Forsake Foolishness that You May Live.

The Twentieth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the secondary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Proverbs 9: 1-6.

• Psalm 34: 2-7.

• Ephesians 5: 15-20.

• John 6: 51-58.

The Twelfth Sunday after Pentecost.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• II Corinthians 3: 4-9.

• Psalm 33: 2-3.

• Luke 10: 23-37.

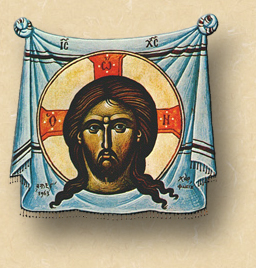

The Twelfth Sunday after Pentecost; a Postfestive Day of the Dormition; the Feast of the Translation of the Icon of Christ Not Made by Human Hands; and, the Feast of the Holy Martyr Diomedes.

First & third lessons from the pentecostarion, second & fourth lessons from the menaion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:*

• I Corinthians 15: 1-11.

• II Corinthians 3: 4-11; or, Colossians 1: 12-18.

• Matthew 19: 16-26.

• Luke 9: 51-56; 10: 22-24.

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:44 AM 8/16/2015 — I apologize for us being cramped into this small space today. It was not my idea to accept a last minute request from some group to use our Shrine upstairs for a noon Mass on a Sunday; but, as I keep pointing out to people when they come to me with their complaints about various things, I'm not in charge. People sometimes have a hard time with that concept: they assume that if some place has a priest in it, then the priest must be in charge. I guess that makes this place unique, in that here the priest is the low man on the totem pole. Actually, it's more proper to say the high man on the totem pole, since, if you ask Father Paul, who spent some years as pastor on an Indian reservation, on a genuine totem pole, the important figures are on the bottom, and get less important as you go up, with the least important person being on the top. So, here, I'm the top man on the totem pole. 8:44 AM 8/16/2015 — I apologize for us being cramped into this small space today. It was not my idea to accept a last minute request from some group to use our Shrine upstairs for a noon Mass on a Sunday; but, as I keep pointing out to people when they come to me with their complaints about various things, I'm not in charge. People sometimes have a hard time with that concept: they assume that if some place has a priest in it, then the priest must be in charge. I guess that makes this place unique, in that here the priest is the low man on the totem pole. Actually, it's more proper to say the high man on the totem pole, since, if you ask Father Paul, who spent some years as pastor on an Indian reservation, on a genuine totem pole, the important figures are on the bottom, and get less important as you go up, with the least important person being on the top. So, here, I'm the top man on the totem pole.

