Silence is Not Always Golden.

The Memorial of Our Lady of the Rosary.

Lessons from the secondary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Galatians 3: 7-14.

• Pslam 111: 1-6.

• Luke 11: 15-26.

|

…or, from the proper:

• Acts 1: 12-14.

• [Responsorial] Luke 1: 46-55.

• Luke 1: 26-38.

…or, any lessons from the common of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

|

The Second Class Feast of Our Lady of the Holy Rosary; and, the Commemoration of Saint Mark, Pope & Confessor.*

Lessons from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Proverbs 8: 22-24, 32-35.

• Psalm 44: 5, 11-12.

• Luke 1: 26-38.

|

If the Mass for the feast is a High Mass, and a Low Mass for the commemoration is taken**, lessons from the common "Si díligis me…" of One or Several Holy Popes:

• I Peter 5: 1-4, 10-11.

• Psalm 106: 32, 31.

• Matthew 16: 13-19.

|

The Twentieth Friday after Pentecost; and, the Feast of the Holy Martyrs Sergius & Bacchus.***

First & third lessons from the pentecostarion, second & fourth for the menaion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Colossians 2: 1-7.

• Hebrews 11: 33-40.

• Luke 7: 31-35.†

• Luke 21: 12-19.

FatherVenditti.com

|

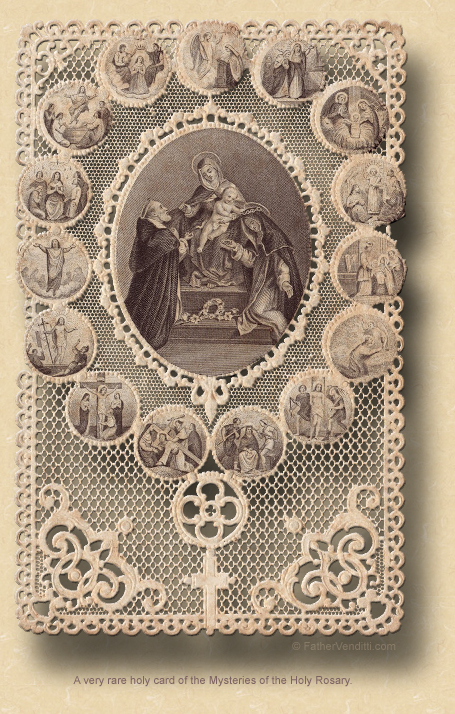

10:21 AM 10/7/2016 — Saint Dominic did not invent the Rosary, nor was it revealed to him by any kind of vision or message from the Mother of God, any holy card you may have in your prayer book depicting that fictional event notwithstanding. You’d be surprised how many people give me sour looks whenever I say that. The Dominicans had a lot to do with popularizing the Holy Rosary, as they latched onto it as a useful tool in combating the many Christological heresies that plagued the Church at the time of their foundation; but, most historians trace the Rosary's origin to 9th century Ireland. Then, as now, the liturgical life of monasteries centered around the Divine Office, most of which consists of the chanting of the 150 Psalms. Lay people living near the monastery saw the beauty of this form of prayer; but, because very few people outside the monasteries could read, lay people had to find a way to adapt this prayer for their own use. By the year 800, it was common practice in Ireland to recite 150 Our Fathers in place of the 150 psalms. 10:21 AM 10/7/2016 — Saint Dominic did not invent the Rosary, nor was it revealed to him by any kind of vision or message from the Mother of God, any holy card you may have in your prayer book depicting that fictional event notwithstanding. You’d be surprised how many people give me sour looks whenever I say that. The Dominicans had a lot to do with popularizing the Holy Rosary, as they latched onto it as a useful tool in combating the many Christological heresies that plagued the Church at the time of their foundation; but, most historians trace the Rosary's origin to 9th century Ireland. Then, as now, the liturgical life of monasteries centered around the Divine Office, most of which consists of the chanting of the 150 Psalms. Lay people living near the monastery saw the beauty of this form of prayer; but, because very few people outside the monasteries could read, lay people had to find a way to adapt this prayer for their own use. By the year 800, it was common practice in Ireland to recite 150 Our Fathers in place of the 150 psalms.

