True Humility is a Extra Shrimp Cocktail.

The Twenty-Second Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Sirach 3: 17-18, 20, 28-29.

• Psalm 68: 4-7, 10-11.

• Hebrews 12: 18-19, 22-24.

• Luke 14: 1, 7-14.

The Fifteenth Sunday after Pentecost.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Galatians 5: 25-26; 6: 1-10.

• Psalm 91: 2-3.

• Luke 7: 11-16.

The Fifteenth Sunday after Pentecost; the Feast of Our Venerable Father Moses the Ethiopian; the Feast of Our Holy Father Augustine, Bishop of Hippo; the Feast of the Holy Martyr Gebre Michael, Priest of Ethopia; the Remembrance of Our Venerable Mother Laurentia Herasymiv.*

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• II Corinthians 4: 6-15.

• Matthew 22: 35-36.

|

In monastic communities:

The Fifteenth Sunday after Pentecost; and, the Synaxis of the Venerable Fathers of the Pecherskaja Lavra.

Lessons as above.

|

FatherVenditti.com

|

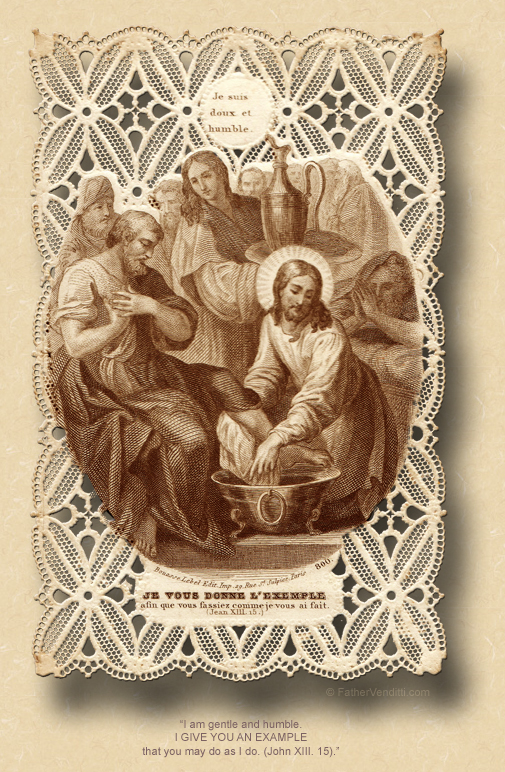

7:29 AM 8/28/2016 — You have to have noticed—unless you’re asleep, which is quite possible whenever I’m preaching—that the Scripture lessons of today’s Mass focus our attention on that one virtue which is the foundation of all others: the virtue of humility. It’s so necessary as the soil for the growth of every other Christian virtue that our Lord takes advantage of every opportunity He can find to explain it to His disciples. In the particular event recorded for us by Saint Luke today, He’s been invited to dinner at the home of one of the leading Pharisees, and He notices how the guests, as they arrive, are all jockeying for a better seat at the table, either closer to Him or to their host. It’s probably after everyone is seated and settled and started to dig into their shrimp cocktails that He tells them a parable. 7:29 AM 8/28/2016 — You have to have noticed—unless you’re asleep, which is quite possible whenever I’m preaching—that the Scripture lessons of today’s Mass focus our attention on that one virtue which is the foundation of all others: the virtue of humility. It’s so necessary as the soil for the growth of every other Christian virtue that our Lord takes advantage of every opportunity He can find to explain it to His disciples. In the particular event recorded for us by Saint Luke today, He’s been invited to dinner at the home of one of the leading Pharisees, and He notices how the guests, as they arrive, are all jockeying for a better seat at the table, either closer to Him or to their host. It’s probably after everyone is seated and settled and started to dig into their shrimp cocktails that He tells them a parable.

The parable He tells them is simple enough and, if we were to take it at face value, would rise no higher than the level of home-spun wisdom about how, in the long run, it’s always better to know your place and not be too ambitious. Centuries later, the spiritual doctors of the Church would identify ambition as a sub-set of the sin of pride, a disordered tendency to look for honor, to exercise authority, to have a position over others, to always think that those who have authority over us are less capable than we are. It’s a temptation in every walk of life, but especially in the Holy Priesthood, and every priest, I think, goes through a period in his life where he thinks his bishop, his dean, or anyone else appointed over him isn’t doing the job nearly as well as he could, and if everyone would just listen to him then life would be grand.