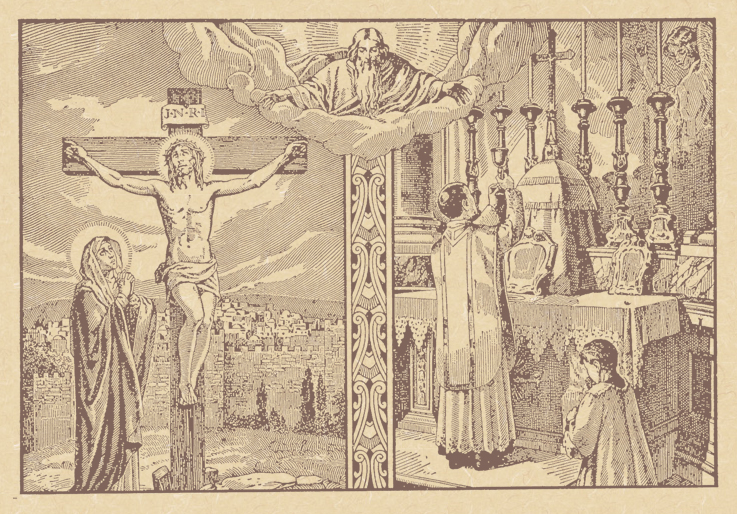

Anyway, this is clearly off the mark. And since I'm clearly in a sour mood, I'm going to share my misery by asking you to do something very difficult, and that's to think back over the past few weeks about the Scripture lessons we've been given to hear during these summer Sundays. It's a tall order because we simply don't train ourselves to do it, most of us. We come to Mass and just assume that each Sunday's Mass is an entity in and of itself; but, we've been following a general theme the past few weeks, beginning with our Blessed Lord feeding five thousand people on the hillside with five loaves and two fish on the Seventeenth Sunday back at the end of July; clearly, a prefiguring of the Blessed Eucharist. On the Eighteenth Sunday, our Gospel lesson picked up right where that one left off, with our Lord being followed by the crowd He had fed, and castigating them for not understanding the meaning of the miracle he performed, and just looking for another free meal, but from which we were able to reflect on the importance of making sure that we are properly disposed and worthy to receive Holy Communion. And, finally, in the Nineteenth Sunday, we read about how the Prophet Elijah, fleeing Jezabel, sets out for the Holy Mountain of God and, tired from his journey, is strengthened and renewed by an angel who brings him bread, coupled with a Gospel lesson in which our Lord makes, at the very end of the Gospel lesson, the most profound statement He will make about the Eucharist:

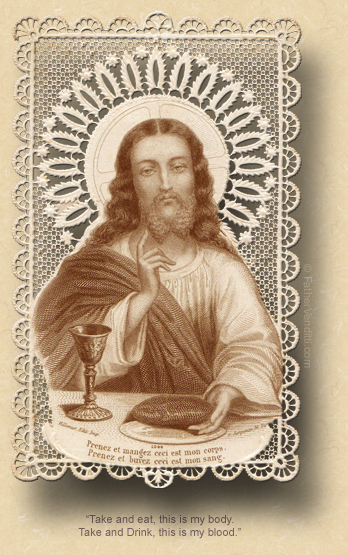

I myself am the living bread that has come down from heaven. If anyone eats of this bread, he shall live for ever. And now, what is this bread which I am to give? It is my flesh, given for the life of the world (John 6: 51-52 Knox).

And today's Gospel lesson again picks up right where that one left off, with that last verse of last Sunday's Gospel being repeated for us at the very beginning of today's. So, clearly, the liturgy of the Church this time of year is focusing us on this Eucharistic theme. Our Lord today clarifies even more about the Blessed Eucharist, emphasizing the necessity of worthily receiving Holy Communion in order to attain eternal salvation, and pointedly reminding us, at the same time, that the Blessed Eucharist is not merely a symbol of Him, but is real in every respect: “My flesh is real food, my blood is real drink. He who eats my flesh, and drinks my blood, lives continually in me, and I in him” (6: 56-57 Knox).

What our Lord is actually doing here is defining, in a very elementary way, what the Church calls the dogma of Transubstantiation, which is a big sounding word that most of you may remember from your childhood catechism, but which is very easy to misunderstand. I've found that the best way to explain Transubstantiation is by comparing it with its opposite, which is transformation, a much more familiar word. What does it mean to transform something? Break down the word: “trans” means to change, “form” means what it looks like or what form it takes. Take water, for example: it's composed of two elements, hydrogen and oxygen. Expose it to extreme cold, and it freezes and becomes a solid; boil it, and it evaporates and becomes a gas; leave it alone and it remains a liquid; but, in each case, it's elemental structure remains the same. It's H2O, regardless of what form it takes.

Transubstantiation is just the opposite, and I can't give you an analogy for it because the only example of it in nature is the Blessed Eucharist. The priest pronounces over bread and wine the words of Christ, “This is my body. This is my blood.” We don't see anything happen because the form of them remains unchanged; it's the substance of them which has changed. Unlike the water, which can take different forms while remaining the same thing, the bread and wine on the altar actually have their substance changed while their form remains the same. We approach for Holy Communion and look upon the Sacred Host; it looks like bread.  If we receive in the hand, as some do, it feels like bread. When it is placed on our tongue, it tastes like bread. But it's not bread: the substance of it has been changed completely. We don't give Holy Communion under both species here at the Shrine, but I'm sure most of you have received from the chalice before in your parishes; and, when you do, you know what it tastes like: it tastes like wine, and very bad wine at that. Most altar wines produced today for Mass are notoriously bad. But it certainly doesn't taste like blood. But the fact is, it is blood. It's form remains that of wine, but it's substance has been completely changed. If we receive in the hand, as some do, it feels like bread. When it is placed on our tongue, it tastes like bread. But it's not bread: the substance of it has been changed completely. We don't give Holy Communion under both species here at the Shrine, but I'm sure most of you have received from the chalice before in your parishes; and, when you do, you know what it tastes like: it tastes like wine, and very bad wine at that. Most altar wines produced today for Mass are notoriously bad. But it certainly doesn't taste like blood. But the fact is, it is blood. It's form remains that of wine, but it's substance has been completely changed.