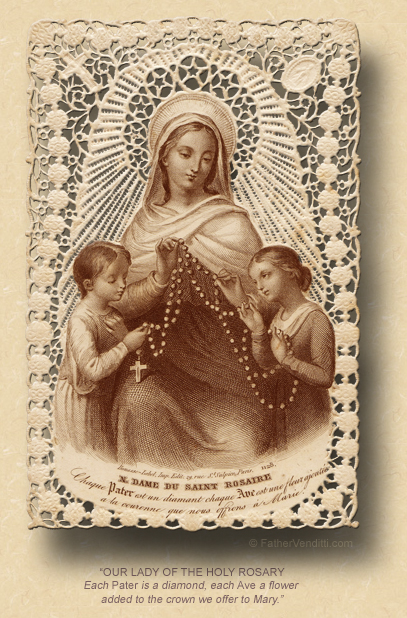

Yesterday, on the Memorial of Saint Bruno, I told you about the community he founded in the 10th century, the Carthusians, and my experience with them. It was a Carthusian monk, Henry of Kalkar, in 1365, who first suggested the practice of reciting 150 Hail Marys in groups of ten, separated by an Our Father. Another monk of the same community, Dominic the Prussian, in 1409, wrote a book which attached thoughts for mediation on the lives of our Lord and our Lady to each group, thus creating what we call today the Mysteries of the Rosary. It wasn’t really until then that the Dominicans entered the picture, and it was left to the Dominican friar, Alan of Rupe, to popularize devotion to the Rosary as a means of meditation throughout the world.

The addition of an additional set of five mysteries to the Rosary by Pope Saint John Paul II—recitation of which he said was purely optional—had the unfortunate effect of blurring the link of the Holy Rosary to the Psalter, as it would no longer correspond to the 150 Psalms; and, in his 2002 Apostolic Letter, Rosarium Virginis Mariæ, in which he first introduces us to the Mysteries of Light, he mentions that, while the Rosary has it's origin in the Psalter, it has long taken on a life of its own, and is now much more than a simple replacement for praying the Psalms. Indeed, in this day and age, in which most people can read, those who wish to pray the Psalms can do so without having recourse to a replacement.

Thus, the genesis and development of the Holy Rosary in the life of the Church is a beautiful example of how the love of the faithful for our Lord and our Lady can blossom into an integral part of the life of the whole Church; and, now we could hardly imagine ourselves without it. The fact that the Mother of God Herself, at Fatima, requested that we meditate on the Mysteries of the Rosary as part of our Five First Saturdays observance shows how even the Heavenly Church responds to the Church Militant, just as our Lord said: “…whatever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound in heaven; and whatever thou shalt loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven” (Matt. 16: 19 Knox).

The Memorial of Our Lady of the Rosary, which we celebrate today, was originally established as a second class feast by Pope Saint Pius V locally in Rome in thanksgiving for the decisive defeat of the Turks at the battle of Lepanto in 1571,  and was extended to the Universal Church in thanksgiving for their subsequent defeat at the battle of Belgrade in 1716; and, in the extraordinary form, it is still observed as a feast of the second class. and was extended to the Universal Church in thanksgiving for their subsequent defeat at the battle of Belgrade in 1716; and, in the extraordinary form, it is still observed as a feast of the second class.

But today is also First Friday which, as you know, we observe here at the Shrine with a Eucharistic Holy Hour following Holy Mass. Since I’ve been here, we’ve usually begun our Holy Hour on First Friday by reciting together the Litany of the Sacred Heart; but, because of today’s memorial, we’ll be replacing that with the Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary. In fact, we used to recite that litany—or the Litany of the Immaculate Heart—on every First Saturday at the beginning of a Holy Hour, but that was pushed aside by our current First Saturday program. It probably never occurred to anyone that, now, we don’t have any occasion here at the Shrine where the Litany of the Blessed Virgin is recited regularly, which is kind of disconcerting. When we say the Rosary here at the Shrine, we always conclude it with the Salve Regina, the “Hail, Holy Queen,” but when I was a child we were taught to conclude the Rosary with the Litany of the Blessed Virgin; and, when I go on retreat with other priests toward the end of this month, we will conclude the daily Rosary, as we do every year, with the Litany because that’s how we were trained.