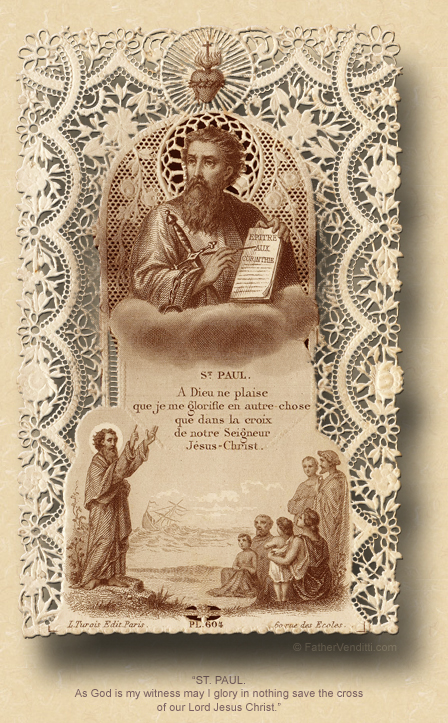

Now, I know that most of you here on a Sunday aren’t here during the week, but the parable our Lord tells in today’s Gospel lesson is really the concluding punchline, if you will, of what the Church has had us reading from the Epistles of Saint Paul all this week; and, those who do assist at Mass here every day will, I’m sure, forgive me if I review it and bring you up to speed.

These lessons from Paul’s letters to the Thessalonians and the Corinthians spawn from his failed preaching tour through Greece and, should you pick up these letters and read them through, you’ll notice that one of the underlying themes to which he returns again and again is how everything we do that is good is actually done by Christ working through us. Yesterday's first lesson, perhaps, contained the most direct statement of this truth: “If anyone boasts, let him make his boast in the Lord” (I Cor. 1: 31 Knox). He's actually quoting there from Jeremiah 9: 23.

He has good reason to hammer away at this point because of his experiences in Corinth, which those who attend daily Mass here have been hearing about. The Apostle had been talking about the paradox of the Cross, and he drew a rather insightful comparison between what he called “the wisdom of this world” (I Cor. 1: 20) and the simplicity of the Christian's faith in the Cross.  When Saint Paul arrives in Corinth it's the largest commercial center in the world, and everybody from all over the world is there; its intellectual life, such as it was, was centered on the emerging musings of the Greek philosophers. Paul had failed to convert the Greek philosophers during his stay in Athens prior to arriving in Corinth; so, perhaps here he finds an opportunity to twist the knife a little with the devotees of Socrates. Paul's converts in Corinth came from every walk of life, but most of them from the lower classes; they wouldn't have been welcomed at the cocktail parties of the intellectual elite debating Xenophon and Plato over their cucumber sandwiches; nor would they want to be, as Paul reminds them to simply open their eyes and see how unhappy and unfulfilled all these “beautiful people” are. In Friday’s Epistle he asks them, “What has become of the wise men, the scribes, the philosophers of this age we live in? Must we not say that God has turned our worldly wisdom to folly?” (v. 20 Knox). When Saint Paul arrives in Corinth it's the largest commercial center in the world, and everybody from all over the world is there; its intellectual life, such as it was, was centered on the emerging musings of the Greek philosophers. Paul had failed to convert the Greek philosophers during his stay in Athens prior to arriving in Corinth; so, perhaps here he finds an opportunity to twist the knife a little with the devotees of Socrates. Paul's converts in Corinth came from every walk of life, but most of them from the lower classes; they wouldn't have been welcomed at the cocktail parties of the intellectual elite debating Xenophon and Plato over their cucumber sandwiches; nor would they want to be, as Paul reminds them to simply open their eyes and see how unhappy and unfulfilled all these “beautiful people” are. In Friday’s Epistle he asks them, “What has become of the wise men, the scribes, the philosophers of this age we live in? Must we not say that God has turned our worldly wisdom to folly?” (v. 20 Knox).

Now, understand that when we set out to decipher—and that's the right word—what Paul is saying in these letters, we're taking a gamble. Paul would visit these places, establish the Church there, then move on; and, as he was traveling along to the next mission, he would stop at various places and check his messages, kind of like how people would sometimes stop at an Internet cafe to check their e-mail in the days before smart phones;—if anyone remembers what an Internet cafe is—and, if he got a message that there was some problem back in one of these places that needed correction, he would fire back a letter to that effect. The problem for us is that we only have one side of the correspondence; the Apostle is answering questions and handing down decisions, but we can only surmise from his words what question was asked or what dispute needed to be decided.

My guess is—and it would only be a guess—that some of his converts in Corinth were suffering from an inferiority complex, kind of like what we go through when we watch too many episodes of “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.” Perhaps some of the Corinthian Christians thought they could “mainstream” themselves by going to those cocktail parties and arguing Christianity as a competing philosophy. Kind of like what happens when Church leaders in our own day try to make themselves relevant by speaking out on all sorts of secular matters, like immigration reform or race relations or global warming or anything that happens to be in the news at the moment, in an attempt to prove to the editors of The New York Times that the Catholic Church is relevant, too. Paul tried it himself when he was in Athens, when he attempted to preach in the Temple of the Unknown God (cf. Acts 16: 16—18: 1), and it didn't work; they laughed him out of town. And he doesn't want to see the Corinthians make the same mistake, so he reminds them where they come from, to actually relish the fact that they come from the wrong side of town, to realize that the truth they posses does not come from themselves but from Christ:

Consider, brethren, the circumstances of your own calling; not many of you are wise, in the world’s fashion, not many powerful, not many well born. No, God has chosen what the world holds foolish, so as to abash the wise, God has chosen what the world holds weak, so as to abash the strong (1: 26-27 Knox).

