Are You a Closet Methodist?

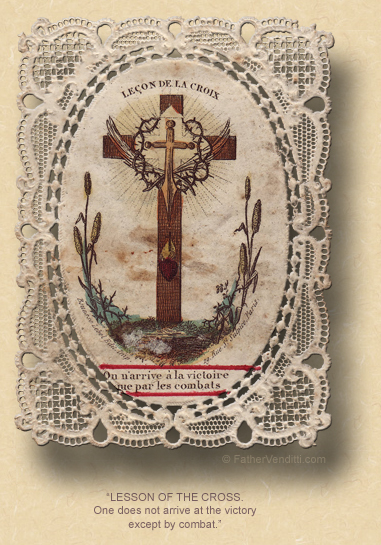

The Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross.

Lessons from the proper, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Numbers 21: 4-9.

• Psalm 78: 1-2, 34-38.

• Philippians 2: 6-11.

• John 3: 13-17.

The Second Class Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross.

Lessons from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Philippians 2: 5-11.

• Philippians 2: 8-9 (in place of the Gradual Psalm).

• John 12: 31-36.

The Solemn Holy Day of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross.

Lessons from the menaion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• I Corinthians 1: 18-24.

• John 19: 6-11, 13-20, 25-28, 30-35.

FatherVenditti.com

|

12:53 PM 9/14/2015 — We celebrate the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross by reading a Gospel verse with which we are all familiar. Some of you are old enough to remember watching a baseball game on television and seeing a man seated behind home plate wearing a rainbow wig and holding up a sign which said, “John 3: 16.” Well, this is that verse: “God so loved the world, that he gave up his only-begotten Son, so that those who believe in him may not perish, but have eternal life” (Knox), the linchpin, if you will, of Protestant theology, so forcefully preached by that great American evangelist, John Wesley. He was an Anglican layman, born in England, who set out to reform the Church of England from within, but unintentionally ended up founding his own religion, which today is known as the Methodist Church. He died in the United States in 1792. 12:53 PM 9/14/2015 — We celebrate the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross by reading a Gospel verse with which we are all familiar. Some of you are old enough to remember watching a baseball game on television and seeing a man seated behind home plate wearing a rainbow wig and holding up a sign which said, “John 3: 16.” Well, this is that verse: “God so loved the world, that he gave up his only-begotten Son, so that those who believe in him may not perish, but have eternal life” (Knox), the linchpin, if you will, of Protestant theology, so forcefully preached by that great American evangelist, John Wesley. He was an Anglican layman, born in England, who set out to reform the Church of England from within, but unintentionally ended up founding his own religion, which today is known as the Methodist Church. He died in the United States in 1792.

Wesley’s particular contribution to the history of American Protestantism was an institution that continues to this day, called the Revival. You’ve seen them before on television. Billy Graham was a big proponent of the revival. It can take various forms, but the one part of the revival which never changes is when everyone comes forward with their hands raised up declaring they are saved. And how can someone declare himself to be saved? Because, in John 3: 16 Jesus says that all you have to do is believe in Him and you’re saved. Nothing else is required. No sacraments. No priests. No Eucharist. No confession. Nothing. Just declare your faith in Jesus, and you’re going to heaven. It’s a classic example of Protestants doing what they do best: taking an isolated verse of Scripture totally out of context, and turning it into a maxim of dogma all by itself; which, of course, it not how the Bible is meant to be read.

So, what is our Lord saying, and why do we read it on the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross? Well, if you look at the whole passage in which this central verse about faith is contained, Jesus is trying to explain to Nicodemus that the salvation of mankind will come about when the Son of Man, which is how our Lord refers to Himself, is lifted up for all to see, just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the desert. Our Lord is referring to an event which takes place in the Book of Numbers (21: 1-9), which forms our first lesson today: when the Israelites were wandering in the desert, they were bitten by poisonous snakes as a punishment for grumbling against God; and, God told Moses that if he made a bronze snake and lifted it up on a pole, anyone who looked at it would be saved. But our Lord points out that the snake that Moses lifted up could only cure the people of a physical illness. They still had to be cured of the spiritual illness of sin. And that is to be done not by lifting up a snake on a pole, but by lifting up a man on a poll—a man who is also God. What our Lord is trying to explain to Nicodemus is that salvation will come from the cross. And this is the context of that famous verse about faith so loved by the Protestants, and yet so misunderstood by them:

And this Son of Man must be lifted up, as the serpent was lifted up by Moses in the wilderness; so that those who believe in him may not perish, but have eternal life. God so loved the world, that he gave up his only-begotten Son, so that those who believe in him may not perish, but have eternal life. When God sent his Son into the world, it was not to reject the world, but so that the world might find salvation through him (3: 14-17 Knox).

And that's where our Gospel lesson today ends; but, right after this, our Lord goes on …

For the man who believes in him, there is no rejection; [but,] the man who does not believe is already rejected; he has not found faith in the name of God’s only-begotten Son. Rejection lies in this, that when the light came into the world men preferred darkness to light; preferred it, because their doings were evil. Anyone who acts shamefully hates the light, will not come into the light, for fear that his doings will be found out. Whereas the man whose life is true comes to the light, so that his deeds may be seen for what they are, deeds done in God (vs. 18-21 Knox).

