He Has Counted Every Hair of Your Head (Unless You're Bald Like Me, in Which Case He Must Count Something Else).

The Fourteenth Saturday of Ordinary Time; the Memorial of Saint Agustine Zhao Rong, Priest, & Companions, Martyrs; or, the Memorial of the Blessed Virgin Mary on Saturday.

Lessons from the secondary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Isaiah 6: 1-8.

• Psalm 93: 1-2, 5.

• Matthew 10: 24-33.

|

If the lessons from the proper are taken:

• I John 5: 1-5.

• Psalm 126: 1-6.

• John 12: 24-26.

…or any lessons from the common.

|

The Fourth Class Feria of the Blessed Virgin Mary on Saturday.

Lessons from the common, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ecclesiasticus 24: 14-16.

• [Gradual] Benedícta et venerábilis es…*

• Luke 11: 27-28.

|

If the Mass for the seasonal votive is taken, the first lesson as follows, the rest as above:

• Ecclesiasticus 24: 23-31.

|

The Seventh Saturday after Pentecost; and, the Feast of the Holy Martyr Pancratius, Bishop of Taormina.**

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Romans 13: 1-10.

• Matthew 12: 30-37.

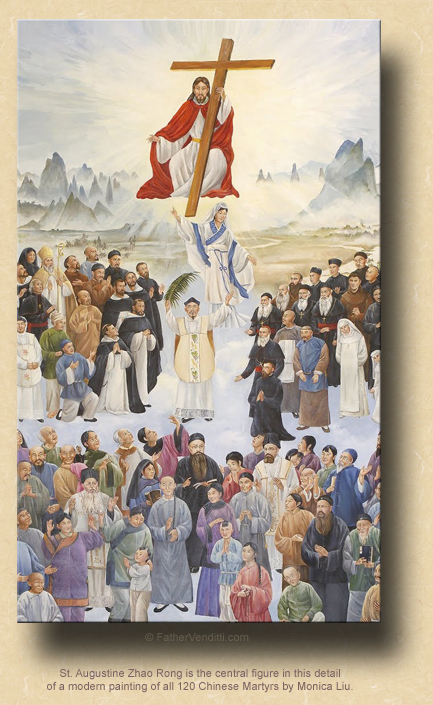

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:37 AM 7/9/2016 — I know it's a long shot, but you might remember some time ago, on Trinity Sunday at the beginning of the summer, I had spoken about how angels operate whenever they function as messengers of God. In the New Testament, usually they speak with their own voices, as in the case of the Archangel Gabriel's two recorded appearances: first to Zachariah, where he actually identifies himself by name, saying, “I am Gabriel,” and to the Mother of God at the Annunciation where he also speaks with his own voice. In the Old Testament, the angels would often—though not always—speak with God's voice, functioning almost like mobile loud speakers: they open their mouths, but it's the voice of God which comes out, as in the case of the angel sent to Elijah, and in the particular instance we were considering that day, when God sent three angels to represent all three persons in the Blessed Trinity to deliver His word to Abraham. 8:37 AM 7/9/2016 — I know it's a long shot, but you might remember some time ago, on Trinity Sunday at the beginning of the summer, I had spoken about how angels operate whenever they function as messengers of God. In the New Testament, usually they speak with their own voices, as in the case of the Archangel Gabriel's two recorded appearances: first to Zachariah, where he actually identifies himself by name, saying, “I am Gabriel,” and to the Mother of God at the Annunciation where he also speaks with his own voice. In the Old Testament, the angels would often—though not always—speak with God's voice, functioning almost like mobile loud speakers: they open their mouths, but it's the voice of God which comes out, as in the case of the angel sent to Elijah, and in the particular instance we were considering that day, when God sent three angels to represent all three persons in the Blessed Trinity to deliver His word to Abraham.

Today, in the first lesson, we are presented with God's initial contact with the greatest of the Old Testament prophets, the Holy Prophet Isaiah; and, as you would expect, the angels sent to him speak with the voice of God. Isaiah describes the encounter in surprisingly vivid detail; he even identifies the particular choir of angels from which they come: the Seraphim. He doesn't tell us how many there are, but he does tell us that each of them has six wings: two they use to veil their faces, two to cover their feet, and two with which they fly.*** When they appear, they're singing, and what they sing so struck the Fathers of the Church of the first four centuries that it became part of the liturgy of the Church: “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God of hosts; all the earth is full of his glory” (6: 3 Knox); it's part of the Te Deum sung at Matins and, as you know, part of the Mass itself.

The message they bring to the prophet is pretty much the same that we've been reading about in other circumstances all through the summer: God made a covenant with his people but, over the course of time, it was forgotten, so God sends someone to call His people back to the life of the Commandments. Isaiah's problem with this is that he feels he's not worthy to bear such a message being that he's just as unclean as the rest of God's people: “Woe is me, I am doomed!” he says, “For I am a man of unclean lips, living among a people of unclean lips...” (6: 5 RM3); upon which follows that painful sounding episode where one of the angels brings over a hot coal with tongs—so it's even too hot for the angel to handle—and touches it to the prophet's lips. We cringe when we read those words; but after, the angel tells him, “Now that this has touched thy lips, thy guilt is swept away, thy sin pardoned” (6: 7 Knox). Just as an aside, in the Byzantine Rite, after the priest has received from the chalice, he repeats those very words.

What's important here is that, after suffering this purging ritual, Isaiah now believes himself worthy to deliver God's message of repentance to the people of Israel, and it provides us with a way to contextualize our own suffering and the many crosses we bear in our daily spiritual combat. Many times you've heard me speak of the concept of God's permissive will: that God doesn't desire us to suffer, but often allows us to suffer for a reason unknown to us; and here is revealed one of the possible reasons: God allows a cross to come our way in order to purify us in anticipation of some task we are to perform for Him.

