11:32 AM 9/22/2019 — An odd assortment of lessons from Sacred Scripture punctuate the Holy Sacrifice today. The Prophet Amos thunders against the exploitation of the poor by ruthless profiteering merchants who despise the needy and make money off them; tampering with the scales and selling them defective goods, raising prices by taking advantage of shortages. But don’t make the mistake of thinking that this is some kind of Biblical condemnation of Capitalism, since, in our Gospel lesson, Capitalism is very much the hero. Our Lord tells us the parable of the unjust steward who is forced to give an accounting of his services. Afraid that his duplicity is about to be exposed, he engages in an almost reckless gamble, taking it upon himself to reduce the debt owed to his master by the creditors in the hope that one of them might hire him should his own master fire him; and, our Blessed Lord, perhaps with a tinge of sadness, appends the story with the statement:

11:32 AM 9/22/2019 — An odd assortment of lessons from Sacred Scripture punctuate the Holy Sacrifice today. The Prophet Amos thunders against the exploitation of the poor by ruthless profiteering merchants who despise the needy and make money off them; tampering with the scales and selling them defective goods, raising prices by taking advantage of shortages. But don’t make the mistake of thinking that this is some kind of Biblical condemnation of Capitalism, since, in our Gospel lesson, Capitalism is very much the hero. Our Lord tells us the parable of the unjust steward who is forced to give an accounting of his services. Afraid that his duplicity is about to be exposed, he engages in an almost reckless gamble, taking it upon himself to reduce the debt owed to his master by the creditors in the hope that one of them might hire him should his own master fire him; and, our Blessed Lord, perhaps with a tinge of sadness, appends the story with the statement:

And this knavish steward was commended by his master for his prudence in what he had done; for indeed, the children of this world are more prudent after their own fashion than the children of the light (Luke 16: 8 Knox).

It sounds confusing. Is our Lord praising the steward or condemning him? It’s a good occasion for us to examine how the parable, as used by our Lord, is a particular Middle Eastern form of teaching which, for one reason or another, has a hard time penetrating our literal, Western minds. One good way to look at a parable is to consider it to be a sort of verbal icon.

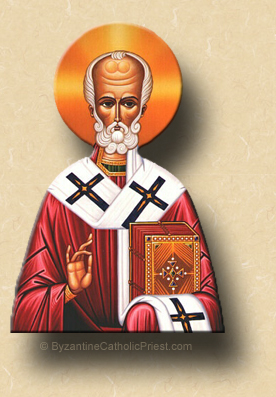

I spent many years serving in an Eastern Catholic Church and, as you know, icons are a very important part of the spirituality of Eastern Christianity; and, while most of you, I'm sure, would be able to identify a Byzantine icon when you see one, very few people truly know how to read them properly. They are not meant to be realistic representations. When our Lord or a saint is depicted in an icon, he does not look like a normal human being: the head and eyes are much too large, the mouth is much too small, almost as if the saint being represented is some sort of space alien; but, those distorted features speak volumes.  The head is large in proportion to the body because the saint contemplates the will of God; the eyes are large and the mouth is small because the saint's eyes of faith are always alert for the will of God, which he obeys without question or comment. If he's a bishop, he holds one hand in a blessing and the book of the Gospels in the other; if he's a martyr, he'll often hold instruments of the passion. The icon is not meant to show us the saint as he actually looked when he walked this earth, but rather to show us, in a symbolic and mystical way, the primary features of why he's a saint.

The head is large in proportion to the body because the saint contemplates the will of God; the eyes are large and the mouth is small because the saint's eyes of faith are always alert for the will of God, which he obeys without question or comment. If he's a bishop, he holds one hand in a blessing and the book of the Gospels in the other; if he's a martyr, he'll often hold instruments of the passion. The icon is not meant to show us the saint as he actually looked when he walked this earth, but rather to show us, in a symbolic and mystical way, the primary features of why he's a saint.

A parable is the same sort of thing, except it's all done with words instead of pigments. The story of the parable is not supposed to make sense. The events of the story symbolize deeper realities; and, in the case of the parable of the shrewd and unscrupulous steward, the lesson our Lord teaches us is a spiritual one, not a social or economic one. That great Father and Doctor of the Church, Saint Augustine, tells us what this parable is really all about:

Why did the Lord propose this parable? [he asks.] Not because that servant was a model for us to imitate. Nonetheless, the worldly-wise steward had an eye to the future. So too should the Christian have this determination to secure his eternal reward. If not, the steward puts him to shame (Sermon 359, 9-11).

We are well accustomed to seeing people make unbelievable sacrifices to improve their life-style or standard of living. At times we may be taken aback by the lengths some people will go to acquire more wealth, more power, more fame. The media frequently—almost constantly—trains a spotlight on our society’s most ambitious people and their so-called accomplishments; but, are any of these people thinking of salvation? What would happen if these very same people were to put the same amount of zeal into the purification of their souls in anticipation of their final judgment? For one thing, they wouldn’t be on TV or the covers of magazines, and we probably would never have heard of them.

What zeal men put into their earthly affairs! [says Saint Josemaría.] Dreaming of honors, striving for riches, bent on sensuality! Men and women, rich and poor, old and middle-aged and young and even children: all of them alike.

When you and I put the same zeal into the affairs of our soul, then we’ll have a living and working faith. And there will be no obstacle that we cannot overcome in our apostolic works (The Way, 317).

I particularly like the last sentence of that quote from his book called quite simply, The Way. Even our apostolic works, even what we choose to do for the poor and the needy or the betterment of this earthly realm is made fruitful by the pursuit of personal holiness. No one ever went to heaven solely because of what he did for his fellow man; he went to heaven because what he did for his fellow man he did because he had already become a saint, and would have gone to heaven even if he had locked himself up in a monastery and done nothing pray. In fact, a lot of people go to heaven that very way.

At the conclusion of His parable, the Lord reminds us of an ineluctable fact:

No servant can serve two masters. He will either hate one and love the other, or be devoted to one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon (Luke 16: 13 NABRE).

We have only one Lord. We must serve Him with all our heart, with the natural gifts He Himself has given us, using every licit means throughout our lives to ensure both our own salvation and that of those we encounter along the way. The coherent Christian does not devote one part of his attention to God and another to the affairs of this world; he must convert both into the service of God and neighbor, contributing to the sanctification of the world primarily by sanctifying himself.