Don't Make the Mistake of Rejecting the Truth Because the Church Is Led by Sinful People.

The Twenty-First Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the secondary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Joshua 24: 1-2, 15-17, 18.

• Psalm 34: 2-3, 16-21.

• Ephesians 5: 21-32.

[or, 5: 2, 25-32.]

• John 6: 60-69.

The Fourteenth Sunday after Pentecost.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Galatians 5: 16-24.

• Psalm 117: 8-9.

• Matthew 6: 24-33.

FatherVenditti.com

|

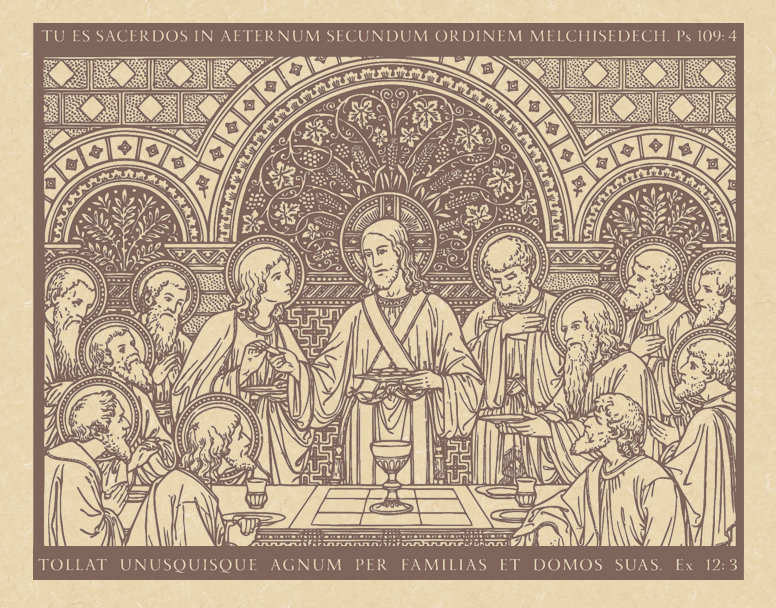

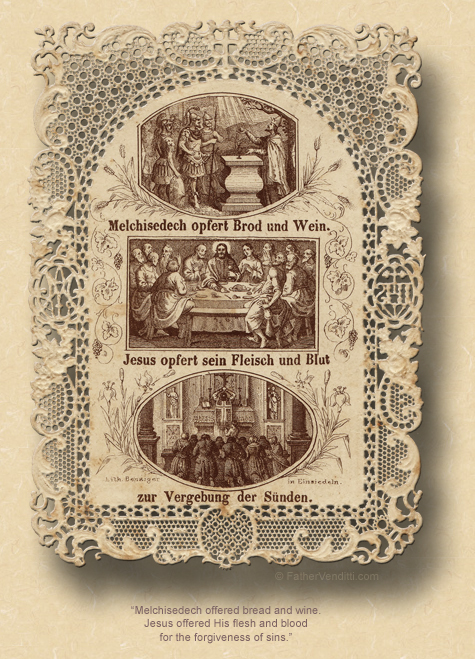

11:17 AM 8/26/2018 — Yesterday I had reflected with those who were here for Holy Mass on our Lord’s admonition to his followers to obey everything taught to them by the Scribes and Pharisees, just not to follow their example; and, we had made the analogy to what we are suffering as a Church right now, recognizing that even if a bishop is a criminal, that doesn’t mean the doctrine he has taught in the name of Christ isn’t true, nor that we are not bound by it, just as the relative holiness or sinfulness of a priest doesn’t cancel the fact that the Eucharist he consecrates at Holy Mass is still the real Body and Blood of our Lord. The Blessed Eucharist has been the theme of the Sunday Gospels for a number of weeks now; and, as difficult as it may seem, we must not forget that the reality of the Eucharist doesn’t depend on the holiness or conduct of the priest, but simply on the fact that he is a priest. 11:17 AM 8/26/2018 — Yesterday I had reflected with those who were here for Holy Mass on our Lord’s admonition to his followers to obey everything taught to them by the Scribes and Pharisees, just not to follow their example; and, we had made the analogy to what we are suffering as a Church right now, recognizing that even if a bishop is a criminal, that doesn’t mean the doctrine he has taught in the name of Christ isn’t true, nor that we are not bound by it, just as the relative holiness or sinfulness of a priest doesn’t cancel the fact that the Eucharist he consecrates at Holy Mass is still the real Body and Blood of our Lord. The Blessed Eucharist has been the theme of the Sunday Gospels for a number of weeks now; and, as difficult as it may seem, we must not forget that the reality of the Eucharist doesn’t depend on the holiness or conduct of the priest, but simply on the fact that he is a priest.

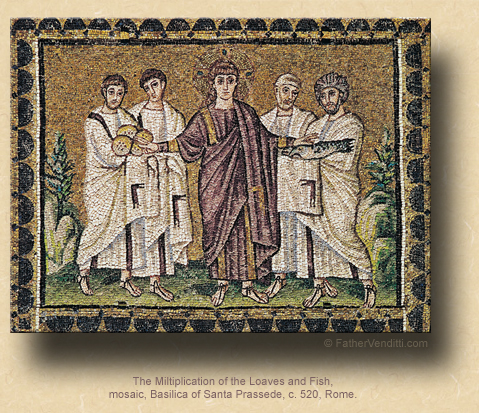

