The Patron Saint of the Frustrated.

The Memorial of Saint Bonaventure, Bishop & Doctor of the Church.

Lessons from the primary feria (the Fifteenth Monday of Ordinary Time), according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Exodus 1: 8-14, 22.

• Psalm 124: 1-8.

• Matthew 10: 34—11: 1.

|

…or, from the proper:

• Ephesians 3: 14-19

• Psalm 119: 9-14.

• Matthew 23: 8-12.

…or, any lessons from the common of Pastors for a Bishop, or the common of Doctors of the Church.

|

The Third Class Feast of Saint Henry, Emperor & Confessor.*

Lessons from the common "Os justi…" of a Confessor not a Bishop, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ecclesiasticus 31: 8-11.

• Psalm 91: 13-14, 3.

• Luke 12: 35-40.

FatherVenditti.com

|

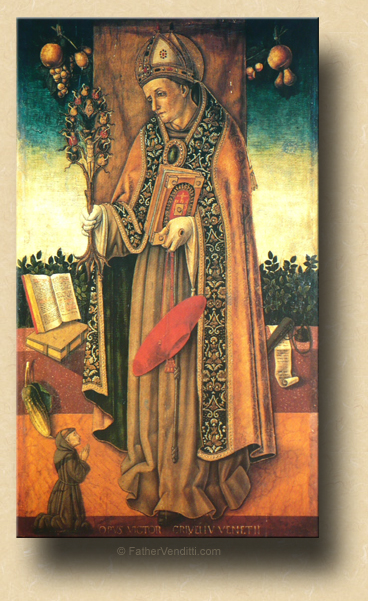

2:35 PM 7/15/2019 — Today we observe the memorial of the Seraphic Doctor, the title that Pope Sixtus V gave him after his predecessor, Sixtus IV, canonized him. We don't typically associate the Franciscan Order with men of great learning, but Bonaventure may have been the most brilliant man of the Middle Ages next to Saint Thomas Aquinas, of whom he was a contemporary. They taught together, in fact, at the University of Paris in spite of the fact that they were both Italians. 2:35 PM 7/15/2019 — Today we observe the memorial of the Seraphic Doctor, the title that Pope Sixtus V gave him after his predecessor, Sixtus IV, canonized him. We don't typically associate the Franciscan Order with men of great learning, but Bonaventure may have been the most brilliant man of the Middle Ages next to Saint Thomas Aquinas, of whom he was a contemporary. They taught together, in fact, at the University of Paris in spite of the fact that they were both Italians.

He was born in Tuscany, entered the Franciscans at an early age, was known for not only his learning but also for his profound devotion to the Passion of Our Lord. At the age of thirty-five he was elected Minister General of the Franciscan Order, and became known for his diplomacy and prudence. Pope Gregory X pulled him out of his order and made him a Cardinal, sending him to the town of Albano as its bishop, and it was in that capacity that he went to Lyons to participate in the Council there, but died while there at the age of forty-three.

It all sounds very serene, but there are aspects of his life that are not generally known, and which caused some consternation when Sixtus IV canonized him. He was elected Minister General of the Franciscans in 1257, at a time when the Franciscans were just beginning to become fragmented. Now days, we're familiar with all the various branches of the Franciscan Order: the Friars Minor, the Capuchins, the Conventuals, not to mention the plethora of more modern groups that have sprouted off from the Franciscan family or have simply attached his name to themselves; but, at the time, the Franciscans were still one group, but were just beginning to have all these internal dissensions within themselves. Bonaventure dealt with all this in a very heavy-handed way. The chief disagreement within the Order was between one group who wanted to embrace a very strict and severe interpretation of Franciscan poverty, and those who thought that the Order needed to change with the times in order to survive, and both groups claimed  support for their respective positions by citing their own versions of the life of Saint Francis, the actual facts of which are sketchy at best. support for their respective positions by citing their own versions of the life of Saint Francis, the actual facts of which are sketchy at best.

