3:31 PM 9/20/2015 — There's an old cliché: You learn something new every day; and, if you've attended services here before you've probably noticed that I like to pretend that I know everything, which I don't. No body does. Sherlock Holmes once said to Dr. Watson: “It isn't important what you know; it's what you can make people think that you know that's important”; and I'm very good at that. The problem with being an annoying know-it-all like me is that, when you finally stumble upon something you don't know, it's very humbling, which is probably good. That point was brought home to me not long ago by someone who comes here for Holy Mass regularly, who pointed out to me that the translation of the Holy Scriptures presented to us in the current edition of the Roman Missal is not exactly the one I thought it was. While it's certainly based on the Revised Edition of the New American Bible, it's actually different in many places, and it's a shame that we don't know who's responsible for it, because it's quite good. A case in point is today's first lesson from the Book of Wisdom, the translation of which from the Hebrew is really quite striking, and makes clear a passage that wasn't all that clear before:

3:31 PM 9/20/2015 — There's an old cliché: You learn something new every day; and, if you've attended services here before you've probably noticed that I like to pretend that I know everything, which I don't. No body does. Sherlock Holmes once said to Dr. Watson: “It isn't important what you know; it's what you can make people think that you know that's important”; and I'm very good at that. The problem with being an annoying know-it-all like me is that, when you finally stumble upon something you don't know, it's very humbling, which is probably good. That point was brought home to me not long ago by someone who comes here for Holy Mass regularly, who pointed out to me that the translation of the Holy Scriptures presented to us in the current edition of the Roman Missal is not exactly the one I thought it was. While it's certainly based on the Revised Edition of the New American Bible, it's actually different in many places, and it's a shame that we don't know who's responsible for it, because it's quite good. A case in point is today's first lesson from the Book of Wisdom, the translation of which from the Hebrew is really quite striking, and makes clear a passage that wasn't all that clear before:

Let us beset the just one, because he is obnoxious to us; he sets himself against our doings, reproaches us for transgressions of the law and charges us with violations of our training (2: 12 RM3*).

And if you're any kind of serious Catholic at all—and I presume that those who come here to our Shrine are—then you have to identify with that at some level: you have to have had the experience of dealing with friends or family members or both who have drifted away from their faith, and with the abuse you can sometimes receive when you try to call them back to the faith in which they were raised. As chaplain here, it's a common theme I hear from people all the time who visit with us: “My son (or my daughter) has stopped going to Church” or “they're living with someone outside of marriage” or whatever; and it's heart-breaking. “I didn't raise them that way.”

Now, the lesson in the Missal skips a number of verses at this point, but the whole passage from Wisdom is really quite insightful. The one being quoted here is the person who is being criticized for leaving the faith; so, the passage is putting us in the shoes of the one who's left the faith, and is now being lectured by someone for doing so; and, the passage goes on with him saying to himself:

He professes to have knowledge of God and styles himself a child of the Lord. / To us he is the censure of our thoughts; merely to see him is a hardship for us, / Because his life is not like that of others, and different are his ways. / He judges us debased; he holds aloof from our paths as from things impure. / He calls blest the destiny of the righteous and boasts that God is his Father (v. 13-16 NABRE).

This imaginary speaker who's being quoted is trying to paint a picture of the one calling him back to his faith as someone who is intolerant, self-righteous and rude. I particularly like the way the Roman Missal translates the first verse of today's lesson, when it says, “Let us beset the just one, because he is obnoxious to us …” And if you have ever been in the position of feeling compelled to say something to someone—a friend, a neighbor, a son or daughter—about how they are living, and had the guilt trip thrown back in your face, and made to feel that you're walking that tight-rope between speaking the truth and the sin of pride, you can almost feel the voice of the one you love in this angry quotation from the Book of Wisdom.

Of course, the official interpretation of this passage is that the one being spoken of so angrily is our Lord, because He did call His people back to a life of righteousness and did boast that God is His Father. But there's no reason why we can't see ourselves in it, too, especially when we find ourselves in that heart-breaking situation when someone we love has succumbed to the temptations of the world and thrown off the faith in which they were raised. And on those occasions when we just couldn't hold back, and risked the sin of pride, and said something because we felt we had a duty to our Lord to do so, and we get that angry response in return, accusing us of being obnoxious, butting in where we're not wanted, sometimes even being pushed out of someone's life entirely: “… merely to see him is a hardship for us,” says this unknown sinner in the Book of Wisdom, “Because his life is not like that of others, and different are his ways” (vs. 14 & 15 NABRE).

Why is that? Why is it a hardship for the sinner to even be in the presence of the practicing Cathoic? When we confront a friend or relative, a son or daughter, a sibling or a cousin or anyone close to us who has left the faith, and he gets angry and accuses us of meddling, and doesn't speak to us for weeks or months or years, why is that? Because, in the back of his mind, in the deep recesses of his conscience, the sinner always knows he's a sinner. He can convince himself that his sin is not really a sin, that his way of life is just like everyone else's, because it probably is. And he justifies this rationalization by pointing out what he believes is the hypocrisy of the religious person.

