Can We Forgive Without Collecting Our Pound of Flesh?

The Twenty-Fourth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Exodus 32: 7-11, 13-14.

• Psalm 51: 3-4, 12-13, 17, 19.*

• I Timothy 1: 12-17.

• Luke 15: 1-32 (or 1-10).

The Seventeenth Sunday after Pentecost.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ephesians 4: 1-6.

• Psalm 32: 12, 6.

• Matthew 22: 34-46.

The Sunday before the Exaltation of the Holy Cross; a Postfestive Day of the Birth of the Theotokos; the Feast of Our Venerable Mother Theodora of Alexandria; and, the Feast of the Holy Bishop & Martyr Autonumous.**

First & third lessons from the pentecostarion, second & fourth from the menaion for the Venerable Mother, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Galatians 6: 11-18.

• Galatians 3: 23-29.

• John 3: 13-17.

• John 8: 3-11.

FatherVenditti.com

|

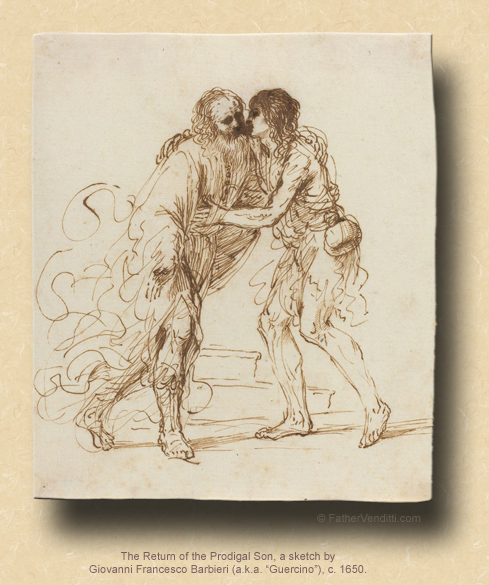

8:42 AM 9/11/2016 — Today’s Gospel lesson was a long one and, for that reason—and also because we had an enormously busy day here yesterday, from which I will be recovering for some time—I want to keep my homily brief. The lesson is actually a collection of parables told by our Blessed Lord, the very first one invoking the pleasing image of the Good Shepherd, which is always so dear to our hearts; but, the longest of them is the most familiar, I suppose: the parable of the Prodigal Son. It’s a story about forgiveness which is so familiar to us that we automatically assume we know what it means: the prodigal son returns and his father forgives him, illustrating the comforting fact God is ready to forgive us no matter how far we stray. That's a good third grade explanation of the parable, but it isn't sufficient because there are more than two characters in this story: there's a son who goes astray and a father who forgives him; but, there's also another son, and he's the one who's important. 8:42 AM 9/11/2016 — Today’s Gospel lesson was a long one and, for that reason—and also because we had an enormously busy day here yesterday, from which I will be recovering for some time—I want to keep my homily brief. The lesson is actually a collection of parables told by our Blessed Lord, the very first one invoking the pleasing image of the Good Shepherd, which is always so dear to our hearts; but, the longest of them is the most familiar, I suppose: the parable of the Prodigal Son. It’s a story about forgiveness which is so familiar to us that we automatically assume we know what it means: the prodigal son returns and his father forgives him, illustrating the comforting fact God is ready to forgive us no matter how far we stray. That's a good third grade explanation of the parable, but it isn't sufficient because there are more than two characters in this story: there's a son who goes astray and a father who forgives him; but, there's also another son, and he's the one who's important.

Every once in a while—especially here, where we hear so many confessions—a priest will run into people in confession who've been away from the Church for a long time, and it's often because something terrible happened to them and they decided to blame God: they lost a spouse or a child or had to suffer some terrible illness and this shook their faith in God as if, somehow, God let them down: "I lived a good life, so why would God let this happen to me?"

I always recommend them to read the book of Job, and many of you have heard me preach about it not too long ago, when we compared his story to that of his fellow prophet, Jonah. It begins by saying how there was no man in all the world more pleasing to God than Job, and how God allowed Job to be tested by Satan by having everything taken from him, including his children, and finally being afflicted with a horrible chronic illness. And his wife thinks he's crazy because he continues to praise and worship God. And Job's response to her is one of the most electrifying verses in the Bible: "Naked I came from my mother's womb, and naked shall I return; the Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord” (Job 1: 21 RSV).

Now, we don't see that kind of faith very often. Our faith is not unconditional like Job's. We put in the hours by living a good life, then we expect God to pay the wage—in spite of the fact that Jesus told us, on more than one occasion, that reward and punishment are not in this life, and that God allows it to “rain on the just and unjust alike.” But we ignore all of that. We still believe that God should reward us for our good life now, and if He doesn't then there's something wrong with Him.

And that's the real message of this parable. Yes, of course it is a story about forgiveness, and we should feel comforted by the fact that God is always willing to forgive as long as we are willing to repent. But there's a lot more to the story than that. We often overlook the fact that, in having the father in the story react the way he does to his elder son, Jesus has completely thrown out every notion of human justice there ever was.

We always overlook the older son in this story. We always focus on the younger son, the prodigal son; that’s why we call it “the Parable of the Prodigal Son.” But the older son is important, too. He goes to his father and makes two accusations: he accuses his brother of wasting his inheritance on loose women;—an accusation for which there is no evidence,  since the Gospel only says he ran out of money but doesn't say why—but, he also accuses his father of being unfair, and this accusation is true. In doing what he does for the prodigal son, the father has done a gross injustice to his elder son. since the Gospel only says he ran out of money but doesn't say why—but, he also accuses his father of being unfair, and this accusation is true. In doing what he does for the prodigal son, the father has done a gross injustice to his elder son.

