Launch Out Into the Deep.

The Twenty-Second Thursday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the secondary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Corinthians 3: 18-23.

• Psalm 24: 1-6.

• Luke 5: 1-11.

The Fourteenth Thursday after Pentecost; the Commemoration of Saint Giles, Abbot; and, the Commemoration of the Twelve Holy Brothers, Martyrs.*

Lessons from the dominica,** according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Galatians 5: 16-24.

• Psalm 117: 8-9.

• Matthew 6: 24-33.

|

If a Mass for the commemoration of the Abbot is taken, lessons from the common "Os justi…" of a Holy Abbot:

• Ecclesiasticus 45: 1-6.

• Psalm 20: 4-5.

• Matthew 19: 27-29.

|

|

If a Mass for the commemoration of the Martyrs is taken, lessons from the Mass Clamavérunt…," as on the commemoration of St. Symphorosa & Her Sons, of July 18th:

• Hebrews 11: 33-39.

• Psalm 132: 1-2.

• Luke 12: 1-8.

|

The Fifteenth Thursday after Pentecost; the Beginning of the Church Year, 7525 in the Byzantine Rockoning; the Feast of Our Venerable Father Simeon the Stylite & His Mother; the Synaxis of the Most Holy Mother of God of Miasena; the Feast of the Holy Martyr Aeithalas; the Feast of the Holy Women Martyred with Their Instructor, Ammon the Deacon; the Feast of the Holy Martyr Callista & Her Two Brothers, Evod & Hermogenes; and, the Feast of the Just Joshua, Son of Nun.***

First & fourth lessons from the pentecostarion, second & fifth from the menaion for the New Year, third & sixth from the menaion for the Stylite, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Ephesians 1: 1-9.

• I Timothy 2: 1-7.

• Colossians 3: 12-16.

• Mark 7: 24-30.

• Luke 4: 16-22.

• Matthew 11: 27-30.

FatherVenditti.com

|

9:02 AM 9/1/2016 — While you might think from the outset that we’re taking a break from the Blessed Apostle Paul’s yelling and screaming at the Corinthians, we’re not, really. 9:02 AM 9/1/2016 — While you might think from the outset that we’re taking a break from the Blessed Apostle Paul’s yelling and screaming at the Corinthians, we’re not, really.