Our Lord tells us as much: in today's Gospel lesson he reminds us that no suffering is allowed to come our way without a purpose; it's just that the purpose is not often revealed to us, which then becomes a test of faith for us. Nevertheless, we must go forth unafraid, He says, and spread the message of salvation to everyone we meet without fear.

Today's memorial, which is a very unusual one, makes the point even clearer: the calendar of the Latin Church honors on this day one hundred twenty martyrs who died in China in scattered intervals between 1648 and 1930. Eighty-seven of them were born in China, and included children as young as nine, and men and women as old as seventy-two. Included among them were four Chinese priests. Thirty-three of them were foreign born missionaries working in China, from a variety of different religious congregations: the Paris Foreign Mission Society, the Franciscans, the Jesuits, the Salesians, the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary, and including the Dominican Priest Saint Francis Capillas, who is regarded as the proto-Martyr of China; he was killed on January 15th, 1648. Today's memorial, which is a very unusual one, makes the point even clearer: the calendar of the Latin Church honors on this day one hundred twenty martyrs who died in China in scattered intervals between 1648 and 1930. Eighty-seven of them were born in China, and included children as young as nine, and men and women as old as seventy-two. Included among them were four Chinese priests. Thirty-three of them were foreign born missionaries working in China, from a variety of different religious congregations: the Paris Foreign Mission Society, the Franciscans, the Jesuits, the Salesians, the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary, and including the Dominican Priest Saint Francis Capillas, who is regarded as the proto-Martyr of China; he was killed on January 15th, 1648.

The one man whose name is mentioned in the Collect of today's Mass, Saint Augustine Zhao Rong, was originally a soldier who had been assigned to guard Bishop John Gabriel Taurin Dufresse of the Paris Foreign Mission Society and escort him to his execution when the time came for him to give his life for Christ. He was so moved by the bishop's courage that he later sought baptism, and not long after that was ordained a secular priest; he, himself, was martyred in 1815.

Over the next one hundred years, all of these people would be beatified in groups at various times, but all one hundred twenty of them were canonized together on October 1st, 2000, by Pope Saint John Paul II. It's the only time that I can remember that so many people, who died over so long a period, were all canonized at one time.

Of course, the Church in China continues to suffer to this day, and there are martyrdoms taking place there every day, martyrdoms that we may never know about until, perhaps, a hundred years from now.

Most of the saints we honor today probably didn't know one another; they were bound together not by social interaction but by a common faith and a desire to bring their country to salvation through Christ. And while there are optional readings I could have chosen for their feast related to missionaries and martyrs, I chose instead to stick to the readings of the day, the Gospel of which puts into context the whole subject of God's permissive will and the role of the Cross in the life of every Christian. The challenge it presents to us is to succeed in separating our emotions from the confidence of our faith, and push on with the task even when we don't feel the presence or protection of God:

Are not sparrows sold two for a penny? And yet it is impossible for one of them to fall to the ground without your heavenly Father’s will. And as for you, he takes every hair of your head into his reckoning. Do not be afraid, then; you count for more than a host of sparrows (Matt. 10:29-31 Knox).

We may think that we don't have much in common with these one hundred twenty martyrs of China, but we're wrong. There are many different kinds of martyrdom: not just martyrdom of blood, but also martyrdom of mind, martyrdom of loneliness, martyrdom of despair and desperation. I'm not suggesting that we're worthy of canonization if we spend a good part of our lives depressed; I am suggesting that, as we suffer the many crosses that the Lord, in His permissive will, allows to come our way for whatever reason, we could do worse than to ask these one hundred twenty brave souls for their spiritual help. Given the almost unfathomable courage with which these people—many of whom, as I said, were children—went to their deaths, I can only suppose that their intercession carries great influence before the Throne of Christ our true God.

* The Gradual is non-Scriptural: "Blessed and venerable are You, O Virgin Mary, Who, with unsullied virginity, were found to be the Mother of the Savior. O Virgin, Mother of God, He Whom the whole world does not contain, becoming Man, shut Himself in Your womb. Alleluia, alleluia. After childbirth You remained a pure virgin, O Mother of God, intercede for us. Alleluia."

** Information about the Holy Hieromartyr Pancratius is sketchy at best, except that he existed and is dated to the time of the Apostles. Probably from Antioch, he became the first bishop of Taormina in Sicily, where he died a martyr's death. The troparion for his feast speaks of him being a follower of the Apostles, known for a life of contemplation, who shed his blood for having taught the truth.

*** There is a discrepancy between the Greek text and that of the Latin Vulgate. The Greek reads: “καὶ σεραφιν εἱστήκεισαν κύκλῳ αὐτοῦ ἓξ πτέρυγες τῷ ἑνὶ καὶ ἓξ πτέρυγες τῷ ἑνί καὶ ταῖς μὲν δυσὶν κατεκάλυπτον τὸ πρόσωπον καὶ ταῖς δυσὶν κατεκάλυπτον τοὺς πόδας καὶ ταῖς δυσὶν ἐπέταντο...” (6: 2), which would indicate that the Seraphim covered their own faces and feet, whereas the Latin text reads: “Seraphim stabant super illud: sex alæ uni, et sex alæ alteri; duabus velabant faciem ejus, et duabus velabant pedes ejus, et duabus volabant,” which seems to indicate that the wings covered the face and feet of God, Himself. Msgr. Knox notes both senses in a footnote, but retains the sense of the Latin text in his translation: “…with two wings they veiled God’s face, with two his feet, and the other two kept them poised in flight..,” whereas the Roman Missal Third Edition gives the sense of the Greek text: “…with two they veiled their faces, with two they veiled their feet, and with two they hovered aloft.”

|