, so that the basics of the Christian Faith would be proclaimed by every Christian on every Sunday, so that they would never forget them.

And so, here we are, so many centuries later, reliving the same journey of our Lord's life on earth through the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, traveling along with our Lord from His birth, through His baptism and early preaching, through His passion and death and finally His resurrection and return to His Father.  Every year we make this trip, just as our fathers did before us, and their fathers before them, and their fathers before them, for the last two thousand years. That's a long time to be doing the same thing over and over again. We do it now for the same reason that every Christian before us did it: we want to go to heaven, and the only way to get there is to follow our Lord, and live the way He taught us to live; and, we can't do that if we don't know our Lord. Every year we make this trip, just as our fathers did before us, and their fathers before them, and their fathers before them, for the last two thousand years. That's a long time to be doing the same thing over and over again. We do it now for the same reason that every Christian before us did it: we want to go to heaven, and the only way to get there is to follow our Lord, and live the way He taught us to live; and, we can't do that if we don't know our Lord.

What we do in church came to be because, over the course of time, it became clear that it was the most efficient way to keep our Lord's life and message alive, not to mention the fact that, as a sacrament, the Mass gives us our Lord's actual Body and Blood, without which our attempt to follow our Lord would be fruitless. It really would be a shame if we allowed the Liturgical Year to slip by without really paying attention to it, and considering the lessons it presents to us.

Now, the Gospel for this Sunday of Christ the King is taken from Luke this year, as were most of the Gospel lessons after Pentecost, and focuses on the true nature of Christ’s kingship by showing Him hanging on the cross and receiving the jeers of those who murdered Him as they mock Him, saying “So, this is the King of the Jews”; but, if it had been up to me—which is isn't—I would have chosen another lesson for this last Sunday of the Church's Year of Grace: it's also from Luke's Gospel, in which the evangelist records the first homily ever given by our Blessed Lord. Returning to His adopted home town of Nazareth, Jesus enters the synagogue, and is asked to read the portion of Scripture appropriate for that sabbath. He opens the scroll to chapter 61 of the Prophecy of Isaiah and reads: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me; he has anointed me, and sent me out to preach the gospel to the poor, to restore the broken-hearted; to bid the prisoners go free, and the blind have sight; to set the oppressed at liberty, to proclaim a year when men may find acceptance with the Lord, a day of retribution” (Luke 4: 18-19 Knox). And it would not be inappropriate for us—at least in this one sense—to allow our observance of a new Year of Grace to take a lesson from the secular observance of New Year's Day, and make for ourselves a Church Year resolution; for we are poor, probably materially, but certainly spiritually; we are prisoners of our egoism and our sins; we are all blind because our sins have blinded us to the beauty of the Divine Light, and are prisoners by attachment to the things of this world, and the pursuit of gratification in created things has left us brokenhearted.

When he had finished reading, our Lord told the congregation in the synagogue, “This scripture which I have read in your hearing is to-day fulfilled” (v. 21 Knox). Whether it's fulfilled in our hearing depends entirely on us. There is Jesus, offering us a new life. Today, on this last Sunday of the Year of Grace and this last day of the Jubilee Year of Mercy, this offer is made to us. And even if we have squandered it many times over the years, he renews the offer to us again; this year can still be for us a year of Grace with the Lord. We don't know if this will be the year we persevere; but at least, as a new Year of Grace approaches, we are offered another chance to try again.

Saint Luke says, “Then he shut the book, and gave it back to the attendant, and sat down. All those who were in the synagogue fixed their eyes on him” (v. 20 Knox). Perhaps that's enough for our Church Year resolution: that we will begin today to keep our eyes fixed on the Lord.

* The Mass for the Last Sunday after Pentecost is always taken from the Twenty-Fourth Sunday in the Missal. Because the date of Easter is variable, so are the number of Sundays from Pentecost until the First Sunday of Advent. If there are more than twenty-three Sundays, the texts for these Masses are taken from the Masses which were previously omitted after Epiphany, with the texts for the Twenty-Fourth Sunday reserved for this Last Sunday after Pentecost, which is always the Sunday before Advent. In this elegant way, the Missal provides for every Sunday in it to be celebrated at one time or another in the course of the year, and no Scripture lesson in the Missal is ever omitted.

** Philip's Fast, the season of penitential preparation for Christmas, so named because it begins on the day after the Feast of the Apostle Philip on the Byzantine Calendar, corresponds to the Roman Rite season of Advent, though it's origins are much later, dating no earlier than the thirteenth century. Lasting for six weeks rather than the four of Advent, what is required during this period varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. The traditional observance would be a strict abstinence from both meat and dairy products on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, with wine and oil allowed on Tuesdays and Thursdays; then, beginning on December 10th in some Churches and on December 20th in others, the strict abstinence becomes daily except on Saturdays and Sundays on which there is traditionally never a fast. The Particular Law of the Ruthenian Metropolia in the United States (Canon 880, § 2) recognizes Phillip's Fast as a penitential season, states the traditional observance, then requires that it be observed voluntarily according to one's individual ability … not unlike the observance in the Latin Church, in which nothing is specifically required.

Gregory, called "the Decapolite" because he was from there, was one of the defenders of the veneration of icons against those who regarded it as idolatry. He was the spritual director of the two venerable hymnographers, John and Joseph, and sent Joseph to Rome to bring Pope Gregory IV details about the persecution waged by Emperor Theophilos against those who venerated icons. He died in Constantinople on this day in 842.

Proclus, a disciple of St. John Chrysostom, was elevated to the See of Constantinople in 434 during the reign of Emperor Theodosius. He sent to the Church of Armenia a long exposition of the true faith, refuting the Nestorian heresy. He received the remains of John Chrysostom when they were solemnly transferred to the capital in 438, and died in 446.

As a teenager, Michaelina Hordashevska, of Lviv (now in Ukraine), attended several retreats given by a Byzantine Catholic congregation, the Basilian Fathers, inspiring her to enter religious life. At the age of eighteen, she entered a convent of contemplative Basilian nuns, then the only women's congregation of the Byzantine Rite. Recognizing the need for an active women's congregation, the Basilians assigned her the task of founding the Sisters Servants of Mary Immaculate to fill this need. In preparation, Sister Michaelina spent time with an active Roman Rite congregation, the Felician Sisters. She became mother superior of the Sisters Servants, taking the name Josaphata in honor of the Ukrainian martyr, Saint Josaphat. This congregation, with an active apostolate, later grew to become the largest institute of women religious for Byzantine Rite Ukrainian Catholics. Mother Josaphata exercised her zeal in teaching, nursing the sick, and visiting the needy, as well as in the promotion of Byzantine chant and the fitting adornment of churches. She died of bone cancer on April 7, 1919, and was beatified by Pope St. John Paul II in Lviv on June 27th, 2001.

*** In the Churches of the Byzantine Rite, the "Lucan Jump" is in effect for this and the following weeks through December 28th. This Gospel lesson is actually that for the 26th Sunday. Cf. the second footnote attached to the post here for an explanation.

|