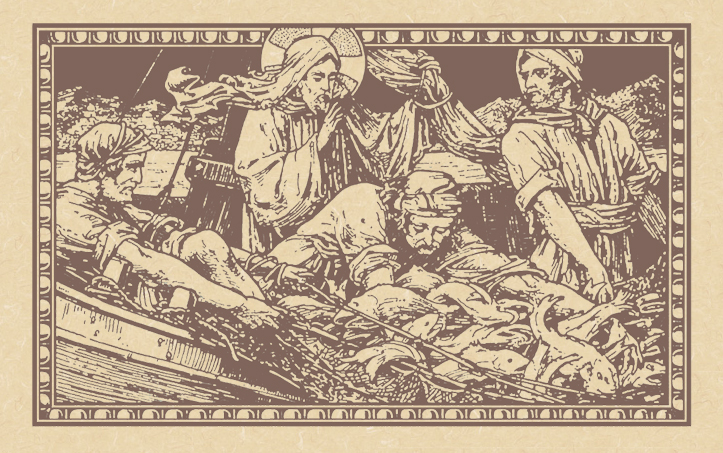

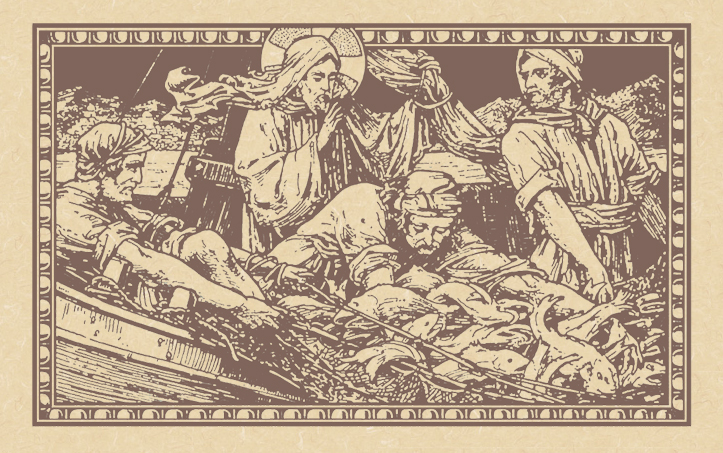

But we begin today with our lesson from Saint Luke’s Gospel, which you “old timers” will recall usually causes me to launch—no pun intended—into a retrospective of the life of Blessed John Henry Newman, whom you already know is one of my favorite saints. His Stations of the Cross were in the rotation of the sets we used on Fridays during Lent, though they weren’t that popular with most of you; I chalk that up to your lack of appreciation for Newman’s cultured Victorian prose.

Born into an Evangelical Christian family, Newman was later ordained a priest of the Church of England, served as pastor of the university parish at Oxford where he translated and studied the Fathers of the Church, was a principle leader of the "Oxford Movement" (an attempt to "catholicize" the Anglican Church in light of the teachings of the Fathers), and finally became a Catholic. He was so well regarded in his own country that, when he died, the London Times had a bigger spread for him than they had for Queen Victoria just a few years before.

When Newman was in his 20’s—around 1830 or so—he made a trip to Italy to see the Catholic Church there. The practice of the Catholic Faith was still restricted in England at the time; and, being a religious man, he wanted to see first hand what it was like. What he saw there horrified him: statues, the veneration of relics, a faith which he thought to be very far removed from the Bible-oriented faith of his youth.

On the trip back, the boat he was riding was becalmed in the Mediterranean for several weeks. He became ill with fever, and began to think about where his life was taking him. Because of his study of the Fathers, he no longer could believe that his own Church of England was the true faith, but he didn't know what was. It was there, on that boat, that he wrote his most famous hymn, which is still sung today in many Protestant churches:

Lead, Kindly Light, amid the encircling gloom—

Lead Thou me on!

The night is dark, and I am far from home—

Lead Thou me on!

Keep Thou my feet; I do not ask to see

The distant scene—

One step enough for me.

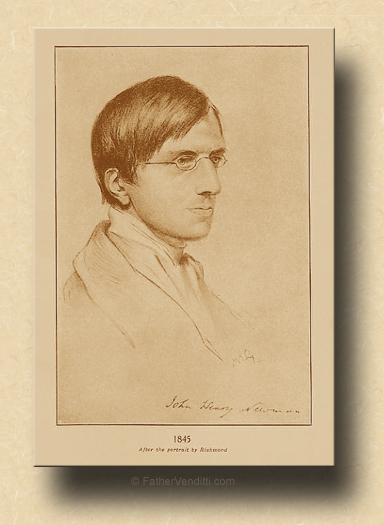

Now, if you had been able to go back in your time machine and talk to Newman at that point, and if you had told him that he would die a Cardinal of the Roman Church and a defender of the Catholic Faith, he probably would have committed suicide. But that's exactly what happened. And when he was in his eighties, just a few years before he died, he looked back on his life, and expressed his thoughts in an epic poem called The Dream of Gerontius, a dramatic portrayal of death and judgment, part of which became another famous hymn, which is still sometimes sung in Roman Catholic churches:

Praise the to Holiest in the Height,

And in the Depth be praised:

In all his works most wonderful;

Most sure in all His ways!

When I was studying at Villanova University I had an English professor who said that the last line of that stanza was the most perfect use of an adjective in the English language he had ever seen, when Newman said that God was “Most sure in all His Ways!” He could look back on his life, on all the changes he had been through, and all the pain that they caused, and see them as part of a deliberate plan on the part of God to bring him to where he now stood. And yet, during all those difficult years of uncertainty and confusion, God never once revealed to him where He was taking him, or even gave him a hint about it, but rather required him to have faith that He was, indeed, “Most sure in all His ways!” When I was studying at Villanova University I had an English professor who said that the last line of that stanza was the most perfect use of an adjective in the English language he had ever seen, when Newman said that God was “Most sure in all His Ways!” He could look back on his life, on all the changes he had been through, and all the pain that they caused, and see them as part of a deliberate plan on the part of God to bring him to where he now stood. And yet, during all those difficult years of uncertainty and confusion, God never once revealed to him where He was taking him, or even gave him a hint about it, but rather required him to have faith that He was, indeed, “Most sure in all His ways!”

