Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, Who's the Fairest One of All?*

The Thirtieth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Sirach 35: 12-14, 16-18.

• Psalm 34: 2-3, 17-19, 23.

• II Timothy 4: 6-8, 16-18.

• Luke 18: 9-14.

The Twenty-Third Sunday after Pentecost.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Philippians 3: 17-21; 4: 1-3.

• Psalm 43: 8-9.

• Matthew 9: 18-26.

The Twenty-Third Sunday after Pentecost; and, the Feast of the Holy Apostle James, the Brother of God.

First & third lessons from the pentecostarion, second & fourth from the menaion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Ephesians 2: 4-10.

• Galatians 1: 11-19.

• Luke 16: 19-31.*

• Matthew 13: 54-58.

FatherVenditti.com

|

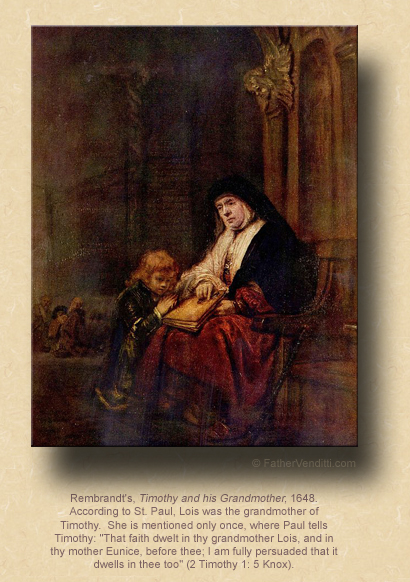

8:49 AM 10/23/2016 — Today’s second lesson, from the Blessed Apostle Paul’s Second Letter to Timothy, is quite heart-wrenching when you consider the background of it. Both of the Apostle’s letters to Timothy have to be read in conjunction with his letter to the Ephesians to really understand them. Timothy was a close friend of Paul's who had traveled with the Apostle on his first missionary journey and had even been arrested with him, so they were old cell mates. When Paul established the Church in Ephesus, he made Timothy the bishop there; but, Timothy was very young, perhaps too young to have been made a bishop, and the people there rejected him; so, Paul wrote to the Ephesians to set them straight about their duty to obey their bishop, and he wrote two personal letters to his friend to encourage him. These are, in fact, his last letters; he's under arrest again when he writes them. He writes them in transit as he's being taken to Rome to be tried for treason, so he knows that he will soon be dead, and the subject of his own eternal judgment is on his mind. 8:49 AM 10/23/2016 — Today’s second lesson, from the Blessed Apostle Paul’s Second Letter to Timothy, is quite heart-wrenching when you consider the background of it. Both of the Apostle’s letters to Timothy have to be read in conjunction with his letter to the Ephesians to really understand them. Timothy was a close friend of Paul's who had traveled with the Apostle on his first missionary journey and had even been arrested with him, so they were old cell mates. When Paul established the Church in Ephesus, he made Timothy the bishop there; but, Timothy was very young, perhaps too young to have been made a bishop, and the people there rejected him; so, Paul wrote to the Ephesians to set them straight about their duty to obey their bishop, and he wrote two personal letters to his friend to encourage him. These are, in fact, his last letters; he's under arrest again when he writes them. He writes them in transit as he's being taken to Rome to be tried for treason, so he knows that he will soon be dead, and the subject of his own eternal judgment is on his mind.

His advice to Timothy in the second letter addressed to him is practical enough, encouraging him to plod along with his priestly duties and embrace his suffering as participation in Christ's, but it causes him to reflect on his own imminent death, and I'll give you Msgr. Knox's translation because it is so clear and expressive, beginning with one verse before where today’s lesson begins:

It is for thee to be on the watch, to accept every hardship, to employ thyself in preaching the gospel, and perform every duty of thy office, keeping a sober mind. As for me, my blood already flows in sacrifice; the time has nearly come when I can go free. I have fought the good fight; I have finished the race; I have redeemed my pledge; I look forward to the prize that is waiting for me, the prize I have earned. The Lord, the judge whose award never goes amiss, will grant it to me when that day comes; to me, yes, and all those who have learned to welcome his appearing (2 Tim. 4: 5-8 Knox).