And that's where the lesson as given in the Missal picks up again: “Let us see whether his words be true; let us find out what will happen to him” (v. 17 RM3). And this is where we find ourselves feeling guilty about committing the sin of pride, because we know our sins: we examine our consciences, we go to confession, we know we're far from perfect. We end up questioning our right to even say anything. This is especially true if the soul of the one we're concerned about is our own child, because then we're torn between what we believe is our obligation as a parent, and the reality of our own sins and imperfections. “Should I say something or shouldn't I?” We don't know what to do.

And this is precisely where our Blessed Lord, in today's Gospel lesson, provides an answer:

They came to Capernaum and, once inside the house, he began to ask them, “What were you arguing about on the way?” But they remained silent[, because t]hey had been discussing among themselves on the way who was the greatest. Then he sat down, called the Twelve, and said to them, “If anyone wishes to be first, he shall be the last and the servant of all.” Taking a child, he placed it in their midst, and putting his arms around it, he said to them, “Whoever receives one child such as this in my name, receives me …” (Mark 9: 33-36 RM3).

If we go back to the official interpretation of the Book of Wisdom, in which the imaginary sinner is speaking not about us, but about our Lord, how did our Lord respond to that abuse? He gave up His life on the Cross for that sinner. Not right away, of course. He continued his mission of preaching, of healing the sick, of associating with and giving hope to the outcast, of scandalizing the Pharisees for his association with sinners. He didn't shy away from pointing out people's sins; quite the contrary.  How many times did He rebuke the Pharisees for their hypocrisy? Did He not chastise the woman at Jacob's well in Samaria for the revolving door into her bedroom? Did He not tell the woman caught in adultery, “Go and sin no more”? Of course He did. Our Lord doesn't tolerate sin, but He does forgive it.

How many times did He rebuke the Pharisees for their hypocrisy? Did He not chastise the woman at Jacob's well in Samaria for the revolving door into her bedroom? Did He not tell the woman caught in adultery, “Go and sin no more”? Of course He did. Our Lord doesn't tolerate sin, but He does forgive it.

One of the most telling episodes in the life of our Blessed Lord was when he called the Apostle Matthew, a politician who had gotten rich by stealing everyone's tax money. When our Lord met him, He didn't lecture him about what a horrible sinner he was; instead, He invited Himself to dinner,—a dinner paid for with ill-gotten gains—and all the Scribes and Pharisees were terribly upset:

The Pharisees saw this, and asked his disciples, "How comes it that your master eats with publicans and sinners?" Jesus heard it, and said, "It is not those who are in health that have need of the physician, it is those who are sick"** (Matt. 9: 11-12 Knox).

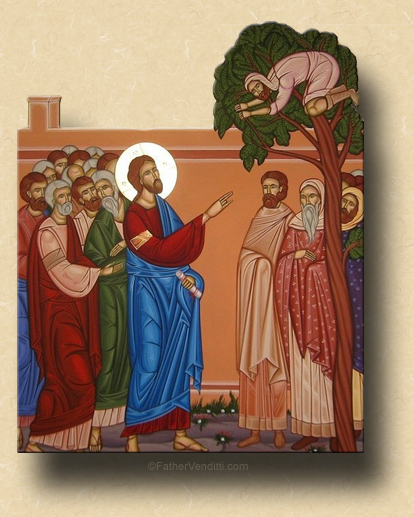

When our Lord was passing through the city of Jericho, he saw a man named Zacchaeus sitting in a sycamore tree; he had climbed up there because he was kind of short, and wanted a better view of the parade. And he also was known to be a great public sinner, and when our Lord saw him up there, He didn't say, “Come down out of that tree, Zacchaeus, so I can kick your butt and straighten you out.”

“Zacchaeus,” he said, “make haste and come down; I am to lodge to-day at thy house.” And he came down with all haste, and gladly made him welcome. When they saw it, all took it amiss; “He has gone in to lodge,” they said, “with one who is a sinner.” But Zacchaeus stood upright and said to the Lord, “Here and now, Lord, I give half of what I have to the poor; and if I have wronged anyone in any way, I make restitution of it fourfold” (Luke 19: 5-8 Knox).

Why? Why would Zacchaeus do that? Jesus didn't give Zacchaeus sight when he was blind, or make him whole when he was crippled, or raise his dead daughter to life, things He had done for others. All our Lord did for Zacchaeus was have a cup of coffee with him in his house. To us it may not seem like much, but to Zacchaeus it meant everything, and it changed his life.

For those of us who love our Lord there will always be people in our lives who won't measure up. The family that prays together doesn't always stay together, and even children raised in the best of homes can go astray. How we respond to them can either push them farther away or it can draw them back. Maybe not right away … maybe a simple seed of kindness and understanding we plant now won't take root and bare fruit until long after we're dead. There's no rule in life that we're entitled to see the results of the good we do. But that doesn't mean we shouldn't do it.

* Roman Missal Third Edition.

** Consistent with the practice of the time, Msgr. Knox does not provide quotation marks in his translation, setting off direct quotes simply by means of capitalization. When citing his translation, I provide the punctuation for the sake of clarity.