The Divine Liturgy, Part Three: the Proskomedia and the Communion of the Saints.Rom. 5:1-10; Matt. 6:22-34. The Third Sunday after Pentecost, known as the Third Sunday of St. Matthew.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

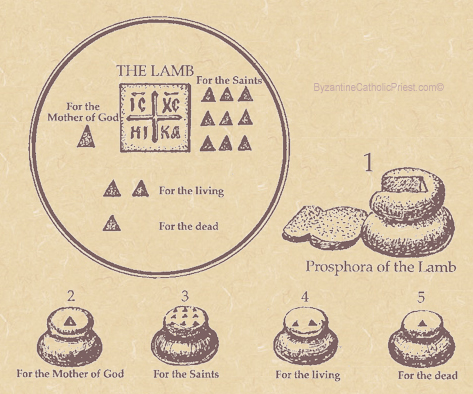

1:44 PM 7/3/2011 — As I indicated to you last week, today we’re going to continue our discussion of the Divine Liturgy with that part of the service known as the Proskomedia. Some of the history behind this part of the Divine Liturgy I’ve put in this week’s bulletin; so, I’m not going to repeat that for you here. Rather, I’d like to focus here on the actual Proskomedia itself, which I have delayed doing today, so that I can do it for you here on the tetrapod while I explain it. There are, however, a couple of illustrations in the bulletin which you may find helpful to keep in front of you as we go through the ritual.*

You’ll recall, of course, that our guide through much of these instructions has been the very holy and informative St. Germanus, Patriarch of Constantinople in the 8th Century. I mentioned to you a couple of weeks ago how the Liturgy he describes to us is pretty much the same as that which we do today; but there are a few differences. One of the must striking, I suppose, is that in his description of the Liturgy there is no such thing as an icon screen, so there are no doors to open and close.  The icon screen or inconostas as it’s called, didn’t develop until the 11th Century as a reaction to the iconoclastic heresy, which we discussed many years ago in a homily about icons. But another difference between the Liturgy he describes and the one we celebrate today, and which is discussed briefly in your bulletin, is the location of the Proskomedia in relation to the overall service. St. Germanus describes the Proskomedia as taking place in a completely different building. It was there that the people attending the Liturgy would bring their own gifts of bread and wine, along with other items of food and gifts which they wished distributed to the poor. The priest would receive from them the gifts of bread and wine, prepare them in the same manner as we will do in a moment, then process with them to the church. His entrance into the church with the gifts of bread and wine is what corresponds in our current Liturgy to the Great Entrance. The icon screen or inconostas as it’s called, didn’t develop until the 11th Century as a reaction to the iconoclastic heresy, which we discussed many years ago in a homily about icons. But another difference between the Liturgy he describes and the one we celebrate today, and which is discussed briefly in your bulletin, is the location of the Proskomedia in relation to the overall service. St. Germanus describes the Proskomedia as taking place in a completely different building. It was there that the people attending the Liturgy would bring their own gifts of bread and wine, along with other items of food and gifts which they wished distributed to the poor. The priest would receive from them the gifts of bread and wine, prepare them in the same manner as we will do in a moment, then process with them to the church. His entrance into the church with the gifts of bread and wine is what corresponds in our current Liturgy to the Great Entrance.

Now, in a large church like Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, you would typically have the Liturgy celebrated by the patriarch assisted by a number of priests and deacons. One of those priests would begin the service in church the same way we do today, while, at the same time, the bishop would be performing the Proskomedia and preparing the bread and wine in this other building. And then, when the time came for the Great Entrance, the bishop would process into the church from the back, bringing the gifts of bread and wine with him. This was also the reason why the homily or sermon was not preached until the end of the service: because, at the time the Gospel is sung, the bishop, who would ordinarily preach, would not yet be in the church.

Now, you can see right away how this would be impractical in a parish setting where there is only one priest to do the whole service; so, at some point after the 8th Century, the Proskomedia was moved into the church itself; and the Great Entrance into the church of the bishop with the gifts became what we know as the Great Entrance today, with the priest processing with the gifts out of the Northern door, around the front of the sanctuary, and into the sanctuary again through the Royal Doors. The prayer that the priest sings while doing this, praying for the Holy Father and the government and the armed forces and the people, is most likely an abbreviation of a hymn that was sung during the entrance of the bishop.

Now, during the Proskomedia, the prayers recited by the priest refer to certain events in the life of our Lord, and mention certain saints; and I wish to explain them to you as we go along.

As the priest cuts the prosphora into the desired shape, he prays in words which recall the passion of our Lord, using the words of Isaiah the Prophet: “He was led as a sheep to the slaughter. And as a spotless lamb is silent before his shearers, so he did not open his mouth. In his humiliation his judgement was taken away. Who shall indeed describe his generation?” These words were used by Isaiah in the Old Testament to describe how the messiah would sacrifce his life for his sheep without complaint. With these words, the priest cuts the round prosphora into a square shape which is called the Oknetz, which is Greek for Lamb. The Lamb of God. The Lamb is then scored or carved by the priest with the sign of the cross, then placed on the diskos.

Then, he takes his lance or knife and stabs the Lamb in the right side, recalling that event in which our Lord, hanging on the cross, was pierced on the right side by one of the soldiers presiding over his crucifixion. Because of the reference to the Gospel of St. John, describing blood and water flowing from our Lords side when he was pierced, it’s at this point that the priest poors wine and a little bit of water into the chalice.

