The Teahouse of the August Moon.*1 Corinthians 15:1-11;

Matthew 19:16-26. The Twelfth Sunday after Pentecost. A Postfestive Day of the Transfiguration. The Holy Martyr Euplus.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

12:51 PM 8/11/2013 — I had toyed with the idea of preaching today on the Dormition of the Theotokos, since we will celebrate it this week; and, since it's a Day of Precept, and since I usually don't preach on Holy Days, I thought it would make a good advertisement for your attendance. I also have been very self-conscious about repeating myself, especially with a Gospel lesson like this one, which appeals to me so much; plus the fact that, in looking back in my files, I realize that the last time I preached to you about the Dormition was back in 2006, which is quite long enough. So, I initially prepared a homily on the Dormition; but, the temptation of this Gospel is just too strong for me; so, you'll be getting a special treat this week, as I will actually preach about the Dormition on the feast of the Dormition.

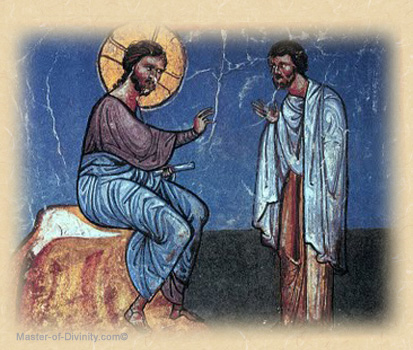

Now, as you've heard me say before, this young man in today's Gospel is an interesting case because he’s so completely human; we can see ourselves in him on so many levels. Put yourself for a moment in his shoes. What would each of us ask our Lord if we should chance to meet him face to face? I should like to think we would ask the same question he does, as it's the most quintessential question a man can ask: “What must I do to be saved.” Our Lord’s answer is as simple and as complete as the question, and it doesn’t surprise us because we’ve seen him give this answer many times: “Keep the Commandments.” But he wants more than that. He wants to join our Lord and become a disciple. Our Lord gives him that chance, but first explains to him what he must give up to make that happen, as he would be obligated to do.

You may recall a couple of years ago, when we looked at this Gospel lesson about the rich young man, we compared him with the rabbi at the beginning of the parable of the Good Samaritan, how they both ask our Lord the same question, and how they both get from our Lord the same simple answer. Each of them reacts to our Lord’s answer differently because each one has a different motive in asking the question. The rabbi wants to justify himself; the rich young man sincerely wants to do more out of the generosity of his heart. And you may recall that we recognized the fact that what our Lord asks of the young man—to sell all his possessions and give the money to the poor—was what he asked of the original Twelve Apostles. The young man goes away sad because he’s not willing to do those things, and it's not hard to understand what’s happened to him here.

He’s obviously been following our Lord around for some time, and has been very much impressed. He’s got money, which means he’s probably lived a very sheltered life, and never been exposed to any kind of cause to which he might want to dedicate himself.  Jesus comes along and ignites in him a youthful vigor for something to give his life meaning, and he allows himself to be caught up emotionally. He sees the camaraderie between Jesus and his disciples, and he wants to be a part of it, but his emotional needs are not matched by the will to actually do what is required to fulfill them. His emotional attraction to the whole “Jesus thing” has blinded him to the fact that, in reality, he’s not ready for the kind of commitment that is needed for him to actually join Jesus and become one of his disciples. Jesus comes along and ignites in him a youthful vigor for something to give his life meaning, and he allows himself to be caught up emotionally. He sees the camaraderie between Jesus and his disciples, and he wants to be a part of it, but his emotional needs are not matched by the will to actually do what is required to fulfill them. His emotional attraction to the whole “Jesus thing” has blinded him to the fact that, in reality, he’s not ready for the kind of commitment that is needed for him to actually join Jesus and become one of his disciples.

Some years ago, a young couple came to me to get married. They were both eighteen and had just graduated high school. Everyone they knew was opposed to this marriage, not because anyone had a problem with either of them, but simply because they were too young. The fly in the ointment was the fact that they were of age and didn’t legally need anyone’s permission to marry. And both families were very shocked and angry when I seemed to welcome them with enthusiasm and began to make plans with them for this grand wedding they wanted. What they didn’t realize was that Father wasn’t born yesterday. In the course of our marriage instruction, I began, very subtly, to focus their attention on some seemingly mundane and pragmatic things: like creating a home, what kind of meals to prepare for children at certain ages, when a child should be allowed to have his or her own room, how to choose a school, how you might have to take a job you don’t want because you have other people dependent on you, how to save for your children’s college education, how to create an environment of security that will enable children to grow up happy and well-adjusted—all the things that teenagers in love never think about. And two weeks didn't go by before the girl came to me privately and said, “Father, I’m not ready for this.”

Now, if I had taken the line that the families wanted me to take, and simply told them that they were too young and needed to wait, they probably would have stormed off angrily, gotten married before a Justice of the Peace, and made a mistake they would regret the rest of their lives. The reality of what they were asking me to do for them had finally caught up with the romantic emotions that brought them to me in the first place.

When my mother sold the house where I grew up and moved into a retirement community, she handed me a box of all kinds of junk that I had left in the house thirty years before; and among this were yearbooks and photographs from my early seminary days in Kentucky; I still have them. And as I paged through them, I realized that most of the people in those pictures never became priests. Every young man who enters the seminary gets attracted to the priesthood on an emotional level, probably inspired by a priest he knew growing up who had an impact on him. But it takes a number of years before reality catches up with the emotion. It wasn’t a mistake for them to go to the seminary;—if they had not gone there, they would have spent their whole lives wondering if they should have—but, it wasn’t until they actually learned first hand what sacrifices are required that they were able to decide if that’s what God was really calling them to do. Their years in the seminary were far from wasted.

When our Lord asked the rich young man to sell everything he had and follow him, he knew the young man wasn’t ready. He asked him anyway because he knew that it was the only way to force the young man to come face to face with the reality of his life. Unfortunately, the Gospel passage ends with the young man walking away sad, but that doesn’t mean that he walked away for good. For all we know, he grew up to develop a whole new set of priorities, and, after our Lord’s resurrection, may have become a passionate member of the early Church.

The lesson for us here is that the sadness he felt as he walked away was not necessarily a bad thing. Pain makes us think. And when we encounter pain in our lives because we feel we’ve been denied something we want very badly, maybe it’s time to sit down and consider what it is that our Lord is asking us to think about.

* The extraneous title given to this homily is the title of one of my favorite films, about the American occupation of Okinawa, which ends with the line: "Pain makes us think; thought makes us wise; wisdom makes life endurable." I use it because I found myself unconsciously using part of that line in the last paragraph of the homily.

|