Don't Be a Closet Protestant.

The Sixteenth Saturday of Ordinary Time; the Memorial of Saint Bridget, Religious;* or, the Memorial of the Blessed Virgin Mary on Saturday.

Lessons from the secondary feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Jeremiah 7: 1-11.

• Psalm 84: 3-6, 8, 11.

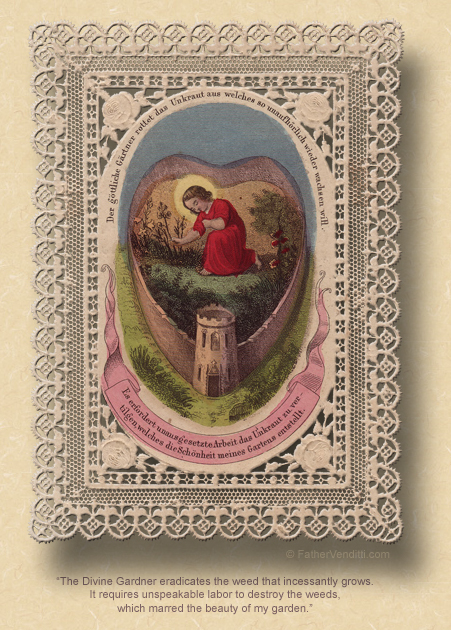

• Matthew 13: 24-30.

|

When a Mass for the memorial is taken, lessons from the feria as above, or any lessons from the common of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

|

The Third Class Feast of Saint Apollinaris, Bishop & Martyr; and, the Commemoration of Saint Liborius, Bishop & Confessor.**

Lessons from the proper, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Peter 5: 1-11.

• Psalm 88: 21-23.

• Luke 22: 24-30.

|

If a Mass for the Commemoration is taken, lessons from the common "Státuit…" for a Confessor Bishop:

• Eccesiasticus 44: 16-27; 45: 3-20.

• [Gradual] Ecclesiasticus 44: 16, 20.

• Matthew 25: 14-23.

|

In the United States:

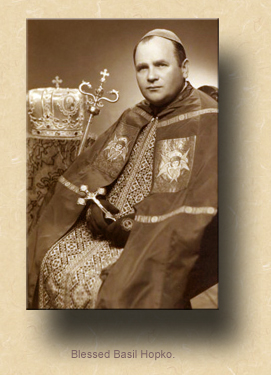

The Ninth Saturday after Pentecost; the Feast of the Holy Martyrs Trophimus, Theophilus & their Companions; the Feast of the Holy Martyrs Apollinaris & Vitalis, Bishops of Ravenna; the Feast of Our Holy Father Basil Hopko, Bishop of Midila; and, the Feast of Our Holy Father Sharbel Makhluf.***

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Romans 15: 30-33.

• Matthew 17: 24—18: 4.

|

Outside the United States:

The Ninth Saturday after Pentecost; and, the Feast of Our Holy Fathers Cyril & Methodius, Apostles to the Slavs.***

First & third lessons from the pentecostarion as above, second & fourth from the menaion as below:

• Hebrews 13: 17-21.

• John 10: 9-16.

|

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:35 AM 7/23/2016 — Today's Gospel lesson presents what I like to call one of our Lord's “idiot” parables. I call them that because, after our Lord tells these parables, He often goes on to explain them to His disciples, leaving us with little to do by way of trying to figure it out. 8:35 AM 7/23/2016 — Today's Gospel lesson presents what I like to call one of our Lord's “idiot” parables. I call them that because, after our Lord tells these parables, He often goes on to explain them to His disciples, leaving us with little to do by way of trying to figure it out.

But in the case of the Parable of the Wheat and the Weeds—or, as the more traditional translations put it, the Wheat and the Tares—knowing the meaning of the parable is only the beginning of the problem for us; because of the society in which we live, it's message is not one we are likely to accept without struggle. That’s because we live in the midst of a Protestant society; and, while none of us here would be willing to admit it, our understanding of salvation and grace is colored by a Protestant ethic that permeates all of society. Notice that the Protestant preachers you see on TV are never dressed shabbily; they're always dressed to the nines, because it is a part of their theological system to believe that good must be rewarded and evil must be punished, and that this must happen now. They make a point of showing off their prosperity because that proves that they are blessed by God. And if you don't believe that you've been infected by this idea, just ask yourself if you've ever thought that you were being treated unfairly by God. Ask yourself if you've ever been angry with God because someone you loved was taken from you. Ask yourself if you've ever been indignant that evil people seem to have everything they want while good people are left to suffer. How many times have you heard—or perhaps even said to yourself—“I've lived a good life; why is God letting this happen to me?”