In other words, you don't want to be like them. What makes you “wise”—if that's the word you want to use—is Christ; which leads up to his punchline: “Whoever boasts, should boast in the Lord” (v. 31 NAB).

In the Ruthenian Catholic Church in which I used to serve, whenever one had the occasion to offer the Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil the Great, there is a part of the Eucharistic Prayer in which the priest prays to God saying, “We have done nothing good upon the earth,” and it’s true.  Everything good in this world comes from God, and everything we might do that’s good is done by God working through us by means of Grace. It harkens back to something said by Cardinal Ratzinger just a few months before he become pope: that the goal of the Christian life is to “get out of God’s way,” to submerge ourselves so that we become Christ living and acting through us, as John the Baptist said: “He must increase; I must decrease” (John 3: 20 NABRE). Everything good in this world comes from God, and everything we might do that’s good is done by God working through us by means of Grace. It harkens back to something said by Cardinal Ratzinger just a few months before he become pope: that the goal of the Christian life is to “get out of God’s way,” to submerge ourselves so that we become Christ living and acting through us, as John the Baptist said: “He must increase; I must decrease” (John 3: 20 NABRE).

So, the true nature of the virtue of humility has nothing to do with being shy or timid or mediocre; quite the contrary. True humility should cause us to recognize that whatever talents and abilities we have are given to us by God to be used in His service, and our possession of them should cause in us a profound sense of gratitude. True humility doesn’t consist of staying passive and in the background, and those who interpret it that way usually end up accomplishing nothing for God. At the same time, true humility always prompts us to self-examination, which is why true humility only becomes authentic when it is tempered and nourished frequently in the confessional.

In his Introduction to the Devout Life, Saint Francis de Sales provides us with a striking image: he describes us all as mules, and goes on to say that the mule is a disgusting beast. And then he says, “Alas! Do mules cease to be disgusting beasts simply because they are laden with the precious and perfumed goods of the prince?” (Introduction to the Devout Life, III, 5). The parallel he makes between man’s life and beasts of burden is very valid, and echos the words of the Psalmist:

I was all dumbness, I was all ignorance, standing there like a brute beast in thy presence. Yet ever thou art at my side, ever holdest me by my right hand. Thine to guide me with thy counsel, thine to welcome me into glory at last. What else does heaven hold for me, but thyself? What charm for me has earth, here at thy side? What though flesh of mine, heart of mine, should waste away? Still God will be my heart’s stronghold, eternally my inheritance (Psalm 73: 22-26 Knox).**

And there you have the paradox and the challenge of practicing the virtue of humility: God has given each of us talents and abilities to do many great things. We have no right to submerge them, since God has given them to us for a purpose. The danger is that when, as God’s mules, we are given a sack of precious jewels and treasures to carry behind the prince, we make the mistake of thinking that the treasure is ours and that we earned it somehow, when our job is nothing more than to deliver the cargo where directed. Think back to our Lord at the Pharisee’s dinner party, watching his fellow guests jockey for the best seats at table. Do we think that, because we’ve got a seat closer to the host, we’re going to get a better shrimp cocktail? Personally, I like to sit far away from the center of the action, because there’s always someone else just as unimportant as me who was supposed to sit there and didn’t show up, then I can eat their shrimp cocktail.

The bottom line is that the humble soul is constantly on the watch for the Will of God, whereas the proud soul has eyes only for its own way, its own preferences, its own ambition, its own achievements and aims, thus closing the door to God’s Grace. It doesn’t realize it because everything it sees is through its own backward-looking gaze, always concerned for how it appears. Like Saint Paul says,

God chose the lowly and despised of the world, those who count for nothing, to reduce to nothing those who are something, so that no human being might boast before God … so that, as it is written, “Whoever boasts, should boast in the Lord” (I Cor. 1: 28-29, 31 NABRE).

* Moses the Ethiopian, also called the Abyssinian, led a riotous life before his conversion in the fourth century, retiring to a solitary life in the deserts of Egypt.

Gebre Michael, a priest of the Ethiopian Church, often called the Englightener of Ethiopia, died for the faith in 1855.

The typicon of the Ruthenian Church contains serveral "remembrances" of the passing of certain individuals who are not yet beatified nor canonized, and Sr. Laurentia is one of these. Born in Ukraine, she joined the Sisters of Saint Joseph in 1933, and was arrested for her faith by the NKVD in 1951. She was sent to Borislav in the modern Czech Republic, then exiled to Tomsk, Siberia, where she contracted tuberculosis, and was relocated to Kharsk, Siberia, on June 30th, 1952, where she died.

Since these remembrances are provided with no chants or texts, it has always been unclear exactly how they should figure in the liturgy or office of the day. The typicon itself offers no instruction as to what to do with them, which begs the question why they are included on the calendar. It can't be for purposes of personal devotion since the typicon is not a devotional work, and offers no information about the individual mentioned other than the name. Because these remembrances appear on the calendar, I include the reference to them when indicated.

** In translations based on the Hebrew Psalter, this would be Psalm 72. Msgr. Knox’s translation is based on the Greek.

|