Rubrics Are Our Friends.

The Twenty-Second Monday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the primary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Thessalonians 4: 13-18.

• Psalm 96: 1, 3-5, 11-13.

• Luke 4: 16-30.

The Third Class Feast of Saint Stephen, Confessor.*

First & second lessons from the common "Os justi…" of a Confessor not a Bishop, third from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ecclesiasticus 31: 8-11.

• Psalm 91: 13-14, 3.

• Luke 19: 12-26.

FatherVenditti.com

|

7:40 AM 9/2/2019 —

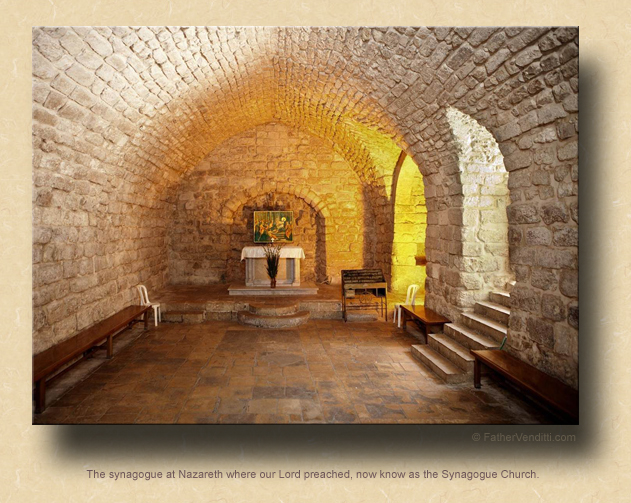

Today's Mass presents to an example of something found in only one of the four Gospels. Matthew and Mark mention very matter-of-factually that Jesus, upon returning to His home town—or, as Mark puts it, “his own country” (6: 1)—began to teach in the synagogue on the sabbath, and they both make mention of how everyone was impressed with His preaching. It's not surprising. I remember the first time I went home to preach in my native parish: everyone comes up afterward to tell you how wonderful it was. Of course they're going to say that; you're the home town boy. For some reason, Saint John ignores this event altogether; Saint Luke, on the other hand, is the only one of the Evangelists who actually tells us what the sermon was about. It's important that we put this synagogue visit into its proper context.

The synagogue service was very orderly and regimented. It began with the Shema prayer from Deuteronomy 6: 4: שְׁמַע, יִשְׂרָאֵל: יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ, יְהוָה אֶחָד. (Sh'ma Yis'ra'eil Adonai Eloheinu Adonai echad): “Hear, O Israel! The Lord is God. The Lord is One.” Then would follow readings from the five Books of Moses, lessons from the early prophetic books of Joshua, Judges, 1 & 2 Samuel, 3 & 4 Kings, and sometimes from the later prophets, all done in Hebrew, and all done according to a lectionary for the season of the year, just as we do at Holy Mass. Then there was a sermon in the vernacular language, in the case of the synagogue in Nazareth, Aramaic; and it did not have to be a member of the rabbinical class who conducted the service: any learned man could be called upon to do this, and our Lord was certainly a very prominent and learned man. He returns to Nazareth after performing His first miracle in Cana, and had become famous with a trip to Jerusalem during which He made headlines by driving the money lenders out of the temple; so, in these early days, our Lord was very much in demand, and was frequently asked by presidents of synagogues to preach, which is why His Apostles often addressed Him as “Rabbi.” Now, He was coming home to visit His own home-town synagogue, and everyone who was anyone was going to be there.

So, He finally arrives as arranged to do the service. As Saint Luke begins his account, the שְׁמַע, יִשְׂרָאֵל has already been prayed, the readings from the prophets are finished, and our Lord has to decide which of them he's going to preach about. He's handed the scroll of the Book of Isaiah. It's not clear whether he reads from it or simply recites it from memory, because he quotes for them the first two verses of chapter 61, but adds a few words from chapter 58:  “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me; he has anointed me, and sent me out to preach the gospel to the poor, to restore the broken-hearted; to bid the prisoners go free, and the blind have sight; to set the oppressed at liberty, to proclaim a year when men may find acceptance with the Lord, a day of retribution” (Luke 4: 18-19 Knox). He hands the scroll back to the attendant, and says, “This scripture which I have read in your hearing is to-day fulfilled” (v. 21). “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me; he has anointed me, and sent me out to preach the gospel to the poor, to restore the broken-hearted; to bid the prisoners go free, and the blind have sight; to set the oppressed at liberty, to proclaim a year when men may find acceptance with the Lord, a day of retribution” (Luke 4: 18-19 Knox). He hands the scroll back to the attendant, and says, “This scripture which I have read in your hearing is to-day fulfilled” (v. 21).