Last week we had heard a Gospel lesson which was part of the fallout from the miracle of the loaves, wherein our Lord makes His most profound statement about the Blessed Eucharist: Ego sum panis vitæ: qui venit ad me, non esuriet, et qui credit in me, non sitiet umquam—“I myself am the living bread that has come down from heaven. If anyone eats of this bread, he shall live for ever. And now, what is this bread which I am to give? It is my flesh, given for the life of the world (John 6: 51-52 Knox). And, of course, we know that our Lord does not speak figuratively. Today’s Gospel lesson is the fallout from that statement made in last week’s, which caused some of our Lord disciples to desert Him: “This saying is hard [Saint John quotes them as complaining]; who can accept it?” (v. 61 NABRE).

The miracle of the previous day had awakened the crowd's deepest hopes and longings. Thousands of people had left the comfort of their homes to come and hear our Lord. Saint John goes so far as to tell us that the people were so moved by the day's events that they wanted to carry our Lord off and make Him king; —that's why he secreted Himself away when they weren't looking—but, when they caught up with Him, He turned the tables on them and accused them of being somewhat mercenary: “Believe me [He says in verse 26], if you are looking for me now, it is not because of the miracles you have seen; it is because you were fed with the loaves, and had your fill” (6: 26); in other words, He's accusing them of seeking Him, not because the miracle has convinced them of His divinity, but because they got a free meal out of it, and were probably looking for breakfast. Saint Augustine commented on this, paraphrasing our Lord and making an observation: “You seek me for worldly motives, not for spiritual ones. How many people are there who seek Jesus solely for worldly ends! … Rarely does someone look for Jesus for the sake of Jesus” (Commentary on John, 25, 10). —that's why he secreted Himself away when they weren't looking—but, when they caught up with Him, He turned the tables on them and accused them of being somewhat mercenary: “Believe me [He says in verse 26], if you are looking for me now, it is not because of the miracles you have seen; it is because you were fed with the loaves, and had your fill” (6: 26); in other words, He's accusing them of seeking Him, not because the miracle has convinced them of His divinity, but because they got a free meal out of it, and were probably looking for breakfast. Saint Augustine commented on this, paraphrasing our Lord and making an observation: “You seek me for worldly motives, not for spiritual ones. How many people are there who seek Jesus solely for worldly ends! … Rarely does someone look for Jesus for the sake of Jesus” (Commentary on John, 25, 10).