Peter must have felt the same kind of thing in the event which is described in our Gospel lesson for today. Jesus knew from the beginning what Peter would eventually be and what role he would play in establishing the Church, but Peter didn't know it. Peter had to grow first. And Jesus took him through it, deliberately and painfully, “Most sure in all His ways!” But He knows that Peter is confused and hurting about it, and wants to console him in a cryptic way without revealing the answers, as He so often does; so after He's finished preaching to the crowds, He rows out with Peter into the lake, and utters some of the most electrifying words in all Scripture: "Launch out into the deep, and throw out your nets." And Peter reacts the way all of us would: "What's the point? There's no fish out here. We've been at it all night and haven't caught a thing!" And Jesus just says, "Launch out into the deep.”

And the miraculous catch of fish that Peter makes is a symbol, intended for us as well as for him. No! We don't know what's going on. We don't know where we're going, or perhaps even where we've been. But Jesus does. It's part of His plan. And believing that means, first of all, letting “one step” be enough, and then, allowing Him to be “Most sure in all His ways!” And that's why Peter's reaction to this strange command is important for us. He says, "We've worked hard all night, and caught nothing; but, because You say so, I will let down the nets." Not because I agree, not because I understand, not because I'm not concerned, not because I think You're right, but only because I trust You—because You say so. That's enough. And that's why Peter passes the test of an Apostle.

Now, officially we are told that the cycles of Epistles and Gospels for ferial day Masses are random and not meant to necessarily go together so that the priest has different subjects on which to preach should he choose to do so. If so, than God’s Providence was surely at work today; for, while today’s Apostolic lesson from First Corinthians continues the theme the Apostle was on about yesterday—regarding the factions claiming allegiance to Paul and Apollo—coupled with the Gospel lesson we just heard, it seems like the flip side of an old record.  I may have been premature yesterday when I told you that Paul was done whining about the Athenians, because he does get another dig in today when he goes on—one more time, if you please—about the foolishness of worldly wisdom, this time quoting from the Book of Job (Job 5: 13); yesterday is was Jeremiah, so he’s pulling out all the stops. And today’s lesson is really the conclusion of yesterday’s dressing-down about the factions that had arisen in Corinth among those who preferred him to his friend and successor, Apollo, and vis-à-vis. They’re not supposed to be following Apollo; they’re not supposed to be following Paul; they’re supposed to be following Christ: I may have been premature yesterday when I told you that Paul was done whining about the Athenians, because he does get another dig in today when he goes on—one more time, if you please—about the foolishness of worldly wisdom, this time quoting from the Book of Job (Job 5: 13); yesterday is was Jeremiah, so he’s pulling out all the stops. And today’s lesson is really the conclusion of yesterday’s dressing-down about the factions that had arisen in Corinth among those who preferred him to his friend and successor, Apollo, and vis-à-vis. They’re not supposed to be following Apollo; they’re not supposed to be following Paul; they’re supposed to be following Christ:

Everything is for you, whether it be Paul, or Apollo, or Cephas, or the world, or life, or death, or the present, or the future; it is all for you, and you for Christ, and Christ for God (I Cor. 3: 22-23 Knox).

But you’ll notice that there’s a third name added there. Yesterday it was Paul and Apollo, but today he adds the name Cephas to that list; and, I’m sure I don’t have to remind you that Cephas is the Greek form of Petras or Peter in Latin. Why is he suddenly dragging Peter into all this? You may recall, from yesterday’s homily, that Paul was constantly battling with rouge Christian missionaries who were following him around and trying to undo all his conversions on the pretext that one had to first become a Jew in order to be baptized a Christian, and Paul had appealed to Peter to correct them, which he did, but that Peter’s decree authorizing Paul to baptize the Gentiles without circumcision was largely ignored by these people. Today, in his conclusion to the scolding of the Corinthian Christians for allowing themselves to be divided because of their human allegiances—some to Paul and some to Apollo—he also says that they shouldn’t even be devoted to Peter, that their allegiance should be to Christ.