I don't think that was the totality of our Lord's homily—he probably had more to say than that—but that's all Saint Luke tells us, aside from the fact that everyone was very moved and, as the Evangelist puts it, “were astonished at the gracious words which came from his mouth” (v. 22).

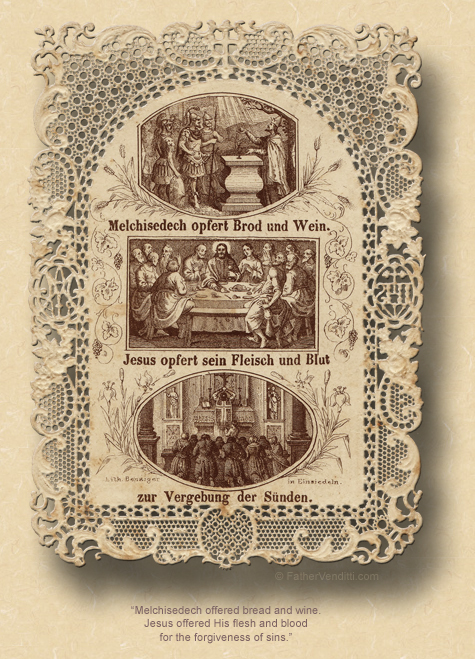

Following the homily there was a symbolic offering of bread and wine in the manner of the Old Testament example of Melchizedek, in Hebrew called the בְּרָכָה (berakhah), and the prayers used for this have become part of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass: at the Offertory, the priest prays two nearly identical prayers, one over the bread and one over the wine, which begin with the words, Benedictus es, Dómine, Deus universi…—“Blessed are you, Lord God of all creation…”, lifted word for word from the synagogue service of our Lord's time.

So, what's the point of all this? I think it's beneficial sometimes to reflect on the fact that the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass is not simply a prayer of devotion in the manner of our Rosary or our Novenas or our other devotions. Every word, every gesture, has a theological meaning and an historical context, which is why it's incumbent upon priests and lay people alike to offer the Holy Sacrifice with precise attention to detail and not casually. For example, there are specific points in the Mass where the priest extends his hands. This act symbolizes the priest collecting the prayers of the congregation and sending them upward toward heaven, but it is a specifically priestly gesture. You'll notice that when a Deacon reads the Gospel, when he says, “The Lord be with you,” he does not extend his hands; he's not allowed to, because he's not a priest. Deacons can do a lot of things: they can baptize people, they can perform weddings, they can bless religious articles, they can even give Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, but they can't extend their hands in public prayer because they are not priests. Somehow along the way the custom developed of lay people holding up their hands during the praying of the Lord’s Prayer before Communion, and I will never give up my efforts to convince them not to; but, what’s even worse is when the laity make a priestly gesture when responding to the priest, when they say, “And with your spirit.” I don’t know how that started, but I can’t believe it was a priest who told people to do that. What we do when we pray on our own is our own business; but, when we're celebrating the sacred liturgy, we don't do what's meaningful to us; we do what has been handed down to us over the centuries.

In the old days, we were taught in our catechism that the Mass was kind of like a time machine: the Sacrifice only appears to be offered here and now; in reality, it was only offered once on the Cross, and we are made present to it, and participate in it, by means of a miracle that transcends time and space. And that's very true.

So, let's consider our Blessed Lord's faithful participation in the liturgy of His day, as recounted for us today by Saiant Luke. Of course, the synagogue service in Nazareth was nothing compared to the real Sacrifice of our Lord's Sacred Body and Precious Blood, which he would offer for the Apostles at the Last Supper, and ratify for all of us with His death on the cross. But if our Lord felt it was important enough to faithfully adhere to a service that was only a symbol, how much greater attention should we give to one that is real?

* The holy King of Hungary, now regarded as the patron saint of his country, consecrated his kingdom to the Mother of God, converted his people to Christianity, overcame his enemies with kindness, and died famous for his charity and justice in the year 1038.

|