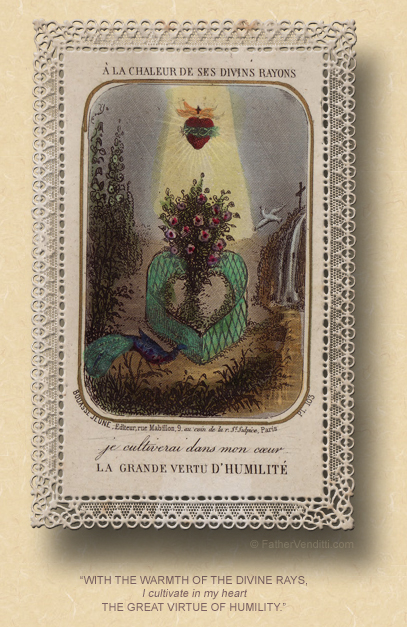

The True Nature of Humility.

The Twenty-Second Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Sirach 3: 17-18, 20, 28-29.

• Psalm 68: 4-7, 10-11.

• Hebrews 12: 18-19, 22-24.

• Luke 14: 1, 7-14.

The Twelfth Sunday after Pentecost.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• II Corinthians 3: 4-9.

• Psalm 33: 2-3.

• Luke 10: 23-37.

FatherVenditti.com

|

7:21 AM 9/2/2019 — You have to have noticed that the Scripture lessons of today’s Mass focus our attention on that one virtue which is the foundation of all others: the virtue of humility. It’s so necessary as the soil for the growth of every other Christian virtue that our Lord takes advantage of every opportunity He can find to explain it to his disciples. In the particular event recorded for us by Saint Luke today, He’s been invited to dinner at the home of one of the leading Pharisees, and He notices how the guests, as they arrive, are all jockeying for a better seat at the table, either closer to Him or to their host. It’s probably after everyone is seated and settled and started to dig into their shrimp cocktails that He tells them a parable. 7:21 AM 9/2/2019 — You have to have noticed that the Scripture lessons of today’s Mass focus our attention on that one virtue which is the foundation of all others: the virtue of humility. It’s so necessary as the soil for the growth of every other Christian virtue that our Lord takes advantage of every opportunity He can find to explain it to his disciples. In the particular event recorded for us by Saint Luke today, He’s been invited to dinner at the home of one of the leading Pharisees, and He notices how the guests, as they arrive, are all jockeying for a better seat at the table, either closer to Him or to their host. It’s probably after everyone is seated and settled and started to dig into their shrimp cocktails that He tells them a parable.

The parable He tells them is simple enough and, if we were to take it at face value, would rise no higher than the level of home-spun wisdom about how, in the long run, it’s always better to know your place and not be too ambitious. Centuries later, the spiritual doctors of the Church would identify ambition as a sub-set of the sin of pride, a disordered tendency to look for honor, to exercise authority, to have a position over others, to always think that those who have authority over us are less capable than we are. It’s a temptation in every walk of life, but especially in the Holy Priesthood, and every priest, I think, goes through a period in his life where he thinks his bishop, his dean, or anyone else appointed over him isn’t doing the job nearly as well as he could, and if everyone would just listen to him then life would be grand.

In the Ruthenian Catholic Church in which I used to serve, whenever one had the occasion to offer the Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil the Great, there is a part of the Eucharistic Prayer in which the priest prays to God saying, “We have done nothing good upon the earth,” and it’s true. Everything good in this world comes from God, and everything we might do that’s good is done by God working through us by means of Grace. It hearkens back to something said by Cardinal Ratzinger just a few months before he become pope: that the goal of the Christian life is to “get out of God’s way,” to submerge ourselves so that we become Christ living and acting through us, as John the Baptist said: “He must increase; I must decrease” (John 3: 20 NABRE).

So, the true nature of the virtue of humility has nothing to do with being shy or timid or mediocre; quite the contrary. True humility should cause us to recognize that whatever talents and abilities we have are given to us by God to be used in His service, and our possession of them should cause in us a profound sense of gratitude.  True humility doesn’t consist of staying passive and in the background, and those who interpret it that way usually end up accomplishing nothing for God. At the same time, true humility always prompts us to self-examination, which is why true humility only becomes authentic when it is tempered and nourished frequently in the confessional. True humility doesn’t consist of staying passive and in the background, and those who interpret it that way usually end up accomplishing nothing for God. At the same time, true humility always prompts us to self-examination, which is why true humility only becomes authentic when it is tempered and nourished frequently in the confessional.

In his Introduction to the Devout Life, Saint Francis de Sales provides us with a striking image: he describes us all as mules, and goes on to say that the mule is a disgusting beast. And then he says, “Alas! Do mules cease to be disgusting beasts simply because they are laden with precious and perfumed goods of the prince?” (Introduction to the Devout Life, III, 5). The parallel he makes between man’s life and beasts of burden is very valid, and echos the words of the Psalmist:

I was all dumbness, I was all ignorance, standing there like a brute beast in thy presence. Yet ever thou art at my side, ever holdest me by my right hand. Thine to guide me with thy counsel, thine to welcome me into glory at last. What else does heaven hold for me, but thyself? What charm for me has earth, here at thy side? What though flesh of mine, heart of mine, should waste away? Still God will be my heart’s stronghold, eternally my inheritance (Psalm 73: 22-26 Knox).*

And there you have the paradox and the challenge of practicing the virtue of humility: God has given each of us talents and abilities to do many great things. We have no right to submerge them, since God has given them to us for a purpose. The danger is that when, as God’s mules, we are given a sack of precious jewels and treasures to carry behind the prince, we make the mistake of thinking that the treasure is ours and that we earned it somehow, when our job is nothing more than to deliver the cargo where directed. Think back to our Lord at the Pharisee’s dinner party, watching His fellow guests jockey for the best seats at table. Do we think that, because we’ve got a seat closer to the host, we’re going to get a better shrimp cocktail? Personally, I like to sit far away from the center of the action, because there’s always someone else just as unimportant as me who was supposed to sit there and didn’t show up, then I can eat his shrimp cocktail, too.

The bottom line is that the humble soul is constantly on the watch for the Will of God, whereas the proud soul has eyes only for its own way, its own preferences, its own ambition, its own achievements and aims, thus closing the door to God’s Grace. It doesn’t realize it because everything it sees is through its own backward-looking gaze, always concerned for how it appears. Like Saint Paul says,

God chose the lowly and despised of the world, those who count for nothing, to reduce to nothing those who are something, so that no human being might boast before God … so that, as it is written, “Whoever boasts, should boast in the Lord” (I Cor. 1: 28-29, 31 NABRE).

* In translations based on the Hebrew Psalter, this would be Psalm 72. Msgr. Knox’s translation is based on the Greek.

|