God Grades on a Curve.

The Thirty-Third Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the primary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Proverbs 31: 10-13, 19-20, 30-31.

• Psalm 128: 1-5.

• I Thessalonians 5: 1-6.

• Matthew 25: 14-30.

The Sixth Remaining Sunday after Epiphany.*

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Thessalonians 1: 2-10.

• Psalm 101: 16-17.

• Matthew 13: 31-35.

The Twenty-Fourth Sunday after Pentecost (the Ninth after the Holy Cross & the First of Philip's Fast); the Feast of the Holy Prophet Obadiah; the Feast of the Holy Martyr Barlaam; and, the Feast of Our Holy Mother Marie-Alphonsine Ghattas.**

First & third lessons from the pentecostarion, second & fourth from the menaion for the Martyr, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Ephesians 2: 14-24.

• Colossians 1: 12-18.

• Luke 12: 16-21.***

• John 15: 17—16: 2

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:38 AM 11/19/2017 — There are some films that you can watch over and over again and still see something that you didn't see before, and one of them—for me, anyway—is Gone with the Wind; not one of my favorite films, but still very interesting in many ways. And there's a scene toward the very beginning of the film that takes place during a party at Seven Oaks Plantation, filmed at an actual plantation outside Baton Rouge that I visited once. And just as the scene is opening, the camera pans momentarily by a sundial—you have to look very quickly or else you'll miss it—and on the sundial are inscribed the words, “Never squander time; it is the stuff of which life is made.” 8:38 AM 11/19/2017 — There are some films that you can watch over and over again and still see something that you didn't see before, and one of them—for me, anyway—is Gone with the Wind; not one of my favorite films, but still very interesting in many ways. And there's a scene toward the very beginning of the film that takes place during a party at Seven Oaks Plantation, filmed at an actual plantation outside Baton Rouge that I visited once. And just as the scene is opening, the camera pans momentarily by a sundial—you have to look very quickly or else you'll miss it—and on the sundial are inscribed the words, “Never squander time; it is the stuff of which life is made.”

During these final weeks of the liturgical year, the Church calls us to consider the eternal truths of the Faith. We've already celebrated All Saints and All Souls, and before the month is out we'll be worshiping Christ the King and launching into Advent which, despite everyone misunderstanding it, is focused not so much on preparing for Christmas as it is on preparing for the Second Coming of Christ and our final judgment; that's why it's a penitential season. Even today, in our second lesson from Paul's first letter to the Thessalonians, we are warned that Christ will come “like a thief in the night” (5: 1-6). No matter how prepared we think we are for its arrival, death always takes us by surprise.

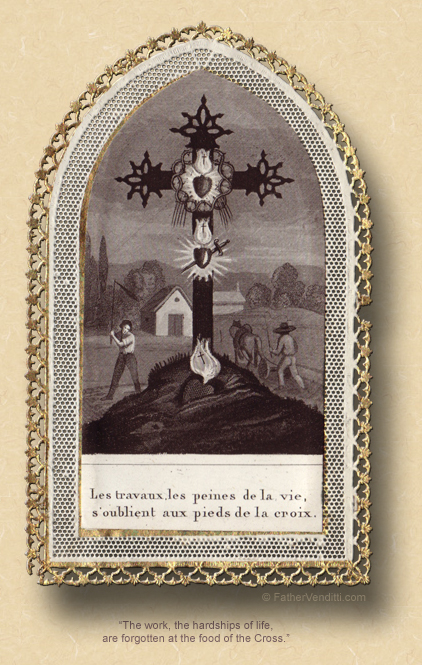

And I would like to recommend to you that this is the best way for us to consider today's Gospel lesson. The parable is about a man going on a trip and entrusting parts of his business to three different individuals, and each is given an amount of money commensurate with his abilities; and, if we looked at it superficially, we could make the mistake that it's just a lesson about being industrious and fastidious with responsibilities entrusted to us. But why would our Lord waste time giving a lesson on business administration, no matter how sage and wise it may be? When our Lord speaks, it's to teach us how to go to heaven, not how to make sound investments.

