Excedrin Headache Number Four: Saints Who Write Textbooks; and, What on Earth is God Up To?

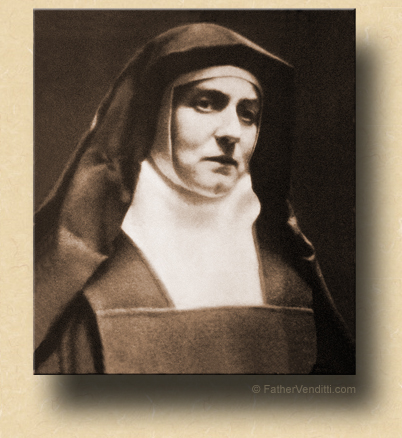

The Eighteenth Wednesday of Ordinary Time; or, the Memorial of Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross.

Lessons from the primary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Numbers 13: 1-2, 25--14: 1, 26-29, 34-34.

• Psalm 106: 6-7, 13-14, 21-23.

• Matthew 15: 21-28.

|

…or, any lessons from the common of Martyrs for a Virgin Martyr, or the common of Virgins for One Virgin.

|

The Third Class Vigil of Saint Lawrence, Martyr; and, the Commemoration of Saint Romanus, Martyr.*

Lessons from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ecclesiasticus 51: 1-8, 12.

• Psalm 111: 9, 12.

• Matthew 16: 24-27.

The Ninth Wednesday after Pentecost; a Postfestive Day of the Transfiguration; and, the Feast of the Holy Apostle Matthias.

First & third lessons from the menaion for the Apostle, second & fourth from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Acts 1: 12-17, 20-26.

• I Corinthinans 16: 4-12.

• Luke 9: 1-6.

• Matthew 21: 28-32.

FatherVenditti.com

|

10:13 AM 8/9/2017 — Today is not only the memorial of Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, it is also the 75th anniversary of the martyrdom of this brilliant philosopher and professor of philosophy known more popularly by her birth name, Edith Stein. She was born in 1891 to Jewish parents in Breslau, Germany, which is now part of Poland. She studied philosophy under Husserl, who was the father—more or less—of a philosophical school of thought known as phenomenology. Husserl also had a profound influence on a young Karol Wojtyła, who, like Saint Teresa Benedicta, was also a professor of philosophy. Inspired by the writings of Saint Teresa of Avila, she was baptized on January 1st, 1922, and went on to teach philosophy at several Catholic universities in Germany from 1923 through 1933 until forced to resign due to antisemitic legislation. The very year she resigned her professorship, she entered the Discalced Carmelite convent in Cologne, where she received her religious name of Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. Toward the end of 1939, she was transferred to the convent at Echt, Holland, on account of the Nazi persecution of the Jews; but, in 1942, when Germany occupied the Netherlands, she was arrested and sent to Auschwitz, which is where she met her death. 10:13 AM 8/9/2017 — Today is not only the memorial of Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, it is also the 75th anniversary of the martyrdom of this brilliant philosopher and professor of philosophy known more popularly by her birth name, Edith Stein. She was born in 1891 to Jewish parents in Breslau, Germany, which is now part of Poland. She studied philosophy under Husserl, who was the father—more or less—of a philosophical school of thought known as phenomenology. Husserl also had a profound influence on a young Karol Wojtyła, who, like Saint Teresa Benedicta, was also a professor of philosophy. Inspired by the writings of Saint Teresa of Avila, she was baptized on January 1st, 1922, and went on to teach philosophy at several Catholic universities in Germany from 1923 through 1933 until forced to resign due to antisemitic legislation. The very year she resigned her professorship, she entered the Discalced Carmelite convent in Cologne, where she received her religious name of Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. Toward the end of 1939, she was transferred to the convent at Echt, Holland, on account of the Nazi persecution of the Jews; but, in 1942, when Germany occupied the Netherlands, she was arrested and sent to Auschwitz, which is where she met her death.

My undergraduate degree is in philosophy, so I'm familiar with some of her writings, and they are thick going, the kind of books you have to read with a bottle of Excedrin next you just to keep your head from exploding.

Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross was canonized and declared a martyr—no surprise—by fellow author of philosophy textbooks, Pope Saint John Paul II, who also declared her co-patroness of Europe, along with Saint Bridget of Sweden and Saint Catherine of Siena.

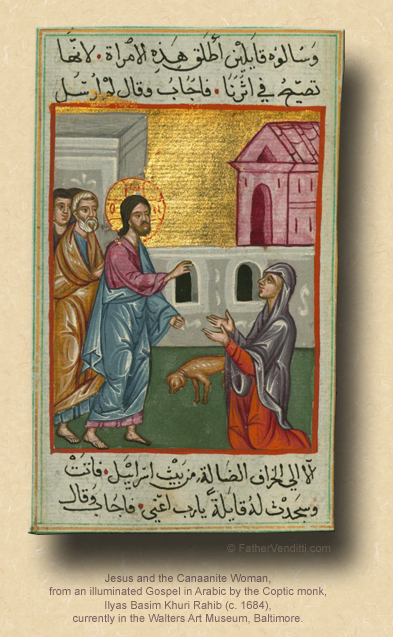

Today’s Gospel lesson is another of those which bludgeons us with an inconvenient truth; for, in it, our Blessed Lord is approached by a woman who is drawn to Him solely by faith, seeking nothing for herself, but begging Him to help her tormented daughter. He ignores her, so the Gospel tell us; but, she's so persistent in her pursuit of our Lord that the disciples ask Him to “Rid us of her…, she is following us with her cries” (Matt. 15: 23 Knox). He turns to her and says, “My errand is only to the lost sheep that are of the house of Israel” (v. 24 Knox). In other words, “I'm not going to help you; you're not even a Jew.” And I'm sure you're waiting with baited breath for me to explain to you how our Lord isn't really saying what He seems to be saying, and how this is all the result of some inferior translation.