By the way, the Holy Hour today will conclude with Benediction at 1:30 regardless of when this Mass ends, so that you can plan the rest of your day accordingly. And so, without further adieu, it is now time to turn our attention to today’s Gospel lesson. I’ll bet you thought it was over, didn’t you? You should be so lucky.

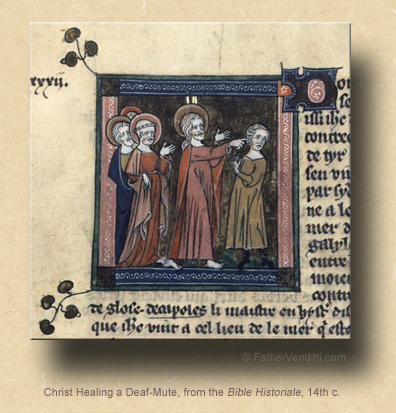

For some peculiar reason, today's Gospel lesson enters a narrative midstream. At the request of His disciples, our Lord had just driven out a demon from a man who was mute, which causes some consternation among some of those who had witnessed it, arising to the accusation that He's in league with the devil. Part of the problem rests with how the Jews of our Lord's time viewed sickness and handicap: a person was physically afflicted because of God's displeasure, which is a foreign concept to us, but very common in a superstitious time like that in which our Lord was on earth as a man. And, while the Roman Missal seems to want us to focus on the devil as a subject of today's Mass, I choose to take a different approach.

In the Semitic culture of Palestine, a person was blind or deaf or lame or, in the case of the man just cured leading up to today's Gospel lesson, mute because he had sinned or, if he was born that way, because of a sin inherited from his parents. Remember, when our Lord encountered the man born blind, His own disciples asked him, "Rabbi, who has sinned, this man or his parents, that he should be born blind?" (John 9: 2 Douay-Rheims). And the cures that Jesus brings about on these occasions, in addition to simply being done to help someone in need, are most definitely intended by our Lord to represent the spiritual healing that He comes to effect in our lives.

Keeping this clearly in mind as we read the Holy Gospels, we cannot help but notice that, in the way Jesus acts toward the sick, He is giving us an image of the sacraments. Saint John Chrysostom, commenting on today's Gospel lesson, tells us that this man “was unable to present his request himself, because he was dumb; he was unable to ask others to do it either, because the devil had tied his tongue, and together with his tongue he had bound up his soul” (Homilies on the Gospels, 32, 1).

How many times have we left the confessional only to remember later that there was something we needed to say to our Lord, but had forgotten to say it? More common, perhaps, is the phenomenon rooted as much in psychology as in spirituality, wherein someone will go to confession with every intention of making a clean breast of everything, but simply can't get it out: maybe they're embarrassed;  maybe the sin occurred in the midst of some traumatic experience that the individual finds difficult to relive; maybe it's just been so many years since someone confessed that he's afraid of what the priest will say, forgetting that he's not telling his sins to the priest, he's telling them to Christ. Priests I know who work in the Marriage Tribunal of our diocese tell me that one of the reasons petitions for decrees of nullity often take so long to process and bring to judgment is not because of some kind of slowness on the part of the Tribunal, but because the petitioner often takes a long time to collect the necessary information, because part of the process requires them to put down on paper, in excruciating detail, all the horrors that brought about the dissolution of the marriage, and people have a hard time plowing through the emotions required to do that; no one wants to relive the most heart-breaking part of his or her life. maybe the sin occurred in the midst of some traumatic experience that the individual finds difficult to relive; maybe it's just been so many years since someone confessed that he's afraid of what the priest will say, forgetting that he's not telling his sins to the priest, he's telling them to Christ. Priests I know who work in the Marriage Tribunal of our diocese tell me that one of the reasons petitions for decrees of nullity often take so long to process and bring to judgment is not because of some kind of slowness on the part of the Tribunal, but because the petitioner often takes a long time to collect the necessary information, because part of the process requires them to put down on paper, in excruciating detail, all the horrors that brought about the dissolution of the marriage, and people have a hard time plowing through the emotions required to do that; no one wants to relive the most heart-breaking part of his or her life.

