"Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us."1 Cor. 9:2-12;

Matt. 18:23-35. The Eleventh Sunday after Pentecost. A Postfestive Day of the Transfiguration. The Holy Martyrs Photius & Anicetus. Our Holy Father Maximos the Confessor is also celebrated today since tomorrow is the Leave-taking of the Transfiguration.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

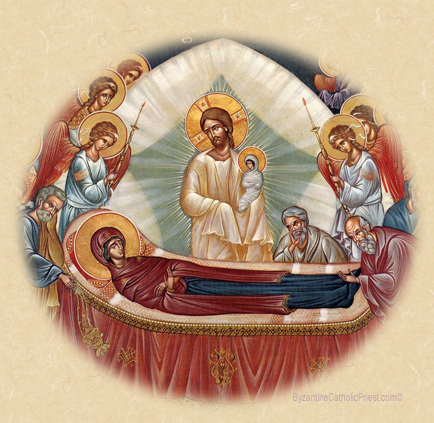

12:04 PM 8/12/2012 — This week we will celebrate the great feast of the Dormition or “falling asleep” of the Theotokos; and, because I don’t preach on Holy Days, I would like to say just a few words about it before diving into today’s Gospel lesson.

The Dormition, of course, is a feast of the Mother of God. It commemorates her being taken up into heaven. If you grew up following the calendar of the Roman Church, like I did, you probably would have referred to it as the Assumption. It means basically the same thing. The difference, of course, lies in the fact that the feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God was being celebrated in the Eastern Churches a thousand years before Pope Pius XII defined the dogma of the Assumption in 1950. In fact, there’s some evidence to suggest that the Church in the West, too, celebrated the falling asleep of the Mother of God early on, but dropped the feast until the definition of the Dogma. And it’s meaning is relatively simple to understand. The Dormition, of course, is a feast of the Mother of God. It commemorates her being taken up into heaven. If you grew up following the calendar of the Roman Church, like I did, you probably would have referred to it as the Assumption. It means basically the same thing. The difference, of course, lies in the fact that the feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God was being celebrated in the Eastern Churches a thousand years before Pope Pius XII defined the dogma of the Assumption in 1950. In fact, there’s some evidence to suggest that the Church in the West, too, celebrated the falling asleep of the Mother of God early on, but dropped the feast until the definition of the Dogma. And it’s meaning is relatively simple to understand.

The Book of Genesis teaches us that mankind, because of the original sin he inherits from his first parents, is subject to mortal shortcomings despite the fact that he has an immortal soul; one of these shortcomings is the death of the body. But the Mother of God, because of her Immaculate Conception, does not have original sin and, therefore, is not subject to the shortcomings which are the result of it. And so it is the faith of the Church that Mary, at which would have been the moment of her death, was spared the suffering of death—and the separation of soul and body which is the result of death—and instead was permitted to enter heaven complete, with both her body and soul intact. It’s an important dogma with lots of implications about what we believe as Christians about the end of our lives and what will happen to us when we pass from this world.

But rather than go into all of that, I would like instead to focus our attention on the Gospel passage of this Sunday: our Lord’s parable about the servant who is forgiven but who refuses to forgive. It is an illustration of that part of the Lord’s Prayer in which we pray, “Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us....” And it’s very easy to misunderstand because it gives the impression that one is the cause of the other: that God will forgive us because we have forgiven others. But the parable that we read today gives a very different explanation.

When the servant refuses to forgive the debt of his fellow servant, and his employer comes down on him, why is the employer so upset? What business is it of his? Well, it’s his business because the servant whom he forgave of a much larger debt wouldn’t even be around to forgive anyone himself if the employer had treated him the same way. In other words, the forgiveness of the employer to the first servant should have been continued by the first servant to the second servant, but it wasn’t. It is a feature of Christian forgiveness that is found in no other religious system, and applies to the whole subject of grace as understood by the Catholic Churches.

