The Divine Liturgy, Part Eleven: The Salad Bar is Closed.1 Cor. 15:1-11; Matt. 28:16-20. The Twelfth Sunday after Pentecost, known as The Twelfth Sunday of Matthew. Also, the Holy Martyr Babylas, Bishop of Antioch, and the Holy Prophet Moses who Saw God.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

12:31 PM 9/4/2011 — One of the most familiar parts of the Divine Liturgy is the Creed. We touched on the subject briefly in the beginning of the summer by way of example. In talking about our old friend, St. Germanus of Constantinople, who wrote that magnificent treatise on the Liturgy which has proved so important over the years, we used his remarks about the Creed to illustrate how there are some things done in the Liturgy which we will never understand.  St. Germanus remarks about the priest waving the veil over the gifts during the singing of the Creed, and tells us that, while there are many different theories about what it means, the truth is we don’t really know for sure what it’s all about.* St. Germanus remarks about the priest waving the veil over the gifts during the singing of the Creed, and tells us that, while there are many different theories about what it means, the truth is we don’t really know for sure what it’s all about.*

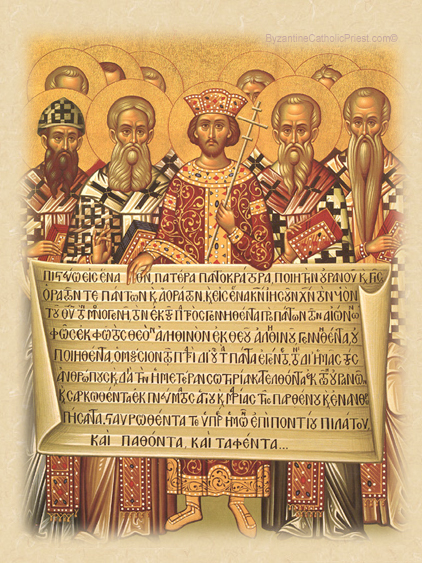

The Creed itself, however, we do know something about. The word “creed” comes from the first word of the text in Latin, credo, which means “I believe.” And that’s essentially what a creed is: it’s a statement of what we believe. We could spend an entire afternoon discussing creeds and their origins and meanings; but to sum it all up much too quickly, the Church composes creeds in order to define it’s faith in a time of crisis. The Apostles Creed, for example, defines those articles of faith the apostles thought needed explanation and defense at the time; the Nicean Creed, which we sing in church, was composed at the Council of Nicea to give a definitive answer to the heresies of Arius and the Gnostics and the Nestorians—whom we’ve talked about before—which is why it places so much emphasis on Jesus being of one substance with the Father. There are dozens of creeds composed by the Church over the centuries. The shortest creed, composed in the second century, is a single sentence stating simply that Jesus is God. The longest creed was composed by our late Holy Father Pope Paul VI, and is several pages long—aren’t you glad we don’t have to sing that one on Sunday?** We sing the Creed of Nicea on Sunday only because it has that combination of both important content and relative brevity which makes its use in the Liturgy easy. It states most of the important dogmas of Christianity, particularly about the nature of Christ Himself; and, yet, it’s short enough that it doesn’t take until Thursday to sing it. And when you look at the heresies that the Council of Nicea was dealing with—some of which, as I said, we’ve discussed—it’s also the creed which can be said to have had the most profound impact on the life of the Church. It’s interesting to note that, in the Latin Church, the Nicean Creed is the one most often used at Mass, but the priest has the option of using the Apostles Creed as well, particularly in Masses celebrated with children, since memorizing the Apostles Creed is usually part of their catechism.

But what I would like to offer for your reflection today is not anything about the content of the Creed or which creed is the best one to use in the Liturgy; but rather the question of where the creed is placed in the context of the service; because, as we shall see, in almost every form of Eucharistic Liturgy, whether Roman or Syrian or Coptic or whatever, the creed is sung or recited at about the same time during the Liturgy. But in the Constantinopolitan or Byzantine Liturgy it’s in a different place, and it’s place is important.

Two weeks ago, you’ll remember, we spoke about the Dismissal of the Catechumens after the first part of the Liturgy; because in the early Church, only full fledged members of the Church were allowed to participate in the Eucharist. And we mentioned how the whole Liturgy is, thus, divided into two parts: the Liturgy of the Catechumens, consisting of the opening litany, the antiphons, the readings, the homily; and the Liturgy of the Faithful, consisting of the Consecration and Holy Communion. In almost every Eucharistic Liturgy in Christianity, the Creed takes place during this first part of the Liturgy. Those who have been to Roman Catholic Mass will recall that after the priest is done giving his speech, he’ll say something like, “Let us now make our profession of faith,” and everyone stands up and recites the Creed. It’s the same in almost every rite you can find, except one: in the Byzantine Rite, the Creed is sung not in the first part of the Liturgy, but in the second, just before the Consecration. It is not a minor point; and it is a very good illustration of how the Byzantine Liturgy is so much closer to the actual practice of the Apostles and the early Church than most other Liturgies used today.

