The Blessed Eucharist: Who, Exactly, is Presuming to Feed Whom?

Lessons from cycle A of the Dominica, according to the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite:

Isaiah 55: 1-3.

Psalm 145: 8-9, 15-18.

Romans 8: 35, 37-39.

Matthew 14: 13-21.

The Eighteenth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

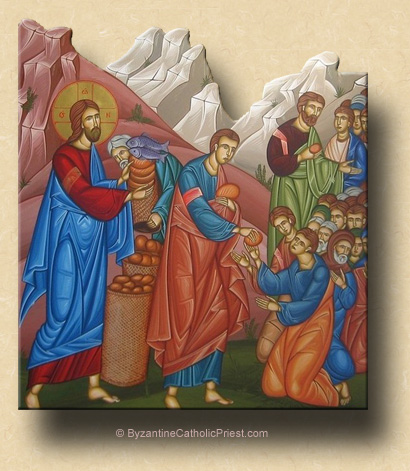

2:39 PM 8/3/2014 — If you can't figure out that the miracle of the loaves and fish is a prefiguring of the Holy Eucharist, you need some sort of remedial class. It’s painfully obvious that this event of feeding 5000 people with five pieces of bread and two fish has little to do with hunger or magic tricks as it does with feeding the world with the Body and Blood of Christ. 2:39 PM 8/3/2014 — If you can't figure out that the miracle of the loaves and fish is a prefiguring of the Holy Eucharist, you need some sort of remedial class. It’s painfully obvious that this event of feeding 5000 people with five pieces of bread and two fish has little to do with hunger or magic tricks as it does with feeding the world with the Body and Blood of Christ.

And there is the symbolism of the Holy Eucharist all over this passage. For example, when he gets out of the boat, the first thing he does is heal the sick. Why? Because in order to receive Holy Communion one must be free from sin.

When our Lord commands the disciples to feed the people with the meager supplies on hand, they complain that it won’t be enough; but our Lord presses them on, reminding them that what they are going to accomplish will be done by his power, not their own.

Then after he breaks the bread, he gives the bread and fish to the disciples to distribute to the people; he doesn’t distribute it himself. That’s because Christ entrusts the Holy Eucharist to his Church, particularly his priests, without whom there could be no Eucharist.

Then St. Matthew goes on to tell us that they all ate and were satisfied. Of course they were, because the Body and Blood of the Lord is not food in the conventional sense, but spiritual food—the actual life of the risen Savior. No ordinary food could satisfy that completely. And it wasn’t just some who were satisfied, nor even most: St. Matthew says that all were satisfied, because the Eucharist is the remedy for all sin, for all people.

And when it was all over, they took up twelve baskets of leftovers, in much the same way that we keep “leftover” particles of the Blessed Eucharist in our tabernacles in church. And the baskets are left over because the Eucharist, once we partake of it, cannot remain dormant within us, but must be carried with us into the world, so that the life of Christ which we receive can be shared with everybody.

And when the baskets are collected, Jesus and his disciples get back into the boat and move on, because the grace of the Eucharist must be spread to everyone. No one can attain heaven without it, as our Lord himself said in Chapter Six of John’s Gospel, "…you can have no life in yourselves, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man, and drink his blood" (6: 54).

Of course, our Lord’s disciples were not thinking of these things when our Lord performed this miracle—and he did it twice; they were probably thinking, “Gee, what a great trick. Wish I could do a trick like that.” Whether they remembered it on the night of the Last Supper we’ll never know. But they certainly remembered it later, and so did the Fathers of the Church. St. Jerome, in the fourth century, wrote,

The multiplication extended itself beyond that which was necessary, so that twelve baskets remained, one for each Apostle. The Apostles had not yet received the power to consecrate and distribute the Bread of Heaven, the Eucharist; yet Jesus, with a symbolic act, to nourish the hungry crowd, did not create new food, but took that which was in the hands of his disciples, and blessed it.

It explains a great deal about the Holy Priesthood and the sacraments: the priest is necessary to perform the mysteries, but it’s the power of Christ that makes them happen. And even in our own individual lives, everything we do that’s good is done by the grace of God acting through us.

And given the fact that many of you have come here to celebrate “God Day,”—though it seems to me that every day is a God Day, so maybe I don't quite understand the nature of the celebration—it would be remiss of me not to mention the manner in which our Blessed Lord performs this miracle. Notice that there is no ceremony connected with it: he doesn't wave his arms about, he doesn't close his eyes and utter incantations, he doesn't hum or chant or do anything at all to indicate that anything out of the ordinary is happening. The Gospel tells us he blessed the bread, but there's nothing to indicate that the blessing was any different than that which would have been done at any meal. In other words, he says grace, gives the food to the disciples to distribute, and that's it. The miracle happens in a very quiet and muffled way, and makes all the more of an impression because of it; and, it causes me to lament how we display our lack of faith in the Blessed Eucharist whenever we succumb to the temptation to adorn Holy Mass with all manner of theatrical gimmicks: presentations, programs, cute performances by children, prayers of the faithful that go on forever in which we tell God what we think he should be doing based on our own social or political agendas. We add theater to the Sacred Liturgy of the Eucharist because we've ceased to believe in it: the Mass is no longer about what God provides by way of spiritual food, but what we provide for ourselves by way of rituals of our own design which are aimed at our own self-esteem rather than at heavenly realities.

That being said, it is a fact that our Lord does not supply all of this miracle himself: he still chooses to require the raw materials from us, just as he used the loaves and fish, meager and insufficient as they were, to feed the multitude. Which surely points to the fact that grace is not completely a gift, but relies on our own efforts to make it work within us. And when we are open to receiving that grace, we can do what we were tempted to think was impossible. We can confront, for example, some moral teaching of the Church and say to ourselves, “Well, I can’t do this; it’s impossible!” almost as impossible as feeding five thousand men with five loaves of bread and two pieces of fish. What makes it possible, of course, is Christ, who said, "With God, all things are possible."

And so it must be with us. There is no burden that the Gospel imposes on us that cannot be met with the grace of Christ. Remembering that at all times, especially in times of temptation, can make all the difference.

We profess our faith at the Holy Mass on Sundays because the Eucharist is not fellowship, it's a sacramental reality; only those who truly believe are allowed to partake of it, because it is real and not just a symbol. And it's important to note that, in the new translation, we no longer say “We believe...,” but “I believe...,” and not simply because that's what the Creed actually says, but because it's at this point that Holy Mass ceases to be a mere communal celebration, but imposes on us an individual decision: I—and no one else—am responsible for seeing that my reception of Holy Communion is worthy. I—and no one else—must confront the Blessed Sacrament of our Lord's Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity, and question the state of my soul to receive it, and whether I should have confessed my sins to a priest first. I—and no one else—must decide if, when I approach for Holy Communion, I really and truly understand what it is I'm presuming to receive, or whether I'm just another lemming in that multitudinous throng that shuffles forward to receive simply because that's what you do at that time in the Mass.

In the final analysis, it's up to each of us as individuals to decide what's in our hearts whenever we are privileged to be present at the miracle that is the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, and whether we can sing, along with King David in our Responsorial Psalm today: “Aperis tu manum tuam, Domine, et satias nos”—“The hand of the Lord feeds us; he answers all our needs.”

|