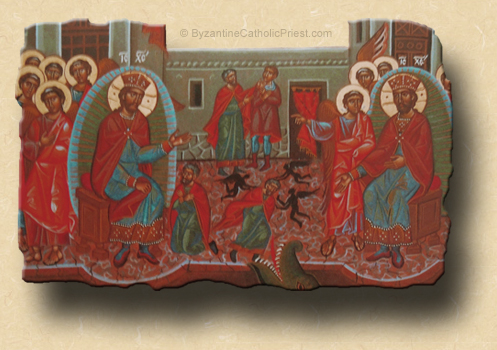

I use to listen sometimes to Dr. Laura on the radio. She’s was this person who would try to give advice to people she’s never met;—I’m not even sure if she’s still on the air—she’s not a Christian, she’s a convert to the Jewish Faith. And her notion of forgiveness is a very classical Jewish notion. So, women would call her up, for example, and tell her that their husbands have been unfaithful or they caught them looking at dirty pictures on the Internet or something, or how some relative or other did something to hurt them, and they’ll ask if they should forgive. And invariably she would respond by saying that forgiveness requires some kind of recompense: that you can’t forgive someone until they’ve made amends. It’s the classical Jewish point of view: an eye for an eye; forgiveness requires reciprocity. But the parable told by our Lord says something quite different, and I can only imagine how it must have shocked his Jewish audience, because the employer in the story initially takes a classical Jewish point of view: he wants to sell the servant and his family into slavery until his debt is paid off, and only after it’s paid off will he release him. According to the laws set down in the book of Leviticus in the Old Testament, this is what he is supposed to do. But the employer doesn’t stick to it. He feels sorry for his servant and, because the servant pleads with him for the sake of his family, he lets him off the hook completely, so much so that now he doesn’t have to pay the money back at all.

Now, Dr. Laura would probably say that the employer is being a "weenie," that there is no need for him to act this way, and if the servant is worried about his family.... Well, he should have thought of that before he defaulted on the loan. Our Lord, in telling this story, is taking a very deliberate swipe at the classical Jewish notion of justice and reciprocity.  Later on in his public preaching he would do it even more directly: “If a man strikes you on one cheek, turn to him the other.... If someone takes your coat, give him your shirt as well.... Love those who hate you, and do good to those who persecute you....” Clearly, our Lord is turning his back on traditional Old Testament teaching about justice and replacing it with something completely different. The question is, what is he replacing it with? Later on in his public preaching he would do it even more directly: “If a man strikes you on one cheek, turn to him the other.... If someone takes your coat, give him your shirt as well.... Love those who hate you, and do good to those who persecute you....” Clearly, our Lord is turning his back on traditional Old Testament teaching about justice and replacing it with something completely different. The question is, what is he replacing it with?

To answer that, we have to look at the second part of the parable, in which the servant who has been forgiven is faced with a similar situation regarding something owed to him. When the second servant, who owes the first servant money, is unable to pay it, he’s put in prison. The first servant refuses to forgive him. He would have made Dr. Laura proud. According to the Old Testament, what he has done is completely justified. But the employer of them both is furious. Why? Why is it any of his business? And here is the precise point where Christian social teaching departs from Judaism. The employer is furious because the forgiveness that he gave the first servant, the first servant has failed to pass on to another. In other words, all grace, but especially the grace of the forgiveness of our sins, comes from Christ, bought with the price of his blood upon the cross; and, when we forgive others, we are not giving something of our own which is in our power to give; we are merely passing on the forgiveness of Christ which we have already received.

When someone comes into the confessional and says to the priest, “Father, I committed adultery,” and the priest says, “Well, say four Our Fathers and Four Hail Marys,” does anyone really believe that those four Our Fathers and four Hail Marys make up for the sin of cheating on your spouse? Of course not. If the penance was supposed to be an actual retribution for the sin, then the priest would have to have you flogged in the public square. The penance is just a symbol for our benefit so that we know, when we’ve sinned, that a retribution has been made. But that retribution is not the measly penance that you’re given; the retribution for your sin is Christ being nailed on a cross. That’s the consequence of your sin; not just the possible human consequences of embarrassment or betrayal that might result.

Sometimes you’ll hear people say that what they’re doing—whatever it may be—isn’t really a sin because it’s not hurting anyone. It’s a very common notion today. But the reason Christians don’t accept that is because sin always has a victim. So, I can’t say, for example, that my sin, whatever it is, didn’t hurt anyone. It did hurt someone. Being nailed to a cross hurts.

The point, of course, that our Lord is trying to make in his parable is that when someone wrongs us, and we have an opportunity to either forgive them or not to forgive them, for the Christian it isn’t a question of justice or reciprocity, because the forgiveness we might offer them is not really ours to give or not to give. The forgiveness is Christ’s. We are simply passing it on. And if we refuse to pass it on, then we are rejecting it for ourselves. That’s why the servant in the parable, who had already been forgiven by his employer, when he refused to forgive his fellow servant, had it taken away from himself and was thrown into prison. He wasn’t simply refusing to give something that belonged to him; he was refusing to pass on what he had received freely as a gift.

“Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.” We pray it so many times every day. It doesn’t mean, “If I forgive others, then I will be forgiven.” It means, “I have been forgiven, therefore I must forgive others.”

Father Michael Venditti

|