The Divine Liturgy, Part Seven: A Psalm by Any Other Name; or, The Eastern Churches' Notre Dame. The Troparion & the Kontakion.Rom. 15:1-7; Matt. 9:27-35. The Seventh Sunday after Pentecost, kown as The Seventh Sunday of Matthew. A Prefestive Day of the Procession of the Venerable & Life-creating Cross.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

11:03 AM 7/31/2011 — The preparation rites, the Litany of Peace, the antiphons, the Little Entrance.... We seem to be moving right along; which is deceptive; because, if we keep moving at this pace we’ll still never finish by the end of the summer. But push on we must. Which pushes us right into another one of those parts of the Divine Liturgy which is so familiar to us even though what we know of it’s origins or meaning is incomplete: in this case, the Troparia and Kontakia. In pigeon Slavonic we often call them simply Tropars and Kondaks. They are, of course, hymns; and—like most early Christian hymns—their origin goes back to the ancient Hebrews and the Psalms.

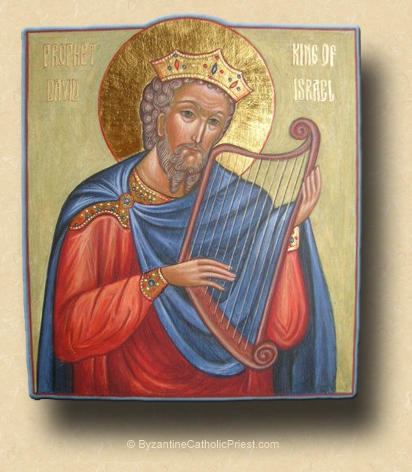

From the days of the Apostles themselves, the Psalms of David were used as hymns by the early Christians, as they are still today—in case you haven’t noticed, the liturgical services of our Church (and all Eastern Churches) are laced through and through with Psalms. The antiphons, which we looked at two weeks ago, are a good example. But, remember that the Psalms are from the Old Testament. Now, according to the early Christians, the entire Old Testament points to the advent of Christ; and many of the early Fathers of the Church—Basil the Great, Augustine, Cyril of Alexandria and, of course, John Chrysostom himself—spent a lot of time and a lot of sermons explaining the true meaning of the Old Testament books in light of Christ. Where the Psalms were concerned, they were being used as hymns in church; but the early Fathers wanted to make sure that the people singing them knew how they related to Christ. So, beginning in the third century, many of these ancient Fathers began to compose little explanations for each Psalm in the form of refrains which were added to the beginning and end of the Psalm. As time went on, hymnographers in the Church began to compose a variety of refrains for each Psalm for various feasts or occasions: Christmas, Easter, Theophany, Dormition; and as the number and variety of feasts and celebrations grew in the Church, so did the variety and number of refrains added to the beginning and end of each Psalm to show how that Psalm could be sung in honor of that particular feast.

Now, when you look at a Troparion or Kontakion today, you might very well ask, “Well, where is the Psalm?” Good question. You see, in the early Church, they weren’t concerned with how long the service was. They weren’t anxious to get home to watch a ball game or pile in the car to drive to grandma’s or run out to the Old Country Buffet for lunch; if they were ever concerned with getting out of the Liturgy quickly it would have been because they were running away from people who wanted to cut their heads off or feed them to lions.  In the early days of the Liturgy in Constantinople, when the service could easily run for three or four hours, a good hour and a half of that would be spent in signing Psalms. Of course, the Church wasn’t competing with TV, sports or the short attention span of an impatient congregation; present company excepted, of course. But as the years progressed, it seemed desirable to shorten the service somewhat; and what were sacrificed were the Psalms: first, by cutting them short to one or two verses—as we saw with the antiphons—and, in some cases, eliminating them altogether, leaving only the refrains composed by the Fathers of the Church, leaving what we know today as the Troparia and Kontakia. The same would be true for the Stichera we sing at Vespers, which have the same history. In the early days of the Liturgy in Constantinople, when the service could easily run for three or four hours, a good hour and a half of that would be spent in signing Psalms. Of course, the Church wasn’t competing with TV, sports or the short attention span of an impatient congregation; present company excepted, of course. But as the years progressed, it seemed desirable to shorten the service somewhat; and what were sacrificed were the Psalms: first, by cutting them short to one or two verses—as we saw with the antiphons—and, in some cases, eliminating them altogether, leaving only the refrains composed by the Fathers of the Church, leaving what we know today as the Troparia and Kontakia. The same would be true for the Stichera we sing at Vespers, which have the same history.

