The Divine Liturgy, Part Six: "Wisdom, be attentive!" The Little Entrance and the significance of the Gospel Book.Rom. 12:6-14; Matt. 9:1-8. The Sixth Sunday after Pentecost, known as The Sixth Sunday of Matthew.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

11:30 AM 7/24/2011 — We’ve discussed the beginning of the Divine Liturgy consisting of the prayers of the priest and deacon before the icon screen, as well as the vesting ceremonies. We talked about the Proskomedia in detail, the Great Ektenia or Litany of Peace, and the Antiphons, with a concentration on the Monogenes or Hymn of the Incarnation. What occurs next, of course, is the Little Entrance, when the priest (or deacon, if there is one) processes out of the Northern Door carrying the Book of the Gospels, and walks in again through the Royal doors, placing the Gospels on the Holy Table, where he took them from in the first place. It’s called the Little Entrance to distinguish it from the Great Entrance, when the priest does the same thing carrying the gifts of Bread and Wine from the table of preparation to the Holy Table.

Now, an outside observer who had never seen our Liturgy before—and who has no experience with Christian Liturgy—could very easily ask himself, “What’s going on?” The priest or deacon takes the Gospel from the Altar, walks around in a circle, then puts it back right where he found it. What’s the point? Why not just leave it where it is and save yourself the trip? But you already know the answer, I’m sure: this is a highly symbolic act, which is grounded in a lot of history.

You’ll remember when we were talking about the Proskomedia, and how the bishop would originally perform this ceremony in a separate building, then bring the gifts to the Church in a solemn procession which survives today as the Great Entrance. Well, the little entrance has a similar history, which is not actually connected to the Divine Liturgy. It is first described in the writings of Etheria in the year 390. During her visit to Jerusalem, she describes the entrance of the bishop into the Church of the Resurrection.  Now, in her description, she is attending not a Divine Liturgy, but a celebration of one of the daily offices of prayer similar to those services that we do here on some weekdays during penitential seasons; and what she describes does not involve carrying the Gospel book, since no Gospel would have been read at such a service. As a matter of fact, the prayer that the priest prays silently to himself as he is making this walk today, is the original prayer from the service she is describing, and doesn’t mention the Gospel at all: Now, in her description, she is attending not a Divine Liturgy, but a celebration of one of the daily offices of prayer similar to those services that we do here on some weekdays during penitential seasons; and what she describes does not involve carrying the Gospel book, since no Gospel would have been read at such a service. As a matter of fact, the prayer that the priest prays silently to himself as he is making this walk today, is the original prayer from the service she is describing, and doesn’t mention the Gospel at all:

O Lord, our Master and God, who in heaven established orders and armies of angels and archangels for the service of Your glory, make this our entrance to be an entrance of holy angels, serving together with us, and with us glorifying Your goodness. For to You is due all glory, etc., etc.

There’s no mention of the Gospel there. In fact, the prayer says very plainly, “...make this our entrance...,” not the entrance of the Gospel but of the priests and other ministers. Obviously, this entrance was originally the beginning of some other service. How it came to be connected with the Divine Liturgy and how the Gospel Book got included in it is not all that clear; though, as you can imagine, there are countless theories, which I’m sure you’re not interested in hearing. Our old friend, St. Germanus—who is so fond, as you know, of saying “Who knows and who cares?”—doesn’t say much about it at all, which is probably wise.

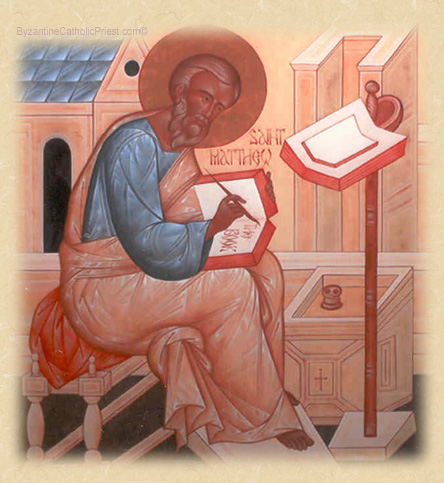

But what is interesting is that, in the Roman Liturgy with which I know many of you are familiar, the Mass begins with a procession with the priest and other ministers walking in from the back of the Church;—very different from the way our Liturgy begins—and it is stipulated that, during this procession, the priest or deacon carries the Book of the Gospels and places it on the altar. Now, you don’t often see that in Roman Churches today, simply because the priest probably just doesn’t want to be bothered. I always did it when I was a Roman priest, but that’s because I always did things by the book, no pun intended. Most likely, the Little Entrance that we know today, with the priest or deacon carrying the Book of the Gospels out of one door and in another, developed as a result of the influence of other Liturgical traditions on the Eastern Liturgy. Some have suggested that it developed in parish churches where the bishop was not present, with the Gospel book representing the bishop who stood in the place of Christ. Whatever its origin may be, in was certainly in place when St. Germanus wrote about it, who tells us that the entrance of the Gospel Book represents the presence and entrance of Christ. And from that point on, the Gospel book itself came to be a profound symbol of Christ himself.

What other reason would we have of adorning the Gospel Book with an elaborately decorated cover, the way we do? When the singing of the Gospel is completed, the Gospel Book stands up on the Altar itself, as if Christ himself is presiding over the Liturgy which is taking place there. Even an outside observer with no contact with Christianity would be immediately aware that this was no ordinary book, especially when the priest raises it over his head and shouts, “Wisdom! Be attentive!” What you may not be aware of is that the word “Wisdom” here does not refer to the simple fact that there is wisdom contained in the words of the book. “Wisdom” is another name for Christ, dating from the earliest days of Christianity. The Church of Holy Wisdom in Constantinople—Hagia Sophia in Greek, built by Justinian, and where St. Germanus and many other patriarchs before and after him celebrated the Divine Liturgy—is really titled the Church of the Holy Savior. For the early Christians, as it is for us, the Gospel is Christ. That’s why, after the signing of the Gospel, the Gospel Book stands up on the Holy Table right there with the Eucharist itself. The Altar is for Christ alone—Christ in the Eucharist as well as Christ in the Gospel. And when we hear these words sung to us by the priest, we are not just hearing stories about Jesus in the way that one might tell a bedtime story to a child; we are hearing the voice of Christ himself. That’s why only the priest can read the Gospel at the Divine Liturgy: because the priest at the Liturgy stands in the place of Christ, so only he can pronounce the words of Christ. That’s why we stand when the Gospel is read: because we are being addressed by our Lord.

Of course, hearing the Gospel is one thing; putting it into practice is another. We all suffer from that hardship. But it can help to motivate us if we keep in mind that, in the Gospel, Christ himself is standing before us and speaking. It is much more difficult to ignore someone when you realize he is standing right there before you.

Father Michael Venditti

|