In point of fact, in the mystery of Transubstantiation, both species become both the Body and Blood of the Lord, which is why it's never necessary to receive under both kinds, because once you've received the Sacred Host, you've already received both the Body and Blood of the Lord; the custom of giving Communion under both kinds is purely for symbolic value, since in either form the whole of Christ is present. There are some people who suffer from a very rare disease which makes it impossible for them to eat any kind of solid food, and when these people receive Holy Communion, they are given Communion only from the chalice because they cannot receive the Host; but, when they receive from the chalice, they receive the whole of Christ, just as you do when you receive only the Host.

Now, this may all seem very esoteric and unnecessarily technical to you, but you must understand how important this is. The Blessed Sacrament is Jesus. It's not a symbol of Jesus. It's not a sign of Jesus. Jesus is not present in the bread and wine. It actually is the Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of Jesus Christ, and Jesus Christ is God. This is why non-Catholics cannot receive Holy Communion, and why even Catholics must be in the state of grace to receive. When I was a young priest—three or four hundred years ago—my pastor at the time, who was one of these shell-shocked old guys who had been totally confused by the Second Vatican Council, made me participate in these regular ecumenical meetings with all the Protestant pastors in town, and every time we had a meeting they would all berate me because we would not invite them to receive Holy Communion in our church. But Protestants don't believe in Transubstantiation, nor could they make it happen even if they did because they do not have a valid priesthood. For them, the Eucharist is nothing but fellowship; it's purpose is simply to show our unity with one another; it's not a sacramental reality for them.

But, even for ourselves as Catholics, we have to be conscious of what's happening at Holy Mass, and especially when we approach for Holy Communion. Taking into ourselves the Body and Blood of the Lord can be a great grace—as our Lord says in today's Gospel, “The man who eats my flesh and drinks my blood enjoys eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day” (6: 55 Knox)—but grace can only operate in a soul which is properly disposed. If we receive Holy Communion knowing that we are unworthy to receive it, not only do we not receive any grace, but, as the Church has continually taught, we commit a mortal sin of sacrilege. That's why it's so important to examine our conscience whenever we intend to receive; and, if we are conscious of any mortal sin, then we must not receive until we have gone to confession. Not receiving Holy Communion is not nearly as dangerous to our souls as receiving Him unworthily.

I know this has been a very dry homily and much more informative than inspiring; but, once in a while the basics of our Catholic Faith need to be repeated, especially in this day and age when so many Catholics are lacking any real knowledge of their faith. Today's first lesson was taken from the Book of Proverbs, itself a rather strange and dry collection of home-spun wisdom which hardly rises to the level of profound theological truth, but the word of God nonetheless. And the last two verses of that reading combine two ideas which seem, on the surface, to have nothing to do with one another, but which, in the context of all we've been considering, actually become very profound: “Come, eat of my food, and drink of the wine I have mixed! Forsake foolishness that you may live; advance in the way of understanding” (9: 5-6 NABRE).

* The first & third lessons are for the Sunday, the second & fourth for the feast of the Icon. There are no lessons for the martyr. * The first & third lessons are for the Sunday, the second & fourth for the feast of the Icon. There are no lessons for the martyr.

The "Icon Not Made with Human Hands" is the popular designation for an icon which is more properly called "The Holy Napkin," which depicts a cloth on which is imprinted the face of Jesus, and is often misunderstood by Christians both in the East and the West. Roman Catholics usually mistake it for an image of "Veronica's Veil," while Eastern Christians often make the mistake of thinking that it's popular title of being "Not Made with Human Hands" refers to the original of the icon being somehow miraculously created. Both are false. The icon is, in fact, a representation of the napkin mentioned in John's account of the Resurrection: "Simon Peter, coming up after him, went into the tomb and saw the linen cloths lying there, and also the veil which had been put over Jesus’ head, not lying with the linen cloths, but still wrapped round and round in a place by itself" (20: 6-7 Knox). It is "Not Made by Human Hands" because the icon seeks to depict a mirculous residual effect of our Lord's resurrection.

The feast commemorates the transfer of the original icon from Edessa to Contantinople in the year 944.

|