The first Troparia and Kontakia composed seem to be traceable to a saint whose minor feast we celebrate every year: St. Ephraem the Syrian, who’s work first appears in the second century; but many believe he may have been a personal disciple of St. John the Evangelist. St. Ephraem, in addition to being a bishop and a very learned theologian, was also an extremely gifted musician, and he composed his hymns as a clever way to inoculate his people from the many heretical ideas that were already floating around the early Church. His early Troparia and Kontakia, composed in the Syriac language, set a high standard for all the other hymnographers who came after him; and there were many. His hymns touched on the major truths of the faith: death, judgment, the resurrection, and so forth. The Greek speaking hymnographers, in Contantinople and elsewhere, who came after him, used him as their model in both style and content. Among them were Fathers of the Church such as Methodius of Olympus, Synesius of Ptolmais, Gregory Nazianzen (Patriarch of Constantinople), Sophronius (Patriach of Jerusalem), John Damascene, and the most prolific of them all, St. Romanos the Hymnographer, whose image graces the cealing of this very church in which we worship, and whose hymns continue to be used in our Church today. In fact, most of the texts in our services for Christmas are exclusively his. Last year Pope Benedict devoted one of his General Audience addresses to him.

Of course, most of the music that these men composed to go along with their beautiful words has long since passed out of use. Later on, the various Eastern Churches would compose their own music to fit these ancient texts—music which reflected their own unique cultures. Probably the most complicated musical system in use by any Eastern Church today is the one used by our own Ruthenian Church, with our various tones and so forth. Russian and Greek and Arabic Christians.... When they look at our music it makes their heads spin. But that doesn’t seem to bother most of our people, especially since we’ve been singing these same melodies, in Slavonic and later in English, for over 300 years. In fact, go to any church in our Metropolia and you’ll find the people singing.

Whether we are adept at singing the Troparia and Kontakia or not, we need to resist the temptation to simply let them roll by without paying attention to them. We need to somehow focus on their words. Our ancestors did not sing them just for the sake of singing songs; it wasn’t like it is today in the Western Church, where you open up the hymnal and just choose one whenever the Missal calls for a hymn. Our Liturgy doesn't allow us to choose these hymns for ourselves; they are specified for each Sunday and Holy Day of the year. These hymns contain, over the course of the year, an entire compendium of the Christian Faith in poetic form. Our ancestors knew their religion inside and out, and were able to preserve it in the face of virulent persecution, not because they had read books or attended classes and seminars, but because they sang the truths of their faith every single Sunday over the course of the year. The Communists could not burn it out of them. They had been singing the theological truths of the Christian religion since childhood.

That’s why it doesn’t matter whether we sing them well; what matters is that we sing them. When I celebrate the Liturgy on a weekday and have no cantor to help me and no congregation present, I still sing the Troparia and Kontakia. I don’t always sing them well, but I still sing them. When I scold you for not singing, it’s not because I’m some kind of maniacal music lover; it’s because it’s the singing of these texts which enables us—as it did for our ancestors—to preserve our faith and pass it on to our children. That’s why the page numbers for them are up on the hymn board: they’re not supposed to be sung by the cantor doing a solo with you sitting there listening; you’re supposed to sing them. The cantor’s just there to help you.

In the Western Church, in medieval times, the architects of the great Gothic cathedrals like Notre Dame and Chartre, told the story of Christianity in relief carved in stone and in their beautiful stained glass windows, so that people could learn their religion simply by being present in church. But a thousand years before Notre Dame was ever conceived, the hymnographers of the Eastern Churches were doing the same thing in song. We need to sing these hymns because that’s how we preserve our faith and how our church survives.

Father Michael Venditti

|