In the Divine Office, every morning the priest prays what's called the Invatatory Psalm, which is Psalm 95:

Oh, that today you would hear his voice: “Harden not your hearts as at Maribah, as in the day of Massah in the desert, Where your fathers tempted me; they tested me though they had seen my works” (Psalm 95: 8-9 NABRE).

The historical reference, of course, is to events recorded in Exodus 17 (cf. v. 7); but, applying it to the context of today's Mass, it refers not to a hardening of one's heart as a result of obstinacy; it's a hardness brought about by a lacking in the virtues of Faith and Hope: we either doubt the Truth of the Faith, that Christ can and does forgive our sins in confession, or we presume against our Lord's infinite mercy and doubt our Lord's desire to do so. And here is where the Devil comes into play, and why so much is said about him in today's lesson, and why he has caused a man to become mute: the result of this fear and presumption is silence, preventing us from going into the confessional at all, or, once we're in there, preventing us from speaking what needs to be spoken. This, of course, serves the Devil's purpose, because a sin not confessed is a sin not forgiven.

Now, it is a fact that, if our emotional state is such that we fail to speak a sin in confession because we simply can't muster the courage to do it, our Lord, who knows all our sins from the get-go, makes up for that handicap and forgives the sin anyway, which is why it's not necessary to run back to confession the next day or the next hour to try it again; it's simply sufficient, the next time one goes to confession, to mention what happened. And it doesn't matter how long it's been, or how terrible we think the sin may be.

“Gird yourselves and weep, O priests! wail, O ministers of the altar! Come, spend the night in sackcloth, O ministers of my God!” (Joel 1: 13 RM3), from the Book of the Prophet Joel; not a bad prayer for any priest about to enter the confessional to hear confessions. An even better prayer for the penitent going in to confess his sins would be Psalm 9: “The Lord rules forever, has set up his throne for judgment. It is he who judges the world with justice, who judges the peoples with fairness” (Psalm 9: 8-9 NABRE).

Which is all nothing more than an underhanded way of letting you know that, after we’ve exposed the Blessed Sacrament and I’ve cleaned up things after Holy Mass, I’ll return to the confessional. After the recitation of the Litany, the rest of the Holy Hour will be yours to converse with our Blessed Lord. As I said before, Benediction will be given at 1:30, and our services today will end with that.

* Pope St. Mark, the successor of St. Sylvester, occupied the Holy See for a few months, and died in the year 336.

** In the extraordinary form, when a commemoration falls on a second class feast, and the Mass for the feast is a High Mass, a subsequent Low Mass for the commemoration may be taken, provided there is a genuine need for a second Mass. In this case, no mention of the commemoration is made at the High Mass.

If, on the other hand, there is no High Mass this day, and the Mass or Masses for the feast are all Low Masses (as would be the case in most parishes), then a Mass for the commemoration is not permitted, and the commemoration is made by an additional Collect, Secret and Postcommunion added to those of the feast.

*** Sergius and Bacchus were captains in the Roman army, and where martyred under Emperor Maximianus Galerius around the year 297. They were held in high favor by the Emperor until they were exposed as secret Christians. They were then severely punished, with Bacchus dying during torture, and Sergius eventually beheaded. However, due to its historical anachronisms, the hagiography is considered ahistorical by many scholars.

† In the Churches of the Byzantine Rite, the "Lucan Jump" is in effect for this and the following weeks through December 28th. Cf. the footnote attached to the post here for an explanation.

|