The Parable of the Wheat and the Tares is so simple that it seems almost incredulous that it would require any explanation at all. The good and the bad live on this earth side by side; they aren't sorted out until the final judgment. And as for rewarding good deeds and punishing evil, that, too, is left for the end of all things; it doesn't happen now. And you can see how difficult a concept this is for us, raised as we are with such a strict sense of justice and reciprocity. When someone famous is accused of a crime, and the trial is aired on television, and the person is acquitted even though we were all convinced of his guilt, we become angry. Why are we angry? Because we feel that justice has not been done. Whenever a part of our country is hit by some disaster—whether it’s a terrorist attack or some sort of natural disaster or any kind of catastrophic event that causes lose of life—what's the first thing everyone wants to know? “Who can we blame? Who should have known? Who can we make accountable?” And we feel that way because evil must be punished. We can't stand the idea of someone not getting their comeuppance.

But what's most disturbing about this attitude that all justice and all recompense must be in the here and now is that it is rooted, I believe, in a lack of faith. We try to go through the motions of believing our Lord: we confess our sins, we grieve for the wrong we've done to others, we offer prayers and sacrifices for the outrages committed against our Lord, our Blessed Mother, our Church; but, when push comes to shove, and some tragedy comes our way, we just can't help ourselves, and find ourselves asking that perennial question of doubt: “I've lived a good life; why is God letting this happen to me?”  The answer, of course, is in the parable; but, we don't want to hear it, and so we block it out of our minds as if our Lord doesn't really mean what He says. On Sundays and solemnities, when we recite the Creed, we'll all say together, “…I look forward to the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come,” and we say it with all sincerity; but, saying it and believing it are two different things, and living it is something different altogether. The answer, of course, is in the parable; but, we don't want to hear it, and so we block it out of our minds as if our Lord doesn't really mean what He says. On Sundays and solemnities, when we recite the Creed, we'll all say together, “…I look forward to the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come,” and we say it with all sincerity; but, saying it and believing it are two different things, and living it is something different altogether.

To live in the midst of this world without being a part of it; to pace out the course of our lives as pilgrims whose journey does not end except in heaven: that is the faith that Jesus challenges us to embrace. There isn't one of us here who hasn't failed to embrace that faith at some point in his or her life. But, thanks be to God, we have a Savior who understands our human condition because He became one. He took our sins upon Himself, and offered Himself as a sacrifice on the altar of the Cross, a sacrifice which we will have reproduced for us upon this altar, and the broken Body of our God will again be offered to us to adore and receive in Holy Communion. That is a great grace, and one that can overcome all our lack of faith, if we will only dispose ourselves to allow it.

* Born in Sweden in 1303, Bridget was the mother of eight children, including the future St. Catherine of Sweden. After her husband's death, she dedicated herself to an ascetical and contemplative life; and, after a brief time as a Franciscan tertiary, founded the Order of the Most Holy Savior (the "Bridgettines"). Along with St. Catherine of Siena, she was instrumental in ending the luxury and dissipation of the Avignon papacy, pressuring the pope to return to Rome. She died in Rome in 1373. She is the patroness of Sweden; and, in 1999 Pope St. John Paul II declared her, along with St. Catherine of Siena and St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (Edith Stein), co-patroness of Europe.

** Tradition holds that Apollinaris was consecrated a bishop by St. Peter, himself, and sent to Ravenna on the Adriatic coast during the reign of Claudius. Renowned as a healer, he was exiled, tortured, imprisoned and finally beaten to death c. AD 79.

Liborius, a Gaul, was Bishop of Le Mans in France and died in AD 395.

*** Basil Hopko (1904-1976) was Auxiliary Bishop of Preŝov for the Ruthenians (Midila was his titular see), and spent fifteen years in prison during the Communist oppression in Slovakia. In the latter part of his life, he suffered intensely from clinical depression, and is a patron for those with the same malady. He was beatified by Pope Saint John Paul II on September 14th, 2003. The Ruthenian Metropolia in Europe observes his feast on May 11th, the day of his consecration as a bishop, observing the Feast of Ss. Cyril & Methodius today; but, since the Ruthenian Church in the United States observes Cyril & Methodius on May 11th, it observes Bl. Basil Hopko today, the day of his death. Lessons and other texts for his feast are still pending.

St. Sharbel (1828-1898), sometimes spelled Charbel, was a holy monk of the Maronite Catholic Church in Lebanon, and was canonized in 1977 by Pope Bl. Paul VI. The Maronite Church is the only Eastern Catholic Church never to have been a "uniate" church, that is, it was always in union with Rome and did not "convert" from Orthodoxy; thus, the Church has no Orthodox counterpart. At one time, it was the dominant religion of Lebanon. It celebrates the liturgy according to the Antiochene Rite, and it's liturgical language is Aramaic, the Hebrew dialect spoken by our Lord. The Church has a significant presence in the United States.

|