Power Failures Make for Short, Generic Homilies.

Lessons from cycle A of the Dominica, according to the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite:

Ezekiel 33: 7-9.

Psalm 95: 1-2, 6-9.

Romans 13: 8-10.

Mathew 18: 15-20.

The Twenty-Third Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

8:05 AM 9/7/2014 — Those of you who were with us yesterday for the Marian Festival for Our Lady's Birthday know that we suffered a power failure just as Holy Mass began. And as the day was ending the question became, “What are we going to do about Sunday?” as it was unclear whether we would have power today. My initial instinct was to cancel today's Mass, since without power we can't open the Shrine downstairs: there would be no lights and no running water, so the toilets would not be available, and I can only guess what condition the port-o-potties are in after all the people we had here yesterday; and because none of the alarms would be working, we couldn't allow anyone inside at all. And this is not a parish: people come here from all over, and we have no way to call people and tell them that services are canceled. Because we're not a parish, we have no obligation to provide a Mass on Sunday or any other day, but many people have come to expect it; and, since Mass here doesn't begin until noon, I was afraid that many people, showing up and seeing signs that there is no Mass today, wouldn't be able to find a later Mass somewhere else. And with no power in the chaplaincy, I had no way to really prepare a decent homily; and, as you know, my own sin of pride won't permit me to just stand up and wing it—I have to be prepared. 8:05 AM 9/7/2014 — Those of you who were with us yesterday for the Marian Festival for Our Lady's Birthday know that we suffered a power failure just as Holy Mass began. And as the day was ending the question became, “What are we going to do about Sunday?” as it was unclear whether we would have power today. My initial instinct was to cancel today's Mass, since without power we can't open the Shrine downstairs: there would be no lights and no running water, so the toilets would not be available, and I can only guess what condition the port-o-potties are in after all the people we had here yesterday; and because none of the alarms would be working, we couldn't allow anyone inside at all. And this is not a parish: people come here from all over, and we have no way to call people and tell them that services are canceled. Because we're not a parish, we have no obligation to provide a Mass on Sunday or any other day, but many people have come to expect it; and, since Mass here doesn't begin until noon, I was afraid that many people, showing up and seeing signs that there is no Mass today, wouldn't be able to find a later Mass somewhere else. And with no power in the chaplaincy, I had no way to really prepare a decent homily; and, as you know, my own sin of pride won't permit me to just stand up and wing it—I have to be prepared.

Thankfully, our power came back on around 3:00 this morning; but it occurred to me that it might be a good opportunity to explore with you why the Catholic Church is so obsessive about this thing we call the “Sunday Obligation.”

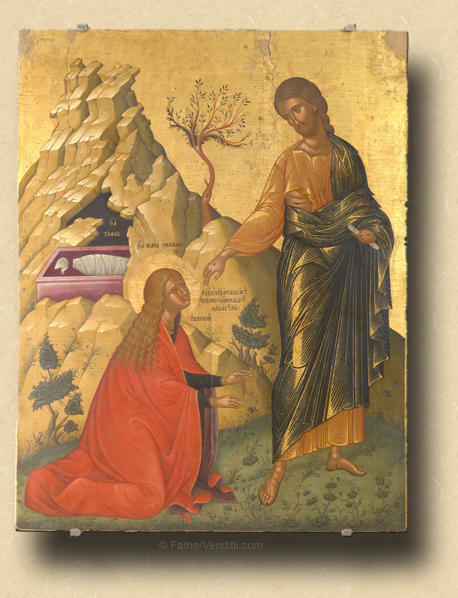

I would like you to think back to Easter time, and the morning that Mary the Wife of Clopas, Mary Magdalene and Salome went to the tomb. There are, of course, implications both theological and spiritual to the fact that these women, and not the Apostles, are the first to see the Risen Lord. There are other spiritual lessons as well which we can derive from the most arcane details: the miraculous rolling away of the stone; the angel dressed in white; the fact that the women do not come to the tomb empty-handed; the fact that they do not, at first, recognize our Lord. All of these have significance, but we focus today on only one: the fact that all of it happens on a Sunday.

Before our Lord’s Passion, his followers kept the same Sabbath as all the other Jews around them: beginning Friday at sundown and ending Saturday at sundown. The tradition comes from God himself, as spoken to the Hebrew people through Moses: “Thou shalt remember the Sabbath and keep it holy.” But almost immediately after our Lord’s resurrection, the Christians began to keep another day. Jesus rises from the dead on a Sunday. His resurrection is witnessed by these three women at daybreak, just as the sun itself is rising in the East. And it was almost immediate that the Apostles and their disciples began to refer to Sunday as the “new Sabbath”; and, to this day, when a Christian examines his conscience in preparation for confession, when he gets to the Third Commandment, he understands it to mean that he should keep holy the “Lord’s Day,” meaning Sunday.

It’s also important to note the parallel the early Christians made between the rising of Christ from the dead and the time of day at which it happened: just as the sun was rising in the East; hence, the earliest manuscripts we have which describe how the first Christians worshiped show them performing the Lord’s Supper on an altar which faces the East, as they themselves faced the East; and they did this, as far as possible, just as the sun was rising, because they saw in the rising sun a symbol of our Lord’s resurrection.

And for a thousand years, churches, whenever possible, faced the East; and, when it was not possible for a church to face East, they pretended that it did, with everyone, priest and congregation, facing the same way as well, as if to see, in the rising sun, our risen Lord. The spiritual implications are unmistakable: Jesus is the rising Sun which should light our day from its first moments. The whole day becomes different when it is illumined by the Lord.

Unfortunately, like all of the most ancient traditions of the Church, it’s old and easily becomes passé in the minds of Christians. The “Sunday obligation,” as we have come to call it, becomes nothing more than something we were taught in our catechism; just another rule that we’re supposed to obey, and confess when we don’t. And when something is viewed as nothing more than a rule to be followed for its own sake, the motivation for following it becomes pretty weak—as do the excuses we grant ourselves for ignoring it from time to time: “It’s the first day of Spring.” “It’s the last day of Summer.” “It’s a long weekend and I’ve got a chance to get away.” “It's raining outside so I don't want to drive.”

Sometimes it’s helpful to remember what many of the early Christians went through in their efforts to keep the Lord’s Day: steeling away to underground caverns in cemeteries, or hidden away cellars in the homes of wealthy Christians, to celebrate the Lord’s Supper during times of violence against the Church, endangering—and sometimes giving—their lives for the privilege. For them, the motivation was not a rule they had to follow or an obligation they would have to confess if they didn’t; it was the promise of receiving into themselves the Body and Blood—the Soul and Divinity—of Jesus Christ in Holy Communion. They did not—and could not—see it as a burden.

If we have come to see it that way—as a burden—it’s because, somewhere along the way, we’ve lost our connection with those earliest Christians who handed these traditions on to us down through the centuries. Reconnecting with them—and to the traditions of our faith—is something that can only be done by each one of us in our own hearts.

Here's an exercise that might help to clarify our minds on the issue: next time to you get up on Sunday morning to come to church, ask yourself why. Is it because it's an obligation you need to fulfill or else you'll feel guilty? Or is it for the reason that the three women went to the tomb on the first day of the week: because they loved our Lord?

|