But there is a sense, if you will forgive me, in which we can take issue with this great Father of the early Church; because, for those of us who are faithful Catholics, we know that there's nothing that draws more people to love and devotion than the worship of the Most Blessed Sacrament. Why is that, beyond, of course, the obvious fact the Eucharist is our Lord? I think that Pope Saint John Paul II might have hit on it in one of his homilies. He said,

It is only by means of the Eucharist that we are able to live the heroic virtues of Christianity, such as charity to pardon one's enemies, the love which enables us to suffer, the capacity to give one's life for another; chastity at all times of life and in all situations; patience in the face of suffering and the apparent silence of God in human history or our very own existence. Therefore, strive to always be Eucharistic souls so as to be authentic Christians (Homily, Aug. 19, 1979).

Now, that's a mouthful, and if we were to parse that paragraph there's a lot we could reflect on there; but, suffice it to say that living the Christian life in this difficult age, when just being a believer makes one suspect and outcast, and in which temptations are thrown at us from every side almost as if society itself has invested itself in our own personal fall from grace, the faithful Catholic knows that it's the Body and Blood of the Lord that enables him to remain faithful, and it's the Body and Blood of the Lord that gives him the courage to pick himself up and try again when he fails.

When the crowd heard our Blessed Lord describe the Eucharist, albeit in symbolic terms, they pleaded with him, Domine, semper da nobis panem hunc—“Lord, give us this bread always” (6: 34); and, while they may not have understood exactly what they were asking, we do. Our Lord leaves no room for doubt that this “bread,” as He calls it, is real. He repeats the verb βεβρωσχω—“to eat”—eight times! Christ becomes food so we might gain a new life: “…what is this bread which I am to give? It is my flesh, given for the life of the world.” That's our Lord commenting on the Manna in the desert from Exodus. The Manna was a symbol; the Eucharist is not.

When we receive Communion, we receive Christ Himself, with His Body, His Blood, His Soul and Divinity. Our life is transformed into His life. In Holy Communion, Christ is not only God with us, but God in us. Saint Augustine, who always finds unique ways of looking at things, gets very graphic and describes the reception of Holy Communion in terms of the physiology of eating and digesting. He points out that, when we eat normal food, we digest it and it becomes part of us; but, when we receive our Lord in Holy Communion, He does not become a part of us, we become a part of Him; assuming we are in the state of grace and can receive Him worthily, we actually become what we have consumed (cf. Confessions, 7, 10, 16; 7, 18, 24). Christ gives us his life. He “divinizes” us. He transforms us into Himself. The infinite merits of His Passion are poured into our soul. He sends His strength and consolation.  He leads us to His Most Sacred Heart, to transform our hopes and dreams into His. That's because the Blessed Sacrament, as the Second Vatican Council says, “contains all the spiritual good of the Church” (Presbyterorum ordinis, 5). Thus, our goal should be, whenever we receive Holy Communion, to be able to say along with Saint Paul, “…it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me” (Gal. 2: 20 RSV). Of course, once we know this, we know that it must effect how we live our lives, and that the words of our Lord at the Last Supper must be fulfilled in us at every Holy Communion: “If a man loves me, he will keep my word, and my Father will love him, and we will come to him and make our home with him” (John 14: 23 RSV). He leads us to His Most Sacred Heart, to transform our hopes and dreams into His. That's because the Blessed Sacrament, as the Second Vatican Council says, “contains all the spiritual good of the Church” (Presbyterorum ordinis, 5). Thus, our goal should be, whenever we receive Holy Communion, to be able to say along with Saint Paul, “…it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me” (Gal. 2: 20 RSV). Of course, once we know this, we know that it must effect how we live our lives, and that the words of our Lord at the Last Supper must be fulfilled in us at every Holy Communion: “If a man loves me, he will keep my word, and my Father will love him, and we will come to him and make our home with him” (John 14: 23 RSV).