And isn't the reaction of the older son exactly how we react to God when we think He's been unfair to us? We lose a loved one to death, for example—a child or a spouse or a parent—and we don't care that God has taken that person to Himself; we only care what we think He's done to us. Or we or someone we love is forced to suffer a long or painful illness. We don't care that He's given that person a great opportunity to avoid Purgatory by allowing them to sacrifice here on earth; we only want Him to be nice to us now.

We, of course, don't fault the father for his forgiveness because we know he represents God, and we like the idea of God always willing to forgive us no matter how wretched we've behaved; but, his manner of forgiveness is not typical, and highlights the fact that we often don't look at what he does in this parable closely enough, because the way the father chooses to forgive his younger son is actually very foreign to us. He doesn't scold him, nor does he offer his forgiveness conditionally, demanding an apology the way we usually do. We make ourselves feel better, pretending to be magnanimous by saying, “I forgive you,” but we always make sure to collect our pound of flesh in the process. Our forgiveness is really nothing more than a kind of emotional blackmail: “I forgive you, so long as you continue to feel guilty about it.” And you have to admit that, nine times out of ten, that's how we “forgive” anyone whom we feel has done us wrong. But the father in the parable doesn't do any of that; instead, he interrupts his son's apology and throws a party, pretending that the offense never took place, which only highlights the difference between the kind of forgiveness we so often offer to each other and the nature of God's forgiveness to us when we've sinned.

As a society, we've become obsessed with the whole concept of fairness, and as Americans we've been conditioned to frown upon any hint of injustice; and, this kind of thinking infects our relationship with God. The use of this familiar parable as the Gospel lesson of today's Mass gives us an opportunity to reflect on the fact that God doesn't deal with any of us according to the rules of human justice. God owes us nothing. And even if we live a perfect life of perfect virtue, God owes us nothing. Living the way God wants us to live is what we owe to God; and, to quote a line I've used many times before, salvation—which is the only goal of the Christian’s life—is not payment for services rendered.

Either by coincidence or Providence, today is nine-eleven, and the anniversary of the most horrible terrorist attack ever launched against our country; and, as we pray today for the victims of that tragedy—both those who died and the long-suffering loved ones they left behind—forgiveness and mercy need to permeate our thoughts and prayers. Let us pause to reflect, then, on what kind of conditions we may have placed on our love and worship of God, and be thankful for the fact that God has placed no such conditions on us, making forgiveness of our sins only a confession away.

* In the Greek Psalter, this would be Psalm 50, known throughout most of Christendom as the chief Penitential Psalm. It's designation here as Psalm 51 reflects the Roman Missal's use of the Hebrew Psalter in the ordinary form. As the quintessential prayer of repentance, it figures prominently in the liturgy of the Eastern Churches, particularly in the Byzantine Tradition, in which is is heard daily at Vespers, and recited silently by the priest in the Divine Liturgy when he initially incenses the Holy Table. In the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite, it is recited every Wednesday at Lauds, and every day during Lent.

** The life of Theodora of Alexandria is as controversial as it is unsubstantiated. Supposedly, she lived during the time of Emperor Zeno (474-491), and was married to a young nobleman of profound piety named Paphnutius. Having fallen into the sin of adultery, she sought to make penance by masquerading as a man and entering a monastery under the name of Theodore, spending the rest of her life in rigorous penance before passing on into eternal life. Most scholars don’t believe a word of it.

Autonomous, on the other hand, was certainly real. Born in Italy and a bishop of the Byzantine Tradition in that portion of the country evangelized from Constantinople through Albania, he fled the persecution of Licinius, settling in Bithynia where, because of his great zeal for the faith, he was seized by the pagans and put to death while in the very act of offering the Divine Liturgy. His actual feast is September 12th; but, because tomorrow is the Leave-Taking of the Birth of the Theotokos, the observance is transferred to today. He is particularly venerated in the Italo-Byzantine Catholic Church, sometimes called the Italo-Albenese Church.

Father Michael's family has its origins in the Italo-Byzantine Church, as do most whose ancestry spawns from the Albanian Gypsy migration into Italy in the 16th and 17th centuries. Though they identify as Gypsies, they are not ethnic Romanis, referring to themselves as "Gheigs," and their language, called "Gheigity" (the spelling is phonetic), has the distinction of the being the only existing language on the planet that is exclusively spoken, with no alphabet and no way to write it except phonetically; it shares common elements with Greek. Father Michael's grandfather was the last member of his family to speak this unwritten language.

The small Church's ranks swelled just prior to the First World War, when Albanian Orthodox, fleeing across the Adriatic into Italy to escape the genocide of the Turks against the Albanians, came into union with Rome and joined this Church. During the Second World War, Mussolini tried again to exterminate them. Though small today, consisting of a Metropolitan See and a single Suffragan See, it remains vibrant in Italy; but, most who came to the United States were absorbed into the Latin Church, there being no institutional structure of the Italo-Byzantine Church in this country (a parish once operating in Brooklyn, New York, closed some years ago); however, the Ruthenian Church in the United States maintains, by arrangement with the Holy See, a single parish of Italo-Byzantines in Las Vegas under the care of the Eparchy of Phoenix.

|