Did you ever see a Dracula movie? When you first see Dracula in a movie, who is he? He's this suave, sophisticated man about town, slicked back hair, always dressed to the teeth, seducing impressionable women with his perfectly polished charm;* but, he never walks in front of mirrors, he never comes out in the daylight, because if he did, who he really is would be exposed. He makes darkness his home to perpetuate the illusion of being just like everyone else. And in the Church of Jesus Christ we have many spiritual “Draculas”: men and women who go through the motions expected of them as members of the Church, but they have some secret, some dark room in their hearts where the light is never turned on and where the curtains are always drawn lest anyone see inside. Did you ever see a Dracula movie? When you first see Dracula in a movie, who is he? He's this suave, sophisticated man about town, slicked back hair, always dressed to the teeth, seducing impressionable women with his perfectly polished charm;* but, he never walks in front of mirrors, he never comes out in the daylight, because if he did, who he really is would be exposed. He makes darkness his home to perpetuate the illusion of being just like everyone else. And in the Church of Jesus Christ we have many spiritual “Draculas”: men and women who go through the motions expected of them as members of the Church, but they have some secret, some dark room in their hearts where the light is never turned on and where the curtains are always drawn lest anyone see inside.

For example, when husband and wife make love, they close the blinds and lock the door, but not for any sinister reason. They hide what they're doing from prying eyes simply because it is something for themselves alone and is no one else’s business. But when a person is there with someone who is not his spouse, he closes the blinds and locks the door for a very different reason: not out of concern for modesty or privacy or the innocence of his children, but to hide what he knows is wrong. And so a part of his life must then be lived in “darkness.” He is, in fact, living two lives: one in the daylight and one in the darkness, struggling all his life through to keep the two from ever touching one another. And when, out of carelessness or spiritual fatigue, the two collide—as they usually do—he must suffer the embarrassment and the scandal that his secret life causes in the eyes of those who knew him in the light.

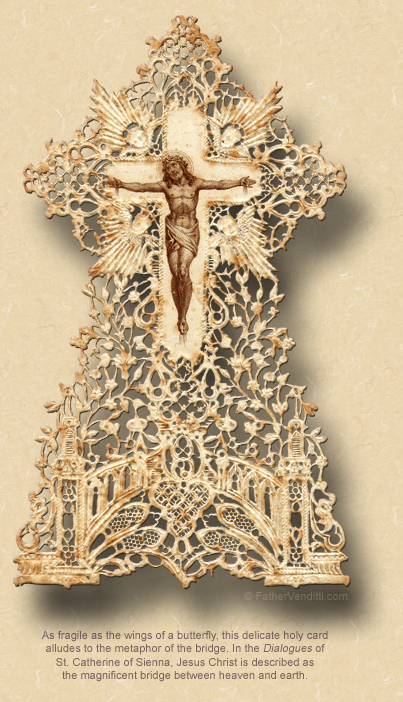

Right after this conversation between our Lord and Nicodemus the Gospel says that Jesus and His disciples then went to Judea where Jesus is Baptized by John, thus beginning His journey to the cross. The cross is the focus; from the beginning until the end of our Lord’s public life, the cross is the focus. What does it mean to “believe” in the Son of man as our Lord describes it here? It means to believe in the cross. Just as the Israelites believed in the snake on a pole, so we believe in the God on the pole. To stand in the shadow of the cross means to stand in the light, with your deeds clearly exposed, with nothing to hide, because of a life lived with God.

We are sometimes tempted to become Wesleyans or Methodists—not in fact, of course, but in belief—because we want to believe that saying it is enough. We show up on Sunday, sometimes; we go through the motions; we allow ourselves to be counted in some ecclesiastical head count. What more is required? Well, take out your Rosary and look at what's dangling from the end of it. Just gaze upon the Cross and you will see what more is required: not just saying it, but living it, like our Lord did when He gave His life.

"For God did not send His Son into the world to condemn the world, but that the world might be saved through him" (3: 17 NAB). And the world is saved through Him because He died on the cross to pay for our sins, so that we wouldn’t have to. But what that presupposes is that we’re now going to live as if we’ve been saved.

* Purely as an aside, note that this popular image of Dracula has its origin, not in Bram Stoker's ponderous, unreadable novel, but in the first of the stage plays, and later Tod Browning's 1931 Universal film based on it, both starring Bela Lugosi. The presentation of the vampire in the novel is somewhat of a cross between a man and an animal: unattractive, with hairy palms and face, exuding a foul odor, and certainly not perpetually dressed as a head waiter.

Misconceptions abound regarding Lugosi's seminal performance, in which he put his own indelible stamp on the role, completely reinventing the character created by Stoker. The play toured for several years in two companies, Lugosi taking the title role in the one covering the West Coast of the United States, contributing to his selection to play the movie role after the play premiered in Hollywood. It was, in fact, his first starring role on stage, as he was never the “Clark Gable of Hungary,” as often supposed. All of his roles in his native country were supporting ones, his claim to fame being rather as the organizer of the first labor union in Hungary (for actors), which led to his flight from Hungary after the Communist takeover.

Another misconception about Lugosi was the rumor that the halting, punctuated delivery of his lines in the film was due to reciting his lines phonetically because he didn't speak English. This may have been true when he first arrived in New Orleans and started working there; but, Lugosi had, in fact, worked on stage in the United States for a number of years prior to making the film, and knew the language well by then. Offered the role of the monster in Universal's second horror classic, James Whale's 1931 film, Frankenstein, Lugosi turned it down because it was not a speaking role and thought it beneath his talent level. The role instead went to an unknown stage actor named William Henry Pratt, whose stage name was Boris Karlof.

|