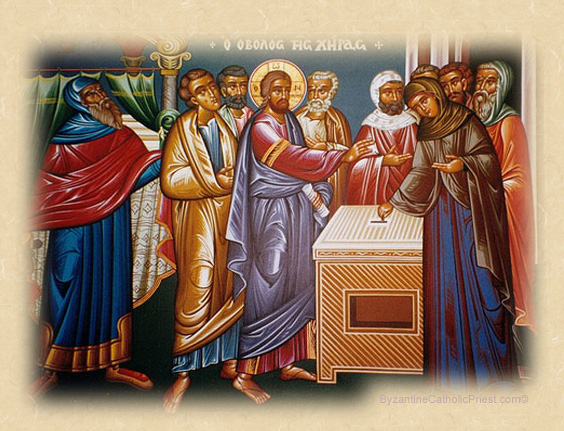

God loveth the cheerful giver.2 Cor. 6:16-7:1;*

Luke 5:1-11.** The Seventeenth Sunday after Pentecost. The Second Sunday after the Holy Cross. The Conception of the Holy Prophet & Baptist John.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

3:42 PM 9/23/2012 — Whenever the Gospel of the calling of the first disciples occurs, I routinely have focused our attention on the great leap of faith made by the Apostles in answering the Lord's call, especially that of the Blessed Apostle Peter; and, I did so by referencing the life of Blessed John Henry Newman, about whom I won't speak since you should know all about him by now.

For the sake of variety, we'll put that aside this week, and look instead at the Apostolic reading from Paul's Second Epistle to the Corinthians which, on the surface, seem just a boring yet practical admonition about alms giving, and which contains one of those verses of Holy Writ which is so commonly thrown about that no one actually bothers to stop and think about it: “God loveth a cheerful giver.”

It's interesting to note that Paul, here, is quoting a line from the Book of Proverbs, but he's got the quote wrong; we don't complain because his rendering is actually an improvement. The original text from the Old Testament says that God “praiseth the cheerful giver”; we don't know whether Paul simply remembered it wrong or whether he purposely altered the text to make a point. God loves those who give with joy, not only when it involves alms or donations for the poor and needy, but in any circumstance in which someone offers a sacrifice which has been genuinely costly for him. That could include the acceptance of a painful trial of some sort, or even the resistance to a temptation.

The key word, of course, is not the one which Paul transposes, but the cheerfulness with which such a sacrifice is to be made, and reminds us of the similar lesson taught to us by our Lord which we read each year as we enter into the Great Fast, about how, when we fast, we are to “wash our face and comb our hair”—easier for some than for others—so that no one knows we are fasting except God.

This brings to mind something that happened while the priests of our eparchy were on retreat last week. Most of the priests of our eparchy had not seen me in over a year, and everyone was coming up to me and saying things like, “Oh, my God! You've lost so much weight. You look great! How did you do it?” And that's always a very awkward thing for me, since I had nothing to do with it. They bypassed my stomach and two-thirds of my intestines; how could I not lose weight? But I didn't let on. I sat there just soaking it in, and I enjoyed it; so, I was not taking the suggestion of the Apostle. I was allowing myself to benefit from the praise for having done something that St. Paul would say should have been done more modestly; in fact, I was worse, because I was accepting praise for something I hadn't done at all: after all, I didn't perform the surgery on myself.

But, to return to our original point: whenever we endure a sacrifice for our Lord, whether it's the giving of alms or giving to the church, or, as we mentioned before, the broader interpretation of suffering willingly through some sort of painful trial or heroically resisting a temptation to commit some sin, how we behave after it's happened is almost as important as it happening in the first place.  That doesn't mean that we should not enjoy some sort of personal satisfaction for having done the right thing; in fact, sometimes that can be of great spiritual benefit. Think back to some occasion when you were severely tested, and you resisted the temptation, and the temptation finally past; was there not a feeling of great peace and closeness to our Lord when it was over? Conversely, on those occasions when you failed to resist the temptation, and later went to the priest to confess your sin to Christ, acknowledging your failure candidly, and having the burden of it lifted completely from your shoulders by the Lord, did you not have the same feeling? That doesn't mean that we should not enjoy some sort of personal satisfaction for having done the right thing; in fact, sometimes that can be of great spiritual benefit. Think back to some occasion when you were severely tested, and you resisted the temptation, and the temptation finally past; was there not a feeling of great peace and closeness to our Lord when it was over? Conversely, on those occasions when you failed to resist the temptation, and later went to the priest to confess your sin to Christ, acknowledging your failure candidly, and having the burden of it lifted completely from your shoulders by the Lord, did you not have the same feeling?