He’s knows he’s about to die;—it’s the quintessential near-death experience—and, that kind of near-death experience often becomes a kind of moral leveler: all of a sudden all of the rationalizations one has used throughout his life to justify his failings fall away, and one sees oneself as he is. That’s why people who know they are near to death will seek out the Sacrament of Confession, even if they’ve neglected it for many years. The ideal, of course, would be to cast off those rationalizations and seek the mercy of the Lord without being near to death.

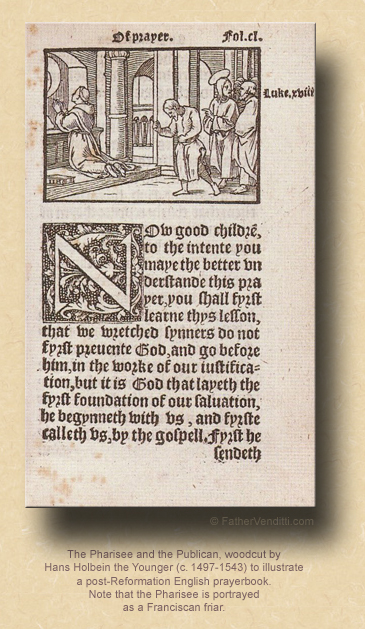

In the parable our Lord tells us in today’s Gospel lesson, neither the publican nor the pharisee are said to be near death, but the contrasting examples each offers us are prescient nonetheless, because one of them, for whatever reason, has come to see himself as he is, while the other only sees what he wants to see; and, while the parable seems simple enough on its face, there’s a subtext in between the lines which  exposes a gray area with regard to identifying the good and the evil as illustrated by the two examples our Lord presents to us, and it’s announced in the very first sentence of our Lord’s story: “Two men went up into the temple to pray…” (Luke 18: 10 Knox). Evil people don’t go to church. There’s the complicating rub: the Pharisee, who’s clearly the one whose example we’re not meant to follow, is not a bad man; if he had been, he wouldn’t be going to the Temple to pray. exposes a gray area with regard to identifying the good and the evil as illustrated by the two examples our Lord presents to us, and it’s announced in the very first sentence of our Lord’s story: “Two men went up into the temple to pray…” (Luke 18: 10 Knox). Evil people don’t go to church. There’s the complicating rub: the Pharisee, who’s clearly the one whose example we’re not meant to follow, is not a bad man; if he had been, he wouldn’t be going to the Temple to pray.

Now, the other fellow, whose example we clearly are meant to follow, is just as complicated. In the translation found in the Roman Missal, which we just heard, the words used to describe him are “tax collector,” like someone who works for the IRS. His title in Saint Luke’s Greek text is ὁ ἕτερος τελώνης, which does literally translate as “one who collects taxes,” but was often used much more broadly in conversation, which is why Msgr. Knox translates it as “publican,” meaning any kind of government official. And lest you think it’s an extraneous point, people in our Lord’s day were no different from people today—especially today, given how every poll you hear about shows how little the average American trusts his government. But, like the Pharisee, this man is also a devout Jew, as evidenced by the fact that he, also, is going into the Temple to pray. Compounding the complication is that the government he works for isn’t a Jewish government, it’s the Roman Empire. He’s collecting taxes from his own people and turning it over to an occupying enemy; and his payment is to skim a percentage off the top, so the more he collects the more he makes for himself, which means that, in the eyes of his fellow countrymen, he’s not just a nasty man from the IRS, he’s a traitor.

So, from the outset, in just one single sentence at the start of his story, our Lord challenges us to think outside the box. The Pharisee is a professional religionist, his passion is the study of the Scriptures, and his very life is dedicated to the love and worship of God; and the Publican, albeit a Jew who prays, lives a life—at least in public—far removed from love of God and country.