The next part of the Proskomedia deals with the commemorations. Here the priest takes smaller particles of the prosphora and places them on the diskos, with each one representing the presence of a particular saint, beginning with the Mother of God. In your bulletin, you can see the general outline of how these particles are placed, the Mother of God, of course, always being at our Lord’s right hand. The nine particles placed to Christ’s left, which is your right in the illustration, represent various saints, some of whom you may know, and others not.

The first is in honor of the angels; the second, John the Baptist; the third, the Holy Apostles Peter & Paul and all the apostles.

The fourth particle represents a number of saints important to both the Eastern Churches in general and to the Slavonic Churches in particular: Basil the Great, whose Liturgy we celebrate during Lent; Gregory the Theologian, whose presanctified Liturgy we celebrate during Lent as well; John Chrysostom, whose Liturgy we are celebrating now; Nicholas of Myra, the patron saint of all Greek Catholics; Cyril and Methodius, the two brothers who brought the Gospel and the Eastern Tradition to Eastern Europe; the Holy Priest and Martyr Josaphat, who converted many Orthodox Christians to Catholicism in the 15th century.

The fifth particle commemorates the Holy martyrs of the Church, and mentions some by name: the first martyr, the archdeacon Stephen, whose death is described in the Acts of the Apostles; St. Demetrius, who was martyred in the year 306 in Thessalonica; the Great Martyr George, the Cappadocian soldier martyred by the Emperor Diocletian when he converted to Christianity; Theodore of Tyre, a Roman soldier, who also died because he became a Christian; and all the other martyrs over the centuries are commemorated and made present at the Liturgy through this particle. The fifth particle commemorates the Holy martyrs of the Church, and mentions some by name: the first martyr, the archdeacon Stephen, whose death is described in the Acts of the Apostles; St. Demetrius, who was martyred in the year 306 in Thessalonica; the Great Martyr George, the Cappadocian soldier martyred by the Emperor Diocletian when he converted to Christianity; Theodore of Tyre, a Roman soldier, who also died because he became a Christian; and all the other martyrs over the centuries are commemorated and made present at the Liturgy through this particle.

The sixth particle commemorates those who gave themselves completely to God in the desert and in monastic life, and some are mentioned by name: St. Anthony, the most famous of the Desert Fathers, born in Upper Egypt; he left his home and became a hermit in the desert to live a perfect Christian life, living on bread and water for most of his life, and becoming famous for the miracles he performed. St. Euthymius, the founder of monasticism in Armenia, and who was known for his extreem penance. St Sabbas, a Palestinian Christian and the founder of monasticism in the Middle East. St. Onuphrius, a Greek, who is recognized as the Father of Greek Monasticism. And added to these are all the holy men and women over the centuries who forsook the world to follow Christ in perfect poverty and renunciation of the world.

The seventh particle placed on the diskos makes present to us a group of saints called by the unfamilar word “unmercenaries.” The word literally means “without silver,” and refers to saints who spent their lives in the service of others without seeking any reward; and it just so happens that all of them we commemorate here happen to have been physicians. The first to be mentioned are two Arab brothers from Syria, Cosmas and Damien. They were doctors, who gave away their services for free as their observance of Christian charity. Although very noble, it’s not a good way to make yourself popular in Arabia, where the practice of medicine was very advanced in the ancient world, and was a source of income for educated Arabs; so they ended up tortured and beheaded for their generosity. The next two are very similar: Cyrus and John were Christian medicos in Alexandria. Cyruys was actually the doctor; John was a soldier from Mesopotemia who helped him. When they wore out their welcome in Alexandria giving away free medical care, they fled to Arabia—God only knows why—where they, too, were tortured and had their heads cut off. The remaining two unmercenaries were thrown together by fate: Panteleimon was the personal physician of the Emperor Galerius Maximianus, even though he was a Christian. He deserted the faith for a while, tempted by the high lifestyle of the Imperial court; but a holy priest, St. Hermolaus, brought him back to the faith and away from the court. They were both tortured and beheaded during the reign of Diocletian.

The eighth particle commemorates the parents of the Mother of God, Joachim and Ann; and the ninth, the patron saint of the church in which the Liturgy is being celebrated.

If you look at your bulletin again, the nine particles to the right of the Lamb are the ones we’ve been talking about. Under these, along the bottom, you’ll see the particles for the living and dead. Among the living, of course, are included particles for our Holy Father, Pope Benedict, our Metropolitan, our Bishop. And if the Liturgy has been requested for someone living, that person is commemorated by name with his or her own particle. The row of particles underneath that is for the dead. If the Liturgy has been requested for someone deceased, a particle for that person is placed, as well as any other deceased persons the priest wishes to remember. A final particle is placed for the priest himself, and for the forgiveness of his sins.

Once the particles are placed on the diskos, the priest blesses the incense, then he places the various veils over the gifts, incenses them, then incenses the Holy Table as the public portion of the Liturgy begins.

Commemorating all these different saints in this way reminds us that, when we celebrate the Divine Liturgy, we are actually joining in the heavenly liturgy of the Communion of the Saints, who are present with us whenever we are gathered in this way.

Father Michael Venditti

* The article referred to may be viewed in the bulletin for this particular Sunday, which is available on the web site of Father Michael's church, St. Michael, a link to which is provided on the front page of this site. The bulletin will be available until Saturday, July 9th, when it will be replaced by next Sunday's bulletin. To save storage space, St. Michael's does not archive past bulletins on its web site. Since this homily does not pretend to give a complete explanation of the Proskomedia, it is highly recommended that the bulletin article be consulted while it is available.

|