3:06 PM 9/9/2014 — We made mention last week to some of the other problems the Blessed Apostle Paul was addressing to his converts in Corinth, one of which was the fact that some of the Corinthian Christians were having recourse to civil courts to solve disputes between themselves. In our first lesson today he addresses this particular issue:

3:06 PM 9/9/2014 — We made mention last week to some of the other problems the Blessed Apostle Paul was addressing to his converts in Corinth, one of which was the fact that some of the Corinthian Christians were having recourse to civil courts to solve disputes between themselves. In our first lesson today he addresses this particular issue:

Are you prepared to go to law before a profane court, when one of you has a quarrel with another, instead of bringing it before the saints? You know well enough that it is the saints who will pass judgement on the world (I Cor. 6: 1-2 Knox).

Msgr. Knox uses the word “saints”; the New American Bible we read from at Holy Mass uses the phrase “holy ones.” We're used to the New American Bible “dumbing down” the Scriptures by avoiding words they think a third grader won't understand, but why they feel the word “saint” is beyond the average person in the pew is beyond me. In any case, what's important here is that the Apostle is not suggesting that we should take our disputes to people who are holy, as that would be a purely subjective judgment; “saints” was the word used by the early Christians to refer to themselves. In other words, he's saying that Christians should settle their differences within the Church.

In that light, the Apostle carries over what we had observed the last time we were looking at this Epistle, and gleaned from it our Number Six Rule for the Interior Life: don't be a lone ranger. Everything the Christian says, everything the Christian does, has to conform to what is believed and taught by the Church; and, he drives the point home by pointing out, in one of the lessons last week, that even the Apostle has no message of his own: his only message is Christ's, and his preaching of it is always subjected to the judgment of the Church, as evidenced by his own submission to the authority of Peter in Jerusalem when his own authority as an Apostle had been questioned. As a priest one is often asked by people what one thinks of something taught by the Church or said by the Pope, probably in an attempt to goad the priest into disagreeing with the Church on some issue; and, when that happens to me, I always respond by saying, “I'm not in management. I'm in sales.”

There's a lot of practical and moral wisdom contained in this first lesson today, and it's all pretty obvious. But there's one little tit-bit contained in this lesson that shouldn't be glossed over:

… it is a defect in you at the best of times, that you should have quarrels among you at all. How is it that you do not prefer to put up with wrong, prefer to suffer loss? (v. 7 Knox) …

… or, as the New American Bible, believe it or not, more clearly puts it, “Why not rather put up with injustice? Why not rather let yourselves be cheated?” (v. 7 NAB). What he's suggesting is that it is better to allow oneself to be treated unfairly rather than insist on justice at all costs and damage the unity of the Church in the process. And that's a hard pill for us, in our society, to swallow. As was mentioned some weeks ago in some homily I've already forgotten, we are obsessed in this country with the concepts of justice and fairness, and we pointed out how these things mean nothing to our Lord, as evidenced in the Parable of the Prodigal Son, the Parable of the Wheat and the Tares, the Sermon on the Mount, etc., etc.

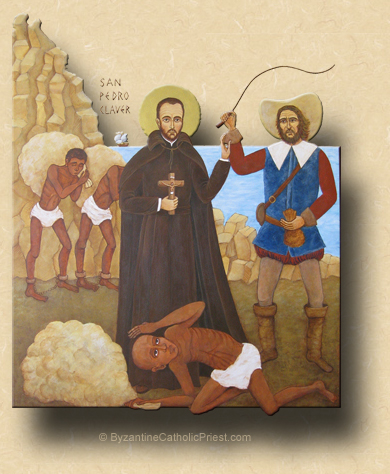

On the web site where I post these homilies for people to read, I always include some picture to go with each one; and, for the picture I used for the homily from last Saturday, when I gave you Father Michael's Number Six Rule, I chose a picture of a lovely stained glass window depicting the Council of Jerusalem from Acts 15, showing St. Paul submitting to the authority of St. Peter. I wish I knew where that window is, but I don't.

Many years ago, when I was just a few years ordained, I was stationed as parochial vicar—what they used to call an “assistant”—in a large suburban parish, and was playing host to a priest from outside the parish who had come to do a funeral for one of our parishioners whom he had known. When he introduced himself to me he seemed to imply that I should know his name, but I didn't, and this clearly annoyed him. It turned out that he was the founder and director some sort of charitable house for the homeless in another diocese that had become rather famous, and had become a favorite charity of actors and other sorts of people with whom he was often photographed; and, since I don't really pay attention to pop culture, I had never heard of it. You would know his name if I mentioned it to you, but that's not the point. As he was preparing for Mass he told me of how his new bishop had called him in to tell him that he was to be transferred, that he didn't think it was healthy for a priest to be involved in that kind of specialized ministry for too long, and that it was time for him to turn over this project, worthwhile as it was, to someone else. This, of course, would mean that he would no longer be a famous and important person, and this didn't sit well with him, so he told the bishop that he would leave the priesthood if he wasn't allowed to stay where he was. I don't know who the bishop was, but it was to his discredit that he backed down, and allowed the priest to stay. So, here was a priest who was doing good work, but who was nonetheless ruined by the fact that he was allowed to do what he wanted without being required to submit to authority.

The moral of the story is that, even if what one is doing is good work in and of itself, it does damage to the apostolate and to oneself if it is not in concert with the Church. I think that sometimes we fall prey to the temptation to view the Church the same way Thomas Pane suggested we think of government: as a necessary evil that we must tolerate for the sake of good order, but of which we should always be suspicious. I would tend to agree with him as far as the government is concerned, but not with regard to the Church, since the Church is the Body of Christ.

Toward the end of this lesson, St. Paul gets a little worked up in his rant about this:

Make no mistake about it; it is not the debauched, the idolaters, the adulterous, it is not the effeminate, the sinners against nature, the dishonest, the misers, the drunkards, the bitter of speech, the extortioners that will inherit the kingdom of God (vs. 9-10 Knox).

Now, there's a litany of rouges, isn't it? He goes on:

That is what some of you once were; but now you have been washed clean, now you have been sanctified, now you have been justified in the name of the Lord Jesus, by the Spirit of the God we serve (v. 11 Knox).

We might be taken aback that the Apostle would resort to such name calling, but you have to understand where he's coming from. He was out there in no man's land making more converts than the rest of the Apostles combined, and was being rewarded by being told that he had no authority to do it, possibly out of jealousy; and, while he could have responded to it by becoming indignant and just going his own way—and possibly ending the spread of the Gospel then and there—he chose instead to go to Jerusalem and throw himself at the mercy of St. Peter, who, of course, did the right thing.

How could he take that chance? Because, for him, it wasn't a chance. As was mentioned last Saturday, if what we're doing is somehow at odds with what the Church directs, then humility requires us to accept that what we're doing is wrong. So, whatever Peter's answer was going to be, he was going to submit to it. And you can see why he has no tolerance for any Christian who doesn't have the same attitude. And it is not a coincidence that, after his participation in the Council of Jerusalem, he goes back into the field and has the most productive period of his life, because now the cloud over him is lifted.

Our relationship to Christ must be a deeply personal one, otherwise we can make no progress in the Interior Life, but it can't simply be “me and Jesus”; it has to be “me and Jesus in the Church,” otherwise our relationship is not with the real Jesus, and we're only fooling ourselves.