Is It Time to Dust Off the Bound Powers Theory?

One potential legacy of Pope Benedict's Papacy.

FatherVenditti.com

| 3:47 PM 7/26/2012 — Twice a year, on Labor Day and Memorial Day, I attend a picnic provided by one of my former seminary professors in upstate New York where he is now a pastor, and the discussions are quite lively. The atmosphere is similar to those annual theological seminars that Pope Benedict has every summer for his former students, though I'm guessing a little less formal. Not long ago, we were rejoicing over one of our friends being appointed bishop of a diocese, and the discussion drifted to who would be attending his ordination, at which point I interjected the question of whether it was, in fact, an ordination or a consecration. My former professor responded, "Ah, Michael has always argued for the Bound Powers Theory," and asked whether any of the younger priests present had ever heard of it. None of them had. He went on to add that, in spite of the language used in Vatican II about this subject, nothing in the Council specifically prevents someone from still believing in the ancient theory. It was that episode that got me thinking about the following.

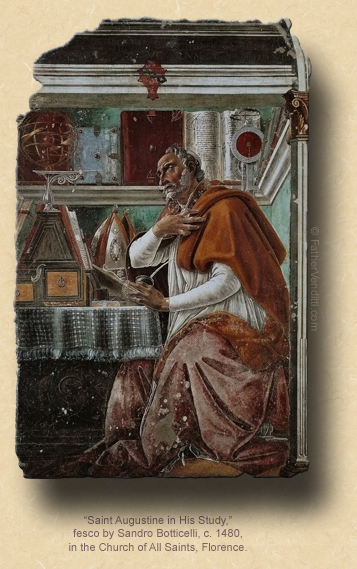

Popes have routinely used the weekly General Audience to focus on some kind of thematic series. John Paul II, having been pope some twenty years, ran through several themes: the Epistles of St. Paul, the theology of the body, etc. Pope Benedict’s first “flight” of General Audience themes, delivered back in 2008, was a series on the Fathers of the Church. Typically, he chose one Father per week, with a few of the more important ones receiving two weeks of attention; but for his theological patron, Augustine of Hippo (that’s pronounced “aw-GUS-tin”, not “AW-gus-teen”, by the way), he devoted six whole meditations. A friend of mine and I decided to reproduce them in our respective parish bulletins week by week. Whether anyone read them, your guess is as good as mine; but, they were there in any case.

I was trained in a Roman Catholic seminary where Thomas Aquinas was the soup of the day; so, when Cardinal Ratzinger was elected Pope, I suffered just a mild case of perturbation, along with the rest of the dwindling number of unreconstructed Thomists around the Church. After all, we had suffered nervously in silence for twenty years with the specter of John Paul II’s modified phenomenology hanging over the theology of the Church like a wrecking ball held by a thread, waiting for just that one little, teensy-weensy, unintelligible Husserlite vagary about perception to be uttered in a careless moment, sending the whole thing crashing down to destroy the settled order of nature.

We Thomists, understand, are an odd lot to the modern mind. I remember, as a seminarian in New York, visiting one of my professors in his parish in Manhattan—he was a Dominican, like Thomas—when he told me the story of the Franciscan priest who had filled in for him when he was out of town:  the Friar Minor complained he couldn’t sleep, saying that he “could sense the realism closing in around him.” Philosophically, a Thomist is an Aristotelian, and his approach to the world around him is decidedly “WYSIWYG” (What You See Is What You Get). Things are what they are all on their own; they are not changed or altered by what you think of them or how you perceive them; and, if you perceive them differently than what they are in themselves, then you either need therapy or glasses. the Friar Minor complained he couldn’t sleep, saying that he “could sense the realism closing in around him.” Philosophically, a Thomist is an Aristotelian, and his approach to the world around him is decidedly “WYSIWYG” (What You See Is What You Get). Things are what they are all on their own; they are not changed or altered by what you think of them or how you perceive them; and, if you perceive them differently than what they are in themselves, then you either need therapy or glasses.