I have to be cautious how I say this, but during the time every day that I’m in the confessional before Mass, while you all are saying the Rosary, there isn’t a day that doesn’t go by that someone doesn’t confesses that he or she is confused and even angry at our Holy Father; and, unless you’ve been asleep the last few days, when we’ve discussed the Apostle Paul’s reflections on what he did in Athens and how it had backfired on him, and how his mistake in Athens is analogous to the modern Church trying to ingratiate herself to the editorial page of the New York Times—the whole idea of embracing secular causes like global warming or migrants or whatever and how it never bodes well for the cause of Christ and only ends up confusing and hurting people in the long run—there’s a certain irony in the Apostle’s inclusion of Peter here.

Which takes us back to our Gospel lesson, the high point of which is when Peter falls on his knees before our Lord and says, “Depart from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man” (Luke 5: 8 RM3). Everyone’s life is filled with uncertainty of some kind. Some of us are uncertain about our health, some about where the next pay check is coming from, some about their financial condition, or maybe about a relationship, or perhaps even some crisis of faith; and, some of us are unsettled and unsure even about things the Holy Father is saying and doing. For everyone the future is dark at some point. And that uncertainty is not easy to live with, and it can try our faith tremendously. We don't know, sometimes, what the Lord is doing to us, or why. But He understands that, and He commands us to "launch out into the deep.” And the test of Christian maturity is to have enough faith to believe that, even if we don’t know where we’re going, Christ does, because He is “Most sure in all his ways!”

* Giles, an Athenian by birth, lived most of his life in the south of France as a hermit in a vast forest. He was persuaded by King Theodoric to found a monastery, and became so famous for his miracles that a great number of Churches were dedicated to him after his death, which occured in sixth century.

Not much is known of the "Twelve Holy Brothers" except that they were natives of Africa who were all martyred together in Beneventura, Italy, under the Emperor Valerian in the year 258.

Various editions of the Missal of St. John XXIII are in disagreement as to how the multiple commemorations on this day should be handled. Some clearly indicate that the commemoration of the Abbot is taken only by an additional Collect, Secret and Postcommunion added to the ferial day Mass, but (for some unexplained reason) allowing a Mass for the commemoration of the Martyrs; however, this web site conforms to the general rubrics of that Missal, in which a Mass for either commemoration could be taken outside of any privileged season.

** In the extraordinary form, on the ferial days outside of privileged seasons, the lessons are repeated from the previous Sunday.

*** Sept. 1st constitutes the most convoluted assemblage of feasts on the calendar of the Byzantine Churches. The typicon of the Ruthenian Church of the USA, in a lingering bow to Latinization, allows for one to be chosen among them, but this web site conforms to the more traditional Byzantine practice of observing all of them.

In Constantinople, the New Year began originally on September 1st. Called the “Indiction,” it began a cycle of fifteen years which began in 312 under Constantine the Great, the date for the beginning of the liturgical year being the Emperor’s birthday.

Simeon the Stylite was born near Antioch. He was a shepherd in his youth, then entered a monastery where he spent ten years as a holy monk. In order to enjoy complete silence and solitude for the sake of contemplation, he embraced the heremitical life, spending the rest of his days in worship and prayer on top of an isolated tower, hence the title “Stylite,” which means “of the column.” He went on to eternal life in the year 459. A monastery was built close to the column or tower, whose walls my still be seen near Aleppo, Syria, where it is known as the “Fortress of St. Simeon.”

The Synaxis on this day is in honor of a particular icon of the Theotokos which is said to be miraculous. In the days of the Iconoclasts, it was thrown into a river and recovered several years later. It was then transferred to the monastery of Miasenes, near Melitene in Armenia, where is is still venerated.

Aeithalas was martyred in Persia in the year 355.

The Forty Holy Women were martyred in Greece in the year 321 or 323 under Emperor Licinus. Ammon was their instructor in the faith.

Joshua was Moses’ companion, and succeeded him in leading the people of Israel into the promised land after taking the town of Jericho, dividing this land among the twelve tribes of Israel, thus setting the stage for the rest of the Old Testament and creating the Holy Land known to our Blessed Lord.

|