4:07 PM 10/24/2011 — Because there is typically no such thing as a pulpit in the Byzantine Churches, the priest or deacon who is to preach usually stands on the soleas in front of the Royal Doors, without notes or text, and preaches extemporaneously. Likewise, the Evangelion of the Byzantine Liturgikon is an annual one, without cycles for alternate years; and the temptation to drift far from the Scriptures of the day into less appropriate subject matter, rather than explore ever new and deepening mysteries in the passages provided, is often difficult to resist.

4:07 PM 10/24/2011 — Because there is typically no such thing as a pulpit in the Byzantine Churches, the priest or deacon who is to preach usually stands on the soleas in front of the Royal Doors, without notes or text, and preaches extemporaneously. Likewise, the Evangelion of the Byzantine Liturgikon is an annual one, without cycles for alternate years; and the temptation to drift far from the Scriptures of the day into less appropriate subject matter, rather than explore ever new and deepening mysteries in the passages provided, is often difficult to resist.

The purpose of this web site is to present my own approach to preaching in the parishes to which I have been assigned as pastor. In no way is it intended to present me as a model of preaching; to the contrary, it is a demonstration of the idea that a parish priest, even without advanced theological training, can try to infuse his preaching with something more than the mundane, emotional and simplistic.

Cognizant of my own limitations as an extemporaneous preacher, I preach from prepared texts which I write myself in advance. While some would condemn such preaching as artificial, preferring to preach “from the Heart,” as they say, the reality is that such preaching can easily become nothing more than an exercise in pride, resulting in homilies that lack focus, organization, compactness and substance, leaving the congregation either bored and wondering when it will be over, or embarassed at watching their parish priest trying to be more clever than he really is. It's all a question of knowing one's limitations, and being comfortable enough to accept and work with them.

So, what does it mean, then, to preach in a Byzantine way? While there is probably no exact answer to that question, one cannot go wrong by saying that the Eastern priest learns his art from the lessons of the Fathers of the Church. Unfortunately, the Fathers don't speak about preaching. In Apostolic and sub-Apostlic times, unlike today, preaching the word of God was not a subject of study or investigation in itself, anymore than breathing would be discussed by anyone in spite of the fact that we do nothing more frequently. The only one of the Fathers who comes close to discussing preaching per se is, appropriately enough, from Alexandria, Origen, whose statements are confined to simply reminding us to preach from the Scriptures, as all other sources are inferior. This apparent lack of comments on the subject of preaching should remind us of the old cliché: "Those who can, do; those who can't, teach." But this, in fact, is a lesson in itself, especially in light of the current trend in clerical circles for technique to supersede content in any discussion of preaching today.

Taking Origen at his word, the content of a homily is going to come from the Scripture of the day; but this opens a Pandora's Box. Historical criticism, literary criticism, source criticism, form criticism, redaction criticism, all of which form the matrix of what is so pompously called "higher criticism," arising from 19th century European rationalism, generally takes a secular approach, asking questions regarding the origin and composition of the text, including when and where it originated, how, why, by whom, for whom, and in what circumstances it was produced, what influences were at work in its production, and what original oral or written sources may have been used in its composition; and the message of the text as expressed in its language, including the meaning of the words as well as the way in which they are arranged in meaningful forms of expression. The principles of higher criticism are based on reason rather than revelation, and are speculative by nature. What the "higher criticism" leaves out, unfortunately, is rather important. We call it God.

Enter the Apostolic and post-Apostolic Fathers, for whom every word of the Old Testament points to Christ, and every word of the New Testament comes from Christ; and for whom every word of every sermon should instruct and inspire the faithful to embrace the Faith of Christ. Which is why Pope Paul VI, in 1970, following the close of the Second Vatican Council,—and perhaps mindful of the can of worms that council opened to the rationalists who were already descending on the Church's institutions of higher learning—warned us:

We particularly wish to emphasize at this time the fact that return to the Fathers of the Church is, in fact, part of the return to Christian sources without which it will not be possible to activate Biblical renewal, liturgical reform and the new theological research desired by the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council.

Needless to say, the rationalists disagreed, and plowed ahead to show that it was not only possible, but essential as far as they were concerned. There is no quicker way to anger a post-conciliar revisionist—one who believes the Holy Spirit finally decided to visit the Church for the first time in 1965—than to explain a passage of the Old Testament allegorically with a citation from one of the Fathers.