But it isn’t Aristotle’s philosophy which binds us Thomists together in our shrinking fraternity; it’s Thomas' theology, particularly his sacramental theology, which draws a lot from his philosophy—and it’s a lot different from Augustine’s; and Pope Benedict has already begun to chip away at it. Case in point: the case of the episcopal consecrations of the excommunicated Emmanuel Milingo, former archbishop of Lusaka, Zambia, who married a Korean woman in a mass wedding conducted by the Rev. Moon, and who has started his own schismatic “Church” to champion the cause of married Roman Catholic priests. Not too long ago, Milingo consecrated (or ordained, but we’ll get to that later) a few “bishops” for his “Church.” The Holy See immediately responded that the consecrations (or ordinations) were invalid. “Well, that’s a mistake,” said the secret, underground newsletter for unreconstructed Thomists. Illicit they certainly are, but not invalid. Milingo, nutty as he is, is still a validly ordained priest and bishop even if excommunicated, and his sacramental actions are still valid in spite of his unworthiness to perform them. “Not so,” quipped the Holy See, having located the address of the basement where our newsletter is published. “His actions are extra ecclesia (outside the Church), and are therefore invalid.” Kaboom!!! And with that, the unreconstructed Thomists went into hiding. I may be the first to raise my head out of my hole and scream, in my best Nancy Kerrigan voice, “Why? Why?”

You see, on the planet Thomas, so long as you have (1) a validly ordained minister, (2) the correct formula, (3) the proper matter as instituted by Christ, and (4) the deliberate intention to perform the act intended by the Church in this action, your sacrament is valid. It may be illicit (illegal) for a variety of reasons, and its practical effects may be suppressed by the authority of the Church antecedently; but the sacramental effects are there nonetheless. On planet Augustine, you can be four for four as far as the conditions for a valid sacrament are concerned, but if you don’t have the permission of someone whose permission the Church has declared necessary, it’s all just dress-up and make-believe. When Marcel Lafebre consecrated four bishops for his ultraconservative Society of St. Pius X some years ago, it was declared illicit, and it bought him an automatic excommunication since he did it without a papal mandate; but, no one said those bishops were not real bishops; they are recognized as such today. The only difference, I can see, is who was pope in each instance.

Now, to be fair, the Catholic Church has never followed the Thomistic understanding exclusively. In both the sacraments of Confession and Holy Matrimony it has always been understood that proper jurisdiction is necessary for the validity of the sacrament in question. For example, if a priest is filling in for another in a parish not his own, and has no direct permission from either the bishop or the pastor to perform a wedding there, any weddings he may perform would be invalid, and those couples would not, in fact, be married. But to have the previous understanding thrown out in this cavalier way—well, it’s like taking your girl to the door after your fifth date which you think went great, and being told, “Why can’t we just be friends?”

Before continuing, I should like to mention that I do not, in fact, disagree with the Augustinian understanding of things; nor do I actually worry about Pope Benedict’s theology, assuming that one could actually be that conceited. But, I am an unreconstructed Thomist, and therefore like to ask questions. Thomas’ whole philosophical and theological method was based on the asking of questions, the giving of answers, the objecting to those answers (with relevant examples), and the answering of the objections (with even more relevant examples). Thomas used to do it all by himself; that’s how he wrote his books. So, to an unreconstructed Thomist, asking a question does not imply disagreement; it’s just how our brains work. To a subjectivist like, say, a Kantian or a Sartist or a follower of Husserl or Hegal or some other kind of epistemologically confused individual, asking a question always implies disagreement, if not open hostility.

As a proof of my orthodoxy and devotion to the Holy Father (which, by the way, has never been questioned on land or sea), allow me to offer the following. It concerns a different—but related—question to which I previously alluded, and which may, in fact, help to clarify for myself the previous question (stop and think before you answer):

Is the making of a bishop a sacrament?