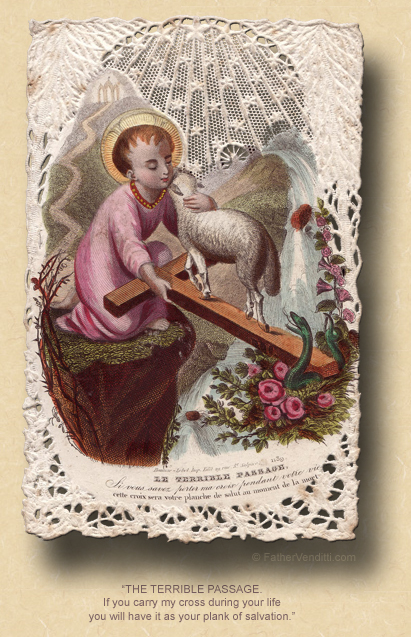

We are in this parable. Each of us is one of the three people to whom is entrusted some amount of money to care for in the master's absence. It's important to note that they don't all receive the same. That's because we are not all equal. To give each of us the same gifts and responsibilities would be unjust because we don't all have the same abilities. That's the meaning of our Lord's phrase, “To him who has much, much will be required.” And if you're one of those who find yourself constantly complaining, “Why, Lord, why? Why am I the one who has to carry this burden, to suffer this problem, to take care of this difficult person, and not someone else,” etc., etc., it's because someone else hasn't been given the grace to do it, and you have … maybe not without difficulty, maybe not without hardship, maybe not without a tremendous amount of sacrifice and suffering, but the grace to do it has been given to you. It's called the Dogma of Sufficient Grace, and the Church regards it as a Divinely revealed truth: God imposes no sacrifice upon us without the grace to see it through; but, understand that it's the Dogma of Sufficient Grace, not the Dogma of Abundant Grace.  The grace that's given to us is the Grace to carry the Cross, not the grace to waltz through life whistling show tunes without a care in the world. The grace that's given to us is the Grace to carry the Cross, not the grace to waltz through life whistling show tunes without a care in the world.

“Do not be surprised, beloved,” says Saint Peter in his First Epistle, “that this fiery ordeal should have befallen you, to test your quality; there is nothing strange in what is happening to you. Rather rejoice, when you share in some measure the sufferings of Christ; so joy will be yours, and triumph, when his glory is revealed” (I Peter 4: 12, 13 Knox). He's responding to those who react the way we so often do when suffering comes our way: we keep asking, “Why, Lord? Why?” And we've talked about this before. We keep saying in our prayers, “Lord, I've lived a good life. Why is this happening to me?” It's almost as if we've never read the Gospel. Christianity is the religion of the cross. The marvel would be if we were not suffering; that would be hard to explain.

That's why we are given sufficient grace and not abundant grace. If we were given abundant grace so that we could meet every responsibility life throws at us without so much as suffering a hangnail along the way, how could we possibly make up for our fallen nature and merit the Kingdom of Heaven? We are born, remember, into a state of Original Sin, and there are consequences to that. Our Lord made salvation possible for us through his own death on the Cross, but that by itself doesn't automatically make us all saints; we have to buy into that by carrying the Cross along with him.

These three guys in the parable who represent all of us: they're all given different amounts because their master knows them, just like God knows each of us. They are each given, as I said, amounts commensurate with their own individual abilities, just as God gives to us tasks and responsibilities according to the grace that he has already given us. For the most part, the fellows in the parable perform as expected: the guy who was judged able enough to handle five talents—I have no idea what the current exchange rate is for dollars to talents; it doesn't matter—performed exactly as expected, and returned five talents more. The next guy wasn't given quite as much because the master clearly thought he wouldn't have been able to handle it, and he was right; nevertheless, he did return a profit; not nearly as impressive as the guy before him, but he did apply himself and perform according to his ability. Notice that he gets the same praise—and we presume the same reward—as the first man, so the master is grading on a curve. So, clearly, the amount each returned was not what was important; that each one applied himself according to his ability and what he had been given … that's what was important.

