Don't Lose Your Head Over Things that Don't Matter.

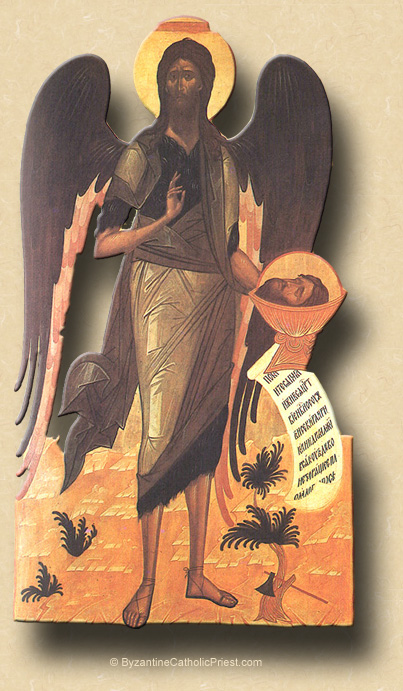

The Memorial of the Passion of Saint John the Baptist.

Lessons from the proper, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Jeremiah 1: 17-19.

• Psalm 71: 1-6, 15, 17.

• Mark 6: 17-29.

|

…or, first and second lessons from the primary feria for the Twenty-First Thursday of Ordinary Time:

• I Thessalonians 3: 7-13.

• Psalm 90: 3-5, 12-14, 17.

…the Gospel above from the proper being required.

|

The Third Class Feast of the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist; and, the Commemoration of Saint Sabina, Martyr.*

Lessons from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Jeremiah 1: 17-19.

• Psalm 91: 13-14.

• Mark 6: 17-29.

|

When a Mass for the commemoration is taken, lessons from the common "Me exspectavérunt…" for a Holy Woman Matyr:

• Ecclesiasticus 51: 13-17.

• Psalm 45: 6, 5.

• Matthew 13: 44-52.

|

FatherVenditti.com

|

10:40 AM 8/30/2019 — In the Ruthenian Catholic Church, in which I served for many years, there are many feasts surrounding the life and death of the Baptist. There’s the Feast of the Nativity of John the Baptist, which we also celebrate; then there’s a feast concomitant with today’s memorial, though observed on a different day; they also have a feast of the First and Second Findings of the Head of the Baptist, so John seems to have lost his head a number of times. 10:40 AM 8/30/2019 — In the Ruthenian Catholic Church, in which I served for many years, there are many feasts surrounding the life and death of the Baptist. There’s the Feast of the Nativity of John the Baptist, which we also celebrate; then there’s a feast concomitant with today’s memorial, though observed on a different day; they also have a feast of the First and Second Findings of the Head of the Baptist, so John seems to have lost his head a number of times.

Mark’s account of how the Forerunner met his death is, oddly enough, told by means of a flash-back. Herod, the Jewish puppet king set up by the Romans, has heard something or our Lord—how His preaching has effected so many people, and how He seems to be working many miracles—and becomes intrigued and a little nervous, wondering if John the Baptist has been somehow resurrected, whereupon Mark recounts for us the history between Herod and the Baptist.

Herod is a complicated individual. He’s kind of like the President of Vichy France: he loves his country, and considers himself a devout Jew, and reasons that what’s best for his country and his religion is to keep the Romans happy; so, he collaborates with them, allowing himself to be set up in this position of pretended authority. In reality, the Romans used him to perpetuate an ongoing land-grab in Palestine; but, from Herod’s perspective, the uncompromising position of the Jewish Zealots, who wanted only to rise up in revolution against Rome and throw them out, wasn’t practical. It's analogous, perhaps, to the Church seeming to embrace secular causes in an attempt to improve its image among those who will continue to attack her regardless, then labeling as extremists those of her own who recognize the futility of betraying tradition and truth for the sake of getting along.

But like our Blessed Lord, John was not political. What turned Herod against John was the Baptist publicly shaming him for having married his brother’s widow. To be fair, the Old Testament is contradictory on the subject, at one point allowing the practice if one’s brother died without issue, then condemning the practice later. But the bottom line is that John condemned his king not for political reasons, but for moral ones, and the story of his death has all the earmarks of a tabloid scandal.

From a spiritual perspective, I think one of the things the story of John’s Passion teaches us is that, in the end, the so called “big issues” of the day don’t matter very much. What’s really important is the state of our souls. When we allow ourselves to get caught up in current events and social, secular and political concerns, we end up distracting ourselves from what really matters. That’s not to say that these other things aren’t important, because they obviously are; but, what we think or do about the environment or immigration or who gets elected to this or that has nothing to do with weather we go to heaven. As I’ve said many times: our one purpose for being on this earth is to work out our salvation; everything else is just window-dressing.

* Sabina, a noble Roman widow, suffered martyrdom under the Emperor Hadrian in AD 126. A Mass for a commemoration falling on a feast of the Third Class would only be taken if it were not the only Mass of the day.

|