There is one thing, however, they both have in common, and it’s the one element not mentioned explicitly by our Lord, but written in between the lines: they’re both sinners; and that is what is most important to remember about them: both of them are sinners, but only one of them admits it. And our Lord points out that the tax collector who admitted he was a sinner left the temple a happier man. Why? Because he was honest. He had the courage and humility to see himself as he is. The Pharisee, on the other hand, instead of telling God his sins, tells God what a wonderful guy he is, how much he gives to the temple, how much he fasted, how much he prayed, etc. And Jesus says that this was not pleasing to God, not because these are not good things to do—because they obviously are—but because he didn’t tell the whole truth. He didn’t tell God his sins.  It’s in Matthew’s Gospel that our Lord mostly speaks directly to the Pharisees, and at one point he scolds them saying, “Woe upon you, scribes and Pharisees, you hypocrites that are like whitened sepulchres…” (Matt. 23: 27 Knox). What’s a sepulcher? It’s where you put dead people. They’re all white and clean on the outside, but what’s inside? Listen to the whole passage: It’s in Matthew’s Gospel that our Lord mostly speaks directly to the Pharisees, and at one point he scolds them saying, “Woe upon you, scribes and Pharisees, you hypocrites that are like whitened sepulchres…” (Matt. 23: 27 Knox). What’s a sepulcher? It’s where you put dead people. They’re all white and clean on the outside, but what’s inside? Listen to the whole passage:

Woe upon you, scribes and Pharisees, you hypocrites that are like whitened sepulchres, fair in outward show, when they are full of dead men’s bones and all manner of corruption within; you too seem exact over your duties, outwardly, to men’s eyes, while there is nothing within but hypocrisy and iniquity (vs. 27-28 Knox).

That’s a pretty stinging rebuke, especially when you consider that, inside a tomb where bodies are decomposing, it smells pretty bad. What he’s telling them is that, while outwardly they are the prefect Jews, praying morning, noon and night, participating and even coordinating the activities of the Synagogue, advising people about how to better practice their faith and even giving outward example of the same, inside they stink.

I’m not going to insult your intelligence by making the obvious comparison between these two men and people we all know in the Church, even it they be ourselves. It suffices only to see in these two examples the necessity of mustering the courage to see ourselves as we really are. And courage is the correct word, because it takes courage to face the truth of who we really are. “Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the fairest one of all?”*** But the magic mirror of the evil queen in Snow White, which shows only beauty where there is none, isn’t helpful, except that without it we wouldn’t have had a Grimm brothers fairy tale, a Disney film and a Magic Kingdom at Disney World. But we don’t need a magic mirror in our personal lives; we need a true mirror, one that shows us the naked truth, and we have to have the courage to step in front of it and take a long, hard look, and take whatever steps we must to fix whatever blemishes we see there.

The Blessed Apostle Paul, whose lesson to us today we cited in the beginning, looked into that mirror as he knew death was approaching, but he doesn’t want young Timothy to wait until death is upon him to look into it himself; and, his final words to his young friend in today’s second lesson, written just before he died, tell us why we should never be afraid to look into it ourselves: because when we do, there’s always someone else with us, standing over our shoulder.

But the Lord was at my side; he endowed me with strength, so that through me the preaching of the gospel might attain its full scope, and all the Gentiles might hear it; thus I was brought safely out of the jaws of the lion. Yes, the Lord has preserved me from every assault of evil; he will bring me safely into his heavenly kingdom; glory be to him through endless ages, Amen (2 Tim. 4: 17-18 Knox).

* This title has been used before, for the homily for the Second Sunday of Lent, but today's is a different homily.

** In the Churches of the Byzantine Rite, the "Lucan Jump" is in effect for this and the following weeks through December 28th. Cf. the second footnote attached to the post here for an explanation.

*** Snow White is a nineteenth-century German fairy tale which is today known widely across the Western world. The Brothers Grimm published it in 1812 in the first edition of their collection Grimms' Fairy Tales. It was titled in German: Sneewittchen (in modern orthography Schneewittchen) and numbered as Tale 53. The Grimms completed their final revision of the story in 1854. Walt Disney embelished the title for his 1937 film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

|