The explanation is very similar to what we discussed two weeks ago concerning the catechumens. In the early Church, there was a great deal of concern about one having to be a real member of the Church in order to participate in the Eucharist. That’s why the catechumens, who were not yet baptized, had to get up and leave after the sermon. The Churches of the East coming out of Constantinople—in other words, the Byzantine Churches—believed, as we do today, that to be a member of the Church it wasn’t enough to just show up, you had to believe what it was the Church taught and believed. You could not reject the teaching of the Church and still call yourself a member.  That would be hypocrisy. So, from the earliest recorded Liturgies on, the singing or reciting of the Creed was directly linked to the Eucharist itself, taking place not after the sermon, but as an actual part of the prayer that makes the Consecration. In other words, the prerequisite for witnessing the miracle of bread and wine becoming the flesh and blood of Christ was that you first had to stand up and say, “I believe in this, this, this and this.” Because if you don’t believe this, then you have no business being here and are not entitled to see what we’re about to do here. It is perhaps the most striking example of how the Byzantine Liturgy differs from all other liturgies in the Church: that the Creed is linked to the Eucharist. It is the Eucharist that makes us members of the one Body of Christ; and you cannot be a member of the one Body of Christ if you don’t believe. That would be hypocrisy. So, from the earliest recorded Liturgies on, the singing or reciting of the Creed was directly linked to the Eucharist itself, taking place not after the sermon, but as an actual part of the prayer that makes the Consecration. In other words, the prerequisite for witnessing the miracle of bread and wine becoming the flesh and blood of Christ was that you first had to stand up and say, “I believe in this, this, this and this.” Because if you don’t believe this, then you have no business being here and are not entitled to see what we’re about to do here. It is perhaps the most striking example of how the Byzantine Liturgy differs from all other liturgies in the Church: that the Creed is linked to the Eucharist. It is the Eucharist that makes us members of the one Body of Christ; and you cannot be a member of the one Body of Christ if you don’t believe.

In today’s world, this concept is a lot more important than you might think. We live today during a time in which the most prevalent moral philosophy is one of relativism: what’s good for you may not be good for me; what’s right for you is not necessarily right for me; what’s immoral for me is perfectly OK for you; what’s true for me doesn’t have to be true for you. Good and bad, right and wrong, moral and immoral, true and false are all based on how someone feels about it. Every time someone brings up a topic like abortion or gay marriage or any of today’s hot-button issues, what do you hear? “How can you impose your personal beliefs upon someone else?” Even among Catholics you sometimes hear this, almost as if the teachings of our Lord and His Church are being presented in the form of some sort of theological salad bar, where we just pick out what we like and leave what we don’t. The early Christians were smart: they knew this was a problem during the persecutions, and they knew it was going to continue to be a problem even after the persecutions were over. They knew that Christians would always be tempted to follow the path of least resistance and bend on moral issues and issues of faith. And that’s why, in the earliest Liturgies of the Church, particularly those of Byzantium, they put the Creed right into the prayer of Consecration, so that no one would be able to approach for Holy Communion without first standing up and saying, “I believe in One God, the Father almighty, creator of heaven and earth, and in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten of the Father, and I believe in this and I believe in that...” Because if you don’t believe what we believe, then you’re not one of us, and you’re not going to receive anything.

You might remember, after Pope John Paul’s funeral, Cardinal Ratzinger concelebrated a Mass in St. Peter’s with all the Cardinals the day before they went into the conclave. And he preached this hell-fire and brimstone German-Lutheran sermon about Christian culture and how all of Europe was going to hell in a handbag. And he said that he would much prefer to see a small Church of committed faithful believers than a large Church full of people whose faith was marginal. And all sorts of bishops and priests and magazine editors in this country got all excited and upset about this old codger from medieval Bavaria and his twisted vision of the future. And everyone was saying how he doesn’t understand us; and, here, we’re about meeting people where they’re at and accommodating everyone we can, blah blah blah. Well, the old codger is now pope, and his vision isn’t twisted, it’s crystal clear. It is, in fact, the vision of the early Church. And you may have noticed, those of you who are old enough to remember other papal installations from John Paul II, John Paul I, Paul VI, John XXIII—some may even remember the coronation of Pius XII just before World War II—at the installation of Pope Benedict the XVI, the patriarchs and Metropolitans of the Eastern Catholic Churches had a much bigger role than they’ve ever had. It was the heads of the Eastern Churches that escorted the new pope to the Confessio under the altar of St. Peter’s, to take from the tomb of the Apostle the pallium that signifies the office of the Vicar of Christ. These things were not by accident. Nor is it an accident that this man is an expert on the writings of St. Augustine. Pope Benedict’s vision for the future of the Church is the faith and fervor of the early Christians—that same faith and fervor that is expressed so beautifully in the Divine Liturgy of the Byzantine Rite.

So, as we sing the words of the Creed today, let’s remember that what we are singing is far more important than just the meaning of the words. It is a symbol of an undying faith, a faith that could not be destroyed by 300 years of persecution, and that won’t be trivialized by a thousand years of indifference and pressure to conform.

Father Michael Venditti

* Cf. the homily for The First Sunday after Pentecost, 6/19/2011.

** Motu Proprio Solemni hac Liturgia (Credo of the People of God), June 30, 1968.

|