Humility a Function of Maturity.

The Thirty-Second Wednesday of Ordinary Time; or, the Memorial of Saint Albert the Great, Bishop & Doctor of the Church.

Lessons from the primary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Wisdom 6: 1-11.

• Psalm 82: 3-4, 6-7.

• Luke 17: 11-19.

|

When a Mass for the memorial is taken, lessons from the feria as above, or from the proper:

• Sirach 15: 1-6.

• Psalm 119: 9-14.

• Matthew 13: 47-52.

…or, any lessons from the common of Pastors for a Bishop, or the common of Doctors of the Church..

|

The Third Class Feast of Saint Albert the Great, Bishop, Confessor & Doctor of the Church.

Lessons from the common "In médio…" of a Doctor of the Church, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• II Timothy 4: 1-8.

• Psalm 36: 30-31.

• Matthew 5: 13-19.

The First Day of Philip's Fast; and, the Feast of the Holy Martyrs & Confessors Gurias, Samonas & Habib.*

First & third lessons from the pentecostarion, second & fourth from the menaion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• I Timothy 4: 1-12.

• Ephesians 6: 10-17.

• Luke 15: 1-10.

• Luke 12: 8-12.

FatherVenditti.com

|

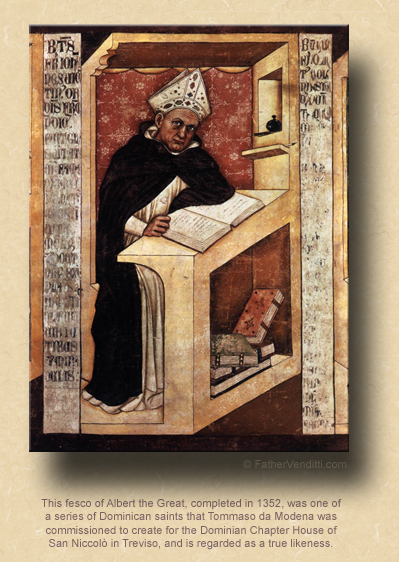

9:40 AM 11/15/2017 — Albert the Great is rightly named. Rarely do we find, even among the saints, a man in whom holiness of life and intellectual power exist side by side. Allow me to read to you the brief biography of him from the Roman Breviary: 9:40 AM 11/15/2017 — Albert the Great is rightly named. Rarely do we find, even among the saints, a man in whom holiness of life and intellectual power exist side by side. Allow me to read to you the brief biography of him from the Roman Breviary:

Albert, called the Great, because of his unusual learning, was born at Lauingen on the Danube in Swabia and carefully educated from his boyhood. He left his country to study in Padua. While he was there he applied to enter to the Dominicans. His uncle protested futilely against this step, but Blessed Jordan, master general of the Order of Preachers, encouraged it. When Albert had joined the friars, he was a shining example of religious observance and devotion. He loved the Blessed Virgin Mary above all and burned with zeal for souls. To complete his studies he was sent to Cologne. Then he was made professor at Hildesheim, at Freiburg and Ratisbon and at Strasbourg. In the master's chair at Paris, he earned a high reputation. He had Thomas Aquinas for his beloved disciple and was the first to perceive and predict the loftiness of his intellect. At Anagni, in the presence of the Pope Alexander IV, he refuted William, who had wickedly attacked the mendicant orders. Later he was made bishop of Ratisbon, where, in giving counsel and in settling disputes, he worked such wonders as to deserve the title of peacemaker. He wrote many things about almost all branches of learning, especially the sacred sciences, and composed some famous works about the wonderful Sacrament of the altar. Famous for his virtues and for his miracles, he died in the Lord in the year 1280. By the authority of the pope a cult had long since been granted him in many dioceses and in the Order of Preachers; and, when Pius XI, willingly acceding to the desire of the Sacred Congregation of Rites, extended his feast to the whole Church, he gave him also the title of Doctor of the Church. Pius XII appointed him the heavenly patron with God of all those who study the natural sciences.

Now, turning our attention to today’s Gospel lesson:

Of course the Gospel today focuses on the virtue of gratitude. We’d probably all agree that gratitude is a rare enough quality when it comes to how we deal with one another; but, it’s just as rare, if not more so, in our dealings with God. And today we are presented that incident when our Lord encountered ten lepers and cured them all, but only one came back to give thanks. And our Lord even asked him, “Were not all ten made clean? And the other nine, where are they?” And I don’t wonder if that ratio isn’t accurate. We are grateful for maybe a tenth of what we should be grateful for.

It’s easy to focus on what’s wrong with our lives, and everyone has something wrong. There’s no one who wouldn’t say that there isn’t something in his or her life that he wouldn’t want to change somehow.  For some it may be something trivial; for others it may be something monumental, like a marriage that’s gone bad, or a child that’s in trouble, or a serious health problem. There’s always something negative that we can think about. And when there’s something wrong, it’s very difficult to put that aside and say, “Yeah, but look what’s right with my life. Look at how fortunate I am aside from this problem.” There’s always something to get depressed about if what you want is to be depressed. For some it may be something trivial; for others it may be something monumental, like a marriage that’s gone bad, or a child that’s in trouble, or a serious health problem. There’s always something negative that we can think about. And when there’s something wrong, it’s very difficult to put that aside and say, “Yeah, but look what’s right with my life. Look at how fortunate I am aside from this problem.” There’s always something to get depressed about if what you want is to be depressed.

A couple of times you've heard me speak about what we call Spiritual Maturity. A spiritually mature person is one who can receive the crosses given to him in life, not necessarily without hardship, not without difficulty or suffering, not even without complaining sometimes, but without any effect on the strength of his faith. It is said that the first sign of maturity in a child is when he first realizes that mom and dad know better, not because he’s seen the reason of his parents’ position, but because he understands that they are more experienced than he, and therefore understand things that he can’t yet. And that same thing is true in our relationship with God: we can say we are spiritually mature when we can realize that God’s ways are not our ways; and that it isn’t necessary to understand why this or that has happened, except to understand that God has a handle on it even if we don’t. It takes a lot of humility to reach that point in life; but humility is also a function of maturity.

About a week from now our nation will observe that annual day of prayer—at least originally it was supposed to be a day of prayer—which we call Thanksgiving Day, and not long after that begins the penitential season of Advent; so, here’s a question you can add to your examination of conscience for both occasions: am I grateful for everything I have received, or do I choose, instead, to brood about what I think has been denied to me?

* Gurias and Samonas, priests of Edessa, were martyred under Emperor Diocetian. Habib, a deacon, was martyred under Emperor Lycinius.

Philip's Fast, the season of penitential preparation for Christmas, so named because it begins on the day after the Feast of the Apostle Philip on the Byzantine Calendar, corresponds to the Roman Rite season of Advent, though it's origins are much later, dating no earlier than the thirteenth century. Lasting for six weeks rather than the four of Advent, what is required during this period varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. The traditional observance would be a strict abstinence from both meat and dairy products on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, with wine and oil allowed on Tuesdays and Thursdays; then, beginning on December 10th in some Churches and on December 20th in others, the strict abstinence becomes daily except on Saturdays and Sundays on which there is traditionally never a fast. The Particular Law of the Ruthenian Metropolia in the United States (Canon 880, § 2) recognizes Phillip's Fast as a penitential season, states the traditional observance, then requires that it be observed voluntarily according to one's individual ability … not unlike the observance in the Latin Church, in which nothing is specifically required.

|