But there's nothing wrong with this translation. He appears to be rude to this poor woman because He is. He seems to be telling her that, because she's not of the same nationality as He, He's not interested in her problem because that, in fact, is what He's telling her. There is no mistake. He even goes so far as to get personally abusive, telling her, “It is not right to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs” (v. 26 Knox); and, if you're a woman who's ever been called a dog by a man, I can only guess what that must feel like.

Of course, there is a method in our Lord's madness which has deep implications for our interior life, and we'll get to that in a moment; but, consider first how this poor woman reacts to this very brazen insult: "Yes, Lord, yet even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters' table" (v. 27 RSV). Now, I don't think there's a woman here who, if they went to a man for help, and he responded by calling her a dog, wouldn't just haul off and slap him silly; but, remember, this woman is desperate. Saint Anselm tells us, in one of his homilies (cf. Golden Chain, MT-MK 4521), that it's clear from the text that this woman clearly believed that Jesus was God, something that most of the Jews with our Lord that day probably didn't yet realize. Keep in mind, too, that she's a Canaanite.  The Canaanite's were a race of people who had been Jews, but had abandoned the faith and fallen into apostasy, so the Jews threw them out of Israel so as not to be corrupted by them. She's sneaked back across the border for the sole purpose of asking our Lord to help her tormented daughter; she doesn't even want anything for herself. And unless you’ve lived most of your life under a rock, you’ll know from experience that desperation has a way of tearing down the walls of pride. She's come there with a mission, and she's not about to let anything derail her from it, even if it means she has to swallow her pride and take an insult without responding to it. The Canaanite's were a race of people who had been Jews, but had abandoned the faith and fallen into apostasy, so the Jews threw them out of Israel so as not to be corrupted by them. She's sneaked back across the border for the sole purpose of asking our Lord to help her tormented daughter; she doesn't even want anything for herself. And unless you’ve lived most of your life under a rock, you’ll know from experience that desperation has a way of tearing down the walls of pride. She's come there with a mission, and she's not about to let anything derail her from it, even if it means she has to swallow her pride and take an insult without responding to it.

And here is where we are able to deduce the method in our Lord's madness. He's not so much testing her;—as Saint Anselm told us, she already believes He's God, and He knows this, so He doesn't need to test her faith—but, she does need to be instructed as to why she's doing what she's doing. She's gone there because—as we've said three times now—she's desperate. Her daughter is suffering, she knows that Jesus is in a particular place at a particular time, so she's off. She's not even thinking clearly. By treating her the way He does initially, our Lord forces her to put the breaks on and think about what she's doing, not because there's anything wrong with what she's doing, but because he wants her to understand her own actions: Tunc respondens Jesus, ait illi: O mulier, magna est fides tua: fiat tibi sicut vis. “And at that Jesus answered her, ‘Woman, for this great faith of thine, let thy will be granted’” (v. 28 Knox). She had no idea that she was acting out of faith, but now she does, and so do the disciples who had initially begged Him to send her away; so, what we have in this episode in the life of our Blessed Lord is just another example of what’s been presented to us on and off all summer: a lesson about the permissive will of God, and how God will often allow a cross or hardship to come our way as a means of enacting a change in us.

There is not a person here who hasn't suffered a tragedy or endured a hardship or borne a cross that hasn't caused us to wonder what on earth God is up to. Like the Canaanite woman, we are already people of faith, and so we ask, “Why is this happening? What have I done wrong?” The answer is that we've done nothing wrong; but, if God were to reveal to us the reason for our suffering, or show us his plan for us, then there would be no merit in the sacrifice. As we already observed in celebrating the memorials of many of the saints presented to us this time of year, when one sets out to serve the Lord, one doesn't do what one wants; one does what one is told. Saint Paul said it better:

O the depth of the riches of the wisdom and of the knowledge of God! How incomprehensible are his judgments, and how unsearchable his ways! For who hath known the mind of the Lord? Or who hath been his counsellor? (Rom. 11: 33-34 DRA).

* In the Roman Rite, the concept of a vigil differs completely between the ordinary and extraordinary forms. In the ordinary form, a vigil is simply a celebration of the feast the evening before, either prior to or following First Vespers. In the extraordinary form, the word “vigil” designates the entire day before a First or Second Class Feast, and the Mass on that day takes place in the morning, with the day of vigil having lessons of it's own.

St. Romanus was a Roman soldier who was converted by St. Lawrence. He was beaten and beheaded in the year 261. Because today's vigil is of the Third Class, a Mass for the commemoration is not permitted, with the commemoration being observed by an additional Collect, Secret and Postcommunion added to those of the Vigil.

|