Don’t answer. Just think. Are you thinking? Good. I will bet you dinner at Bravo (a restaurant that St. Thomas would have loved had it existed in the early middle ages) that your snap answer was, “Yes. It’s a participation in the Sacrament of Holy Orders. Three degrees: bishop, priest and deacon.” Now, grab hold of your calimari, because I think you’re wrong.

I’ll bet you that last slice of brucietto that you’re thinking of Vatican II, aren’t you? Go ahead, admit it. All over the place Vatican II talks about the “ordination” of a bishop. Here’s where I swirl a mouthful of capers and let them roll down my throat with just enough airflow to grunt out, “But Trent called it a consecration, not an ordination; and one Ecumenical Council can’t cancel out a point of dogma defined by another, or else the Holy Spirit is suffering serious emotional problems.” This is where you pitch forward in a sudden spasm and spit a mouth-full of Chianti all over the table. Not to worry. Over espresso and a canoli I will soothe your nerves with a little history (a shot of Compari wouldn’t hurt, either).

Both councils, Trent and Vatican II, debated at length the question of whether the making of a bishop was a participation in the Sacrament of Holy Orders. Both councils taught something particular about it; but, the fathers of neither council had the onions (or should we say stugots?) to actually define anything about it. When speaking of the making of a bishop, Trent refers to it as a “consecration”; when speaking of the same thing, Vatican II uses the word “ordination”; but at no point does either council actually decree anything about it. Look it up. I kid you not.

Let’s apply St. Thomas’ question and answer approach to the problem. To “consecrate” a bishop means exactly what it means to consecrate anything else: you bless him and set him aside for special duties, but nothing about him has ontologically changed. To “ordain” a bishop means to give him a higher degree of participation (the highest, in fact) in that sacrament by which men are ordained into the ministerial priesthood of Jesus Christ, thus altering his ontological nature with an indelible mark. The difference is legion for this reason: If a bishop is not ordained but merely consecrated, then the powers of the episcopacy—to ordain, for example—must, therefore, be present in every priest. But we know that a priest who is not a bishop cannot ordain; should he attempt it, the ordination would be invalid and not merely illicit, as the Church has explained on numerous occasions. Therefore, the making of a bishop must be a sacrament of some sort.

But, I object (to myself—it’s just something us Thomists do): for centuries the Church did not have this understanding, as can be demonstrated by this, that, these, those over there, etc., etc. (which I say as I produce handfuls of ancient, crumbling parchments I’ve stolen from the Vatican Library, hidden in my socks). Besides, I’m an Eastern Catholic priest (which I am, by the way); and in our tradition—which is a lot older than yours, nyah nyah—we’ve never referred to the making of a bishop as anything but a consecration. So, there!

What I’m actually arguing with myself about is an old theory, not taught in the seminary anymore, but which old timers like myself will recognize as “The Bound Powers Theory,” which states, basically, this: Ordination to the Holy Priesthood is, in fact, the reception of the fullness of the Sacrament of Holy Orders; but certain powers bestowed in that ordination are “held bound” by the manifest authority of the Church acting in the name of Christ, in such wise that any attempt to exercise those powers extra ecclesia (outside the manifest authority of the Church) would be invalid, not just illicit. This understanding, of course, was accepted by the whole Church long before the time of St. Thomas, all the way up to the Second Vatican Council, which is why the practice of the Eastern Churches reflects it. Guess where it comes from. Go ahead, guess.

St. Augustine! You win a cookie. That’s right, NASCAR fans. And with his pit boss, Benedict XVI, keeping the tires inflated after all these centuries, Augustine is making quite a comeback.

What consequences Benedict’s influence will have on the sacramental theology of the Church, only time will tell. A lot, I suppose, will be determined by how long he lives. If he lives long enough, the changes could be very dramatic indeed; for example, if the making of a bishop is just a consecration via the Bound Powers Theory, then the “unmaking” of a bishop is just as easy. And we don't mean just suspending his faculties, either. That thought should cause not a few bad toupees to tremble, don’t ya think?

|