The Most Famous Words Saint Francis Never Spoke.

The Ninteenth Wednesday of Ordinary Time; or, the Memorial of Saint Stephen of Hungary.*

Lessons from the primary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Deuteronomy 34: 1-12.

• Psalm 66: 1-3, 5, 8, 16-17.

• Matthew 18: 15-20.

|

When a Mass for the Memorial is taken, lessons from the feria as above, or from the proper:

• Deuteronomy 6: 3-9.

• Psalm 112: 1-9.

• Matthew 25: 14-30.

…or, any lessons from the common of Holy Men & Women for One Saint.

|

The Second Class Feast of Saint Joachim, Confessor & Father of the Blessed Virgin Mary.**

Lessons from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ecclesiasticus 31: 8-11.

• Psalm 111: 9, 2.

• Matthew 1: 1-16.

The Tenth Wednesday after Pentecost; a Postfestive Day of the Dormition; the Feast of the Translation of the Icon Not Made by Human Hands; and, the Feast of the Holy Martyr Diomedes.***

First & third lessons from the menaion for the Translation, second & fourth from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Colosians 1: 12-18.

• II Corinthians 3: 4-11

• Luke 9: 51-56; 10: 22-24.

• Matthew 23: 29-39.

FatherVenditti.com

|

9:20 AM 8/16/2017 — Most of you know I was a pastor for many years, and one can’t be a pastor for any length of time without more than one occasion when someone will write to the bishop with some sort of complaint. Often these letters are anonymous, in which case there’s nothing the bishop can do other than forward it to the priest for his information, or just toss it in the waste basket. But if the letter has been signed, and contact information given, if the bishop is a priest of any pastoral experience at all, the first thing he will do is write back to the author of the letter and ask, “Have you spoken to Father about this matter?” Nine times out of ten, the author has not. 9:20 AM 8/16/2017 — Most of you know I was a pastor for many years, and one can’t be a pastor for any length of time without more than one occasion when someone will write to the bishop with some sort of complaint. Often these letters are anonymous, in which case there’s nothing the bishop can do other than forward it to the priest for his information, or just toss it in the waste basket. But if the letter has been signed, and contact information given, if the bishop is a priest of any pastoral experience at all, the first thing he will do is write back to the author of the letter and ask, “Have you spoken to Father about this matter?” Nine times out of ten, the author has not.

Nobody likes confrontation. Some of us will go to extreme lengths to avoid it. One of the questions I get frequently comes from faithful souls who have loved ones who are not practicing their faith, and they want to know whether they should say anything. Their examination of conscience tells them that they should, but they are reticent at the prospect of creating a scene and suffering all the unpleasantness that comes with any confrontation of this sort. This usually happens a lot during holiday seasons when there is the ominous threat of some sort of family gathering on the horizon, and the wayward cousin who’s living in sin has been invited with his or her partner in crime. And I like to advise them to take a step back and ask, “If you were to say such-and-such to this person, what do you realistically believe would be the result?” Not, “What do you want to happen?” or, “What do you hope will happen?” but, “What do you think will actually happen?” Do you really believe that, having heard you out, that person will have a change of heart and return to the life of grace? or, is it more likely that he or she will become even more entrenched and resistant to any attempt to correct his faults?

Our Lord’s discourse to His disciples in today’s Gospel lesson is more about structure and authority in the Church, but it touches on this topic within that context. “If your brother sins against you, go and tell him his fault between you and him alone” (Matt. 18: 15 RM3). The reasons we don’t do that are many and varied;—we’re afraid of confrontation, we’re afraid of being wrong, we’re afraid of having our own faults exposed in some heated argument—but, whatever the reason, we’re always more inclined to complain to our friends, stew about it privately in ourselves, or even write anonymous letters, but the first thing we aught to do—according to our Lord—always turns out to be the last thing in the world we would do.