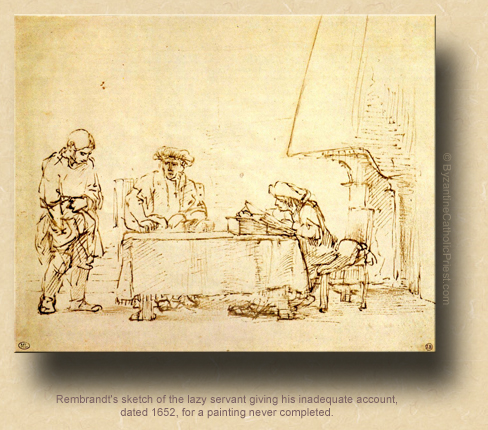

But now we come to this last sad sack. There's always one loser in the class who routinely upsets the curve. And, of course, he's failed even before he starts: “Then the one who had received the one talent came forward and said, 'Master, I knew you were a demanding person, harvesting where you did not plant and gathering where you did not scatter; so out of fear I went off and buried your talent in the ground. Here it is back.'” (Matt. 25: 24-25 NABRE). So, he didn't even try. We could, I suppose, analyze him and try to figure out why he didn't try; perhaps he was a proud individual, and was miffed that the master didn't consider him capable of more than one talent; maybe he was jealous that these other guys had been judged more capable than him, and he was offended. In any case, as it turns out, the master was giving him more credit than he was worth, because he couldn't even handle the one talent he was given.  And it's sad because, even if he had returned just one talent more, which would have been considerably less than the other two, he still would have performed according to the master's initial judgment of his ability, and would have received the same reward. But his envy and his jealousy overtake him, and he just folds, doing absolutely nothing, and becoming, in the process, absolutely worthless. And it's sad because, even if he had returned just one talent more, which would have been considerably less than the other two, he still would have performed according to the master's initial judgment of his ability, and would have received the same reward. But his envy and his jealousy overtake him, and he just folds, doing absolutely nothing, and becoming, in the process, absolutely worthless.

Which takes us back to the sundial at the beginning of Gone with the Wind. Believe or not, life is not a gift, even though we always like to say it is. In reality, life is something we have on loan from God for a while. One day, we will all have to give it back, along with a report on what we have done with it. To be sure, there are some people who will be able to say they did great things: walked on the moon, discovered a cure for cancer, won the Nobel Peace Prize, invented hair in a can; most of us are not going to be able to say that; but, maybe we can say, “I raised some children in the Faith,” or “I took care of my elderly mother,” or “I bore an illness or a hardship patiently and with prayer”; perhaps some of us will be able to say no more than, “I refused to give up on life. I had it rough, to be sure, and failed a lot of times, and committed a lot of sins along the way, but I never gave up and lost my faith or turned away from Christ and His Church.” Whether that will be enough depends on how accurate is our assessment of what God has given us according to our abilities and our use of the sufficient grace that goes along with it. If we've been honest with ourselves—and with Christ—we know he grades on a curve, and our salvation will be assured.

* Because the date of Easter is variable, so are the number of Sundays from Pentecost until the First Sunday of Advent; yet, the Roman Missal of the extraordinary form does not provide texts for Sundays beyond the Twenty-Third Sunday after Pentecost. Therefore, if there are more than twenty-three, the texts for these Masses are taken from the Masses which were previously omitted after Epiphany (with the exception of the Last Sunday after Pentecost, which is always the Sunday before Advent, and for which there are proper texts). In this elegant way, the Missal provides for every Sunday in it to be celebrated at one time or another in the course of the year.

** Following the feast and postfestive period of the Holy Cross (Sept. 14th through 21st), the Greek Church actually labels these Sundays as “Sundays after the Holy Cross” and begins to number them accordingly, while the Ruthenian and Russian Churches continue to number them as "Sundays after Pentecost" (though in some older Ruthenian typicons the Greek custom is observed). The historical context of this custom was the Greek practice of marking the birthday of the Emperor Augustus on September 23rd, which they regarded as the first day of the Church year. It was not until the fall of the empire that the new year observance was moved to Sept. 1st throughout the Churches of the Byzantine Rite.

Cf. the footnote in the post here for an explanation of Philip's Fast.

Obadiah lived in the sixth century before Christ.

Barlaam was martyred in Antioch, and is mentioned in the homilies of St. John Chrysostom.

Marie-Alphonsine Danil Ghattas (1843–1927) was a Palestinian nun who founded the Dominican Sisters of the Most Holy Rosary of Jerusalem (the Rosary Sisters), the first Palestinian congregation. She was beatified by Archbishop Angelo Amato on behalf of Pope Benedict XVI in 2009.

*** The four Gospels are all read in their entirety in the Byzantine Churches, and the reading of each begins with a great feast. The Gospel of St. John begins with Pascha, and is read until Pentecost. The Gospel of St. Matthew begins with Pentecost, and is read until the Feast of the Holy Cross, after which the Gospel of St. Luke is read all the way through until the Great Fast; but, because the Divine Liturgy is offered only on Saturday and Sunday in the Great Fast, the left-over passages are read in the last six weeks of the Matthean and Lucan cycles. This is why the Byzantine Churches begin the reading of Luke’s Gospel on the Sunday after the Holy Cross no matter where they are in the cycle of "Sundays after Pentecost." The Epistles, on the other hand, are read continuously without any adjustment, creating a discrepancy between Epistle and Gospel. This year, there is a discrepancy of two weeks. In the Byzantine Churches, this is commonly called "the Lucan Jump." Thus, today, the Epistle sung is the one for the current Sunday after Pentecost, and the Gospel the one ordinary sung two week's hence.

|