What concerns St. Paul the most, it seems, is that we don't fall into the trap of allowing the sacrifices we endure to define us, and that's a very easy trap to fall into. And this can happen both to people who suffer willingly through voluntary sacrifice, and those who have some trial thrust upon them against their will. They will walk around with a long face, and may even say out loud how much they are going through. And we've all met these people; we may even be one of them: those who never tire of telling everyone they meet their tales of woe. “Let me tell you about my daughter-in-law! What she said to me the other day, you wouldn't believe...blah, blah, blah.” Now, some of that might be a form of therapy; but, more often than not, it's just complaining. And when we have to complain about our sacrifices in order to cope with them, how can we benefit spiritually from them? This, I think, it what the Apostle really means in his Epistle: we cannot offer up to God a sacrifice which we don't make willingly and with joy.

When the Holy See released that instruction some years ago, reminding bishops that they cannot ordain to the celibate Priesthood any man who gives evidence of being a homosexual, it got a lot of attention in the press, and people who knew nothing about the nature of the Holy Priesthood were saying things like, “What does it matter that he's homosexual? He's not getting married anyway.” But the whole point is that it's supposed to be a sacrifice; and, what's the point of sacrificing something that you don't want in the first place? And if you want to take the more narrow view of St. Paul's passage, and apply it strictly to the subject of alms giving or giving to the church, it would mean that you don't give from your surplus; you give from what you actually need for yourself. Otherwise, where is the sacrifice?

A lot of the spiritual writers of the Middle Ages talk about saying a prayer of thanks to God whenever some cross is given to us, because any cross we endure for our Lord is just one more rung on the ladder to Heaven; and, who wants to walk into Heaven with a sour puss? When Judas arrived at the Garden of Gethsemane with the soldiers, Peter tried to fight them off, and our Lord corrected him, and then said to Judas, “Do what you have come to do.” God does “loveth the cheerful giver,” because the cheerful giver behaves like Christ.

Father Michael Venditti

* By mistake, the Epistle for the 18th Sunday was read today, instead of the one actually indicated for this Sunday. See the note below for the source of the confusion. Next week, the Epistle which should have been read today will be read instead to make up the difference.

** The four Gospels are all read in their entirety in the Byzantine Church, and the reading of each begins with a great feast. The Gospel of St. John begins with the Feast of Feasts, Pascha, and is read until Pentecost. The Gospel of St. Matthew begins with Pentecost, and is read until the Feast of the Holy Cross, when the Gospel of St. Luke is read all the way through until the Great Fast. The first Sundays in the Matthew cycle and the Lucan cycle are of the call of the apostles Peter and Andrew, James and John, indicating that these Gospels also call us to follow after Jesus our Lord. The Gospel of St. Mark is read during the Great Fast, but because there is no Liturgy during the week, the remaining sections are read in the last six weeks of the Matthean and Lucan cycles. This is why we begin the reading of Luke’s Gospel on the Sunday after the Holy Cross no matter where we are in the cycle of "Sundays after Pentecost." This year there is a discrepancy of one week until Friday, December 28th, 2012; however, even though the Gospel for the 18th Sunday is read on the 17th Sunday, that Sunday remains the Seventeenth Sunday after Pentecost, and the other texts of the Liturgy for that day, including the Apostlic reading, remain unchanged. In the Byzantine Churches, this is commonly called "the Lucan jump."

The Greek Church actually labels these Sundays as “Sundays after the Holy Cross.” The historical context of this practice was the Greek custom of marking the birthday of the Emperor Augustus on September 23rd, which they regarded as the first day of the Church year. It was not until the fall of the empire that the new year observance was moved to September 1st.

|