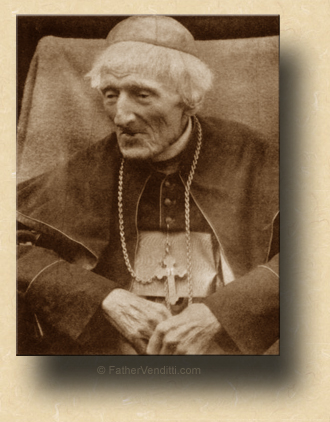

Ironically, it was a Roman Catholic convert from the Church of England whom I believe best personifies the attitude of the truly effective preacher for priests in the Byzantine Tradition: Cardinal Newman, who breathed the Fathers the way we breath oxygen; and what better introduction to his preaching priorities than his own words:

Brothers! spare reasoning;—men have settled long

That ye are out of date, and they are wise;

Use their own weapons; let your words be strong;

Your cry be loud, till each scared boaster flies.

Thus the Apostles tamed the pagan breast,

They argued not, but preach'd; and conscience did the rest.

[from "The Religion of Cain," Verses on Various Occasions.]

While still a Protestant, Newman, having graduated a fellow of Oriel College, Oxford, was appointed pastor of the university parish. It was considered a prestige appointment for one who had distinguished himself in sacred learning. But Newman saw it not as an intellectual reward but as a call to shepherd a flock. Mindful of the outlying districts of his parish which housed the servant class catering to the university, he built, with money from his mother, a chapel in the neighborhood of Littlemore to serve them. He couldn't celebrate the Sunday morning service there, since he was required at the university church where there was usually a guest preacher; so he provided the Littlemore congregation with Vespers, at which he could preach to them as their pastor. But his reputation as a preacher was well known; and, before too long, the Littlemore chapel was being filled to capacity with people from the university. The sermons he preached there, available under the title of Parochial and Plain Sermons, are deceptive, in that they give the impression of being highly cerebral. For this reason, it's important to remember that they weren't preached with scholars in mind. Laced through and through with the Fathers of the Church, Eastern and Western, they certainly must have taxed the intellects of the chimney-sweeps and charwomen to whom they were directed; but this is explained by the fact the Newman never talked down to anyone—it wasn't in his nature.

While still a Protestant, Newman, having graduated a fellow of Oriel College, Oxford, was appointed pastor of the university parish. It was considered a prestige appointment for one who had distinguished himself in sacred learning. But Newman saw it not as an intellectual reward but as a call to shepherd a flock. Mindful of the outlying districts of his parish which housed the servant class catering to the university, he built, with money from his mother, a chapel in the neighborhood of Littlemore to serve them. He couldn't celebrate the Sunday morning service there, since he was required at the university church where there was usually a guest preacher; so he provided the Littlemore congregation with Vespers, at which he could preach to them as their pastor. But his reputation as a preacher was well known; and, before too long, the Littlemore chapel was being filled to capacity with people from the university. The sermons he preached there, available under the title of Parochial and Plain Sermons, are deceptive, in that they give the impression of being highly cerebral. For this reason, it's important to remember that they weren't preached with scholars in mind. Laced through and through with the Fathers of the Church, Eastern and Western, they certainly must have taxed the intellects of the chimney-sweeps and charwomen to whom they were directed; but this is explained by the fact the Newman never talked down to anyone—it wasn't in his nature.

Moreover, Newman's style would have driven today’s “preaching gurus” to suicide. Every one of his sermons was read from a text which he had written out. From his sister's own testimony, he had a high, whiny voice very difficult to tolerate. With bad eyes, he buried his head in his text, and read for forty-five minutes or more. And each week, the little chapel's congregation grew more and more. Why?

The answer to that question is important; and touches on the distinction between the "remote" and the "immediate" preparation for preaching. The immediate preparation is a knowledge of the Scripture on which the homily is to be based, in addition to any other sources available, the structure, the content, and everything involved in just sitting down and working out what you're going to say. But the remote preparation is infinitely more important, and hard to put into words. To simplify it too much, remote preparation for preaching is a holy life. One can preach with the style—and even the content—of John Chrysostom or Fulton Sheen, and it won't mean a thing if it doesn't come from a holy man. People tolerated Newman's limitations as a public speaker because of his life, not because of his scholarship, style, brilliance or cleverness in the pulpit, and certainly not because of the structure, organization or "relevance" of his sermons.

If you want to know what it means to "preach from the Fathers," grab any one of Newman's sermons and read it. It doesn't mean that you artificially throw in a quote from some Father of the Church here or there which relates to the Scripture of the day; it means that you embrace the faith that the Fathers embraced (which necessitates rejecting the "faith" that the Fathers did not embrace), and do what you can to reproduce it in your life. Newman stuck to that approach all his life because it was his study of the Fathers that led him into the Catholic Church; and he figured that if it worked for him, it could work for others.

The best school of homiletics for any Eastern Christian priest, then, is meditation upon the sermons of the Fathers of the Church. The fact that their sermons are there for us to read should be lesson enough for many preachers today.