The end of our Gospel lesson today, which is also the end of chapter six of John’s Gospel, is a sobering but very timely exchange between our Lord and His Apostles. It’s timely because of so many who have left or will leave the Church because of those who have given scandal, not thinking that they are depriving themselves of the Eucharist. After our Lord tells his disciples that His flesh is real food and His blood is real drink … I’ll give you Msgr. Knox’s translation, only because it's my favorite:*

After this, many of his disciples went back to their old ways, and walked no more in his company. Whereupon Jesus said to the twelve, Would you, too, go away? Simon Peter answered him, Lord, to whom should we go? Thy words are the words of eternal life; we have learned to believe, and are assured that thou art the Christ, the Son of God (John 6: 67-70 Knox).

* Ronald A. Knox was born in 1888, the son of the Anglican Bishop of Manchester, and was a brilliant scholar from the start. At the tender age of twenty-four he became the Anglican chaplain of Oxford's Trinity College, but resigned in 1917 to enter the Catholic Church, and was quickly ordained to the Holy Priesthood. He returned to Oxford as a Catholic chaplain, but had to fend for himself, and supported himself by writing detective stories. In 1939 he was commissioned by the Catholic bishops of England and Wales to provide a new translation of the Bible into English to replace the antiquated Douay-Rheims Bible, which was completed in France in 1609 by expatriate English Catholics who had fled their country because of religious persecution; but, because the Douay-Rheims had become so ingrained in the minds of English speaking Catholics around the world for hundreds of years, there was a lot of resistance to the idea of a new translation, and Knox was forced out of Oxford and went into seclusion at the estate of two prominent Catholic converts, Lord and Lady Aston, where he finally completed the translation in 1948. The bishops of England and Wales were so pleased with it that they authorized its use in the Churches of Great Britain. For a brief time, his translation was allowed to be used at Mass in the United States; in England and Wales it is still allowed. * Ronald A. Knox was born in 1888, the son of the Anglican Bishop of Manchester, and was a brilliant scholar from the start. At the tender age of twenty-four he became the Anglican chaplain of Oxford's Trinity College, but resigned in 1917 to enter the Catholic Church, and was quickly ordained to the Holy Priesthood. He returned to Oxford as a Catholic chaplain, but had to fend for himself, and supported himself by writing detective stories. In 1939 he was commissioned by the Catholic bishops of England and Wales to provide a new translation of the Bible into English to replace the antiquated Douay-Rheims Bible, which was completed in France in 1609 by expatriate English Catholics who had fled their country because of religious persecution; but, because the Douay-Rheims had become so ingrained in the minds of English speaking Catholics around the world for hundreds of years, there was a lot of resistance to the idea of a new translation, and Knox was forced out of Oxford and went into seclusion at the estate of two prominent Catholic converts, Lord and Lady Aston, where he finally completed the translation in 1948. The bishops of England and Wales were so pleased with it that they authorized its use in the Churches of Great Britain. For a brief time, his translation was allowed to be used at Mass in the United States; in England and Wales it is still allowed.

The Knox Bible has a lot of critics today, most of whom mistakenly claiming that he simply translated the Latin Vulgate, which isn’t true; he worked directly from the Greek and Hebrew originals, and no one knew Greek and Hebrew better than Knox. He made sense of passages from the Scriptures that even Saint Jerome had trouble with. Unfortunately, the bishops of the United States completed their own, vastly inferior, revision of the Douay-Rheims Bible around the same time, and Knox's Bible never took hold in this country, and was out of print for a long time. Happily, it’s available again. As a Catholic priest he wrote a number of very important books about Protestantism and Catholicism, about language and the art of translation, a number of works of literary criticism, and was the first person after Arthur Conan Doyle to write his own Sherlock Holmes mystery. He died the year I was born. I consider myself to be his spiritual and intellectual child.

|