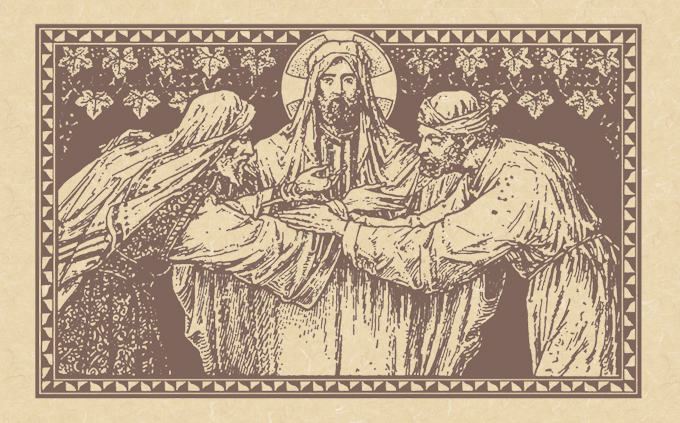

Now, our Lord goes on to outline what steps should be taken should our initial confrontation bare no fruit, and they have more to do with discipline within the Church than anything else, but we can also see the first verse of this lesson as a very profound instruction on the practice of the virtue of fraternal charity.  No matter how offended we may have become at the conduct of another, we are never exempt from the rule of charity. A few of you who are regulars might just remember that line from the Rule of Saint Bruno I quote every year at the beginning of Lent: “Whenever you see a brother doing something forbidden by the rule, always assume he has permission.” We have enough to do policing our own souls, let alone setting ourselves up as arbiters of the souls of everyone else. Besides, when we have our own spiritual and moral houses in order, the example of how we live our faith speaks more eloquently than any words we could speak; or, as some mistakenly believe Saint Francis once said, “Preach the Gospel at all times. Use words if necessary.” Of course, the good Saint Francis never said any such thing, and taken by itself the saying is quite troublesome because it sets up a dichotomy between speech and action. Besides, the spirit behind it can be a little arrogant, intimating that those who “practice the Gospel” are more faithful to the faith than those who preach it, which isn’t true at all. What the Rule of Saint Francis actually says is, “No brother should preach contrary to the form and regulations of the holy Church…. All the Friars … should preach by their deeds.” And that’s quite different from setting up some artificial contest between those who “preach” and those who “do.” No matter how offended we may have become at the conduct of another, we are never exempt from the rule of charity. A few of you who are regulars might just remember that line from the Rule of Saint Bruno I quote every year at the beginning of Lent: “Whenever you see a brother doing something forbidden by the rule, always assume he has permission.” We have enough to do policing our own souls, let alone setting ourselves up as arbiters of the souls of everyone else. Besides, when we have our own spiritual and moral houses in order, the example of how we live our faith speaks more eloquently than any words we could speak; or, as some mistakenly believe Saint Francis once said, “Preach the Gospel at all times. Use words if necessary.” Of course, the good Saint Francis never said any such thing, and taken by itself the saying is quite troublesome because it sets up a dichotomy between speech and action. Besides, the spirit behind it can be a little arrogant, intimating that those who “practice the Gospel” are more faithful to the faith than those who preach it, which isn’t true at all. What the Rule of Saint Francis actually says is, “No brother should preach contrary to the form and regulations of the holy Church…. All the Friars … should preach by their deeds.” And that’s quite different from setting up some artificial contest between those who “preach” and those who “do.”

But sufficient for our purpose today is to simply recognize that it’s the cultivation of prudence and the rule of charity that should guide all those instances in which we bump into other souls as we journey along to our final goal, which is salvation. Because, in spite of the many times we bump into each other along the way, we’re all traveling in the same direction and toward the same goal. Or, as we’ve said so many times this summer, “Our one purpose for being on this earth is to work out our salvation. Everything else is just window-dressing.”

* As the first Christian king of Humgary, Stephen united and Christianized the Magyar people, for which he received the "holy crown" from Pope Sylvester II in the year 1000. Known as the Apostle of Hungary and renowned for his charity to beggers, he died in 1038.

** The holy Patriarch Joachim was the husband of St. Anne and the father of our Lady. This feast, originally kept on March 20th, was tranferred to the day after the Assumption in order to associate the Blessed Daughter and her holy father in triumph. ** The holy Patriarch Joachim was the husband of St. Anne and the father of our Lady. This feast, originally kept on March 20th, was tranferred to the day after the Assumption in order to associate the Blessed Daughter and her holy father in triumph.

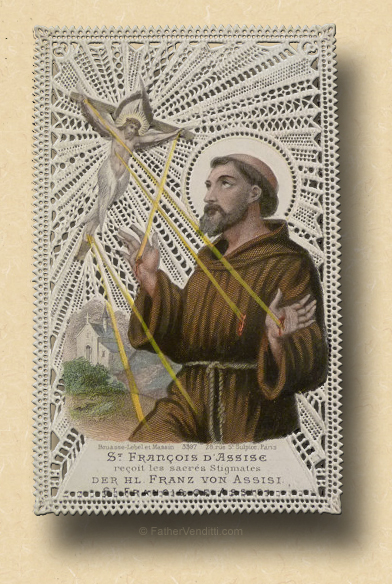

*** The "Icon Not Made with Human Hands" is the popular designation for an icon which is more properly called "The Holy Napkin," which depicts a cloth on which is imprinted the face of Jesus, and is often misunderstood by Christians both in the East and the West. Roman Catholics usually mistake it for an image of "Veronica's Veil," while Eastern Christians often make the mistake of thinking that it's popular title of being "Not Made with Human Hands" refers to the original of the icon being somehow miraculously created. Both are false. The icon is, in fact, a representation of the napkin mentioned in John's account of the Resurrection: "Simon Peter, coming up after him, went into the tomb and saw the linen cloths lying there, and also the veil which had been put over Jesus’ head, not lying with the linen cloths, but still wrapped round and round in a place by itself" (20: 6-7 Knox). It is "Not Made by Human Hands" because the icon seeks to depict a mirculous residual effect of our Lord's resurrection, but was most certainly written by a human iconographer.

The feast commemorates the transfer of the original icon from Edessa to Contantinople in the year 944.

|