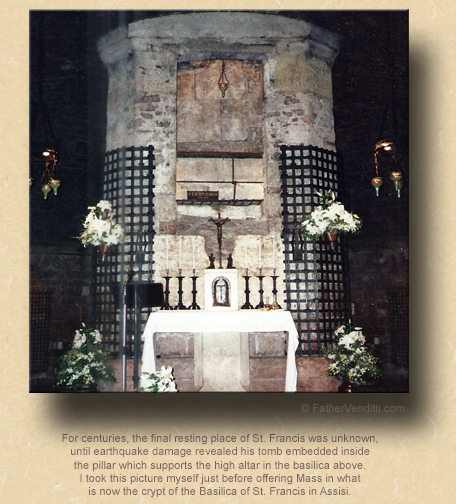

In 1260, Bonaventure composed his own version of the life of Saint Francis, and commanded that all other biographies of Francis of Assisi be destroyed, and its from that work that most of what we believe about Saint Francis is known. Where he got most of his information about the life of Saint Francis no one knows, but those who felt he was not on their side accused him of simply making most of it up to support his own idea of what he wanted the Franciscan Order to become. In any case, he convened a General Chapter of the Order in 1263, and imposed a rather ridged uniformity among the Franciscans; and, while Bonaventure's reforms held the Order together for a while, ultimately it did disintegrate, which is why we have so many different Franciscan communities today.

When you set yourself to study the lives of the saints—not the homogenized, pious versions of their lives, but the real lives of the saints with all the nastiness included—you realize what a tremendous capacity these people had for maintaining their spiritual equilibrium amid all kinds of chaos and unpleasantness. The Church is of Divine origin, but Christ entrusted her to men, and those men are beset by a fallen nature, which means that the Church is not always going to be governed the way it should be. What distinguishes the saints from the rest of us is their ability to—simply put—not allow themselves to be bothered by it. It doesn't mean that a saint is complacent; quite the contrary, as evidenced by Saint Bonaventure's work to reform the Franciscans the best way he knew how. But at no time during all the controversies that he was forced to endure as Minister General of the Order did Bonaventure ever loose his holiness; and, we have to presume that his profound devotion to the Passion of Our Lord allowed him to see, in all he had to put up with, a participation in the Cross of Christ.

If we would be saints, which all of us are called to be, we should know instinctively how to put it all in perspective. And when we kneel here before the Altar, and cast our eyes upon the Body of Christ, we know that, no matter what may be going on in our lives, Christ is always there, and he is always the same.

As for today’s alarming Gospel lesson:

In all my years of hearing confessions, those I find the most edifying are those in which someone confesses that they have failed to put God first in their lives. I can only assume that these confessions are motivated by some spiritual reading they are doing, or some sort of direction or preaching by someone better than me. Of course, it’s the sort of thing you hear only from someone who confesses frequently—once a week or once every couple of weeks—and it reflects a high degree of commitment to spiritual perfection. For those not so advanced in the interior life, Our Lord’s instruction to His Apostles in today’s Gospel lesson is confusing: Isn’t the family the cell of the Church? Aren’t my duties to my family part of my obligation to Christ and His Church? The answer, of course, is “Yes,” but eschews the more mystical element being expounded upon by Our Lord, which is easily misunderstood by those whose knowledge of—and practice of—the interior life is very elementary. In all my years of hearing confessions, those I find the most edifying are those in which someone confesses that they have failed to put God first in their lives. I can only assume that these confessions are motivated by some spiritual reading they are doing, or some sort of direction or preaching by someone better than me. Of course, it’s the sort of thing you hear only from someone who confesses frequently—once a week or once every couple of weeks—and it reflects a high degree of commitment to spiritual perfection. For those not so advanced in the interior life, Our Lord’s instruction to His Apostles in today’s Gospel lesson is confusing: Isn’t the family the cell of the Church? Aren’t my duties to my family part of my obligation to Christ and His Church? The answer, of course, is “Yes,” but eschews the more mystical element being expounded upon by Our Lord, which is easily misunderstood by those whose knowledge of—and practice of—the interior life is very elementary.

Our only purpose for being on this earth is to work out our salvation. That’s the secret to processing what Our Lord tells us today. When He says that we mustn’t love our families more than Him, what He means is that we should recognize that life on this earth is nothing more than a waiting room. Life in this world is a drop of water in the ocean compared to eternity, and it’s eternity that is our true home. He’s not suggesting that we should estrange ourselves from our families and give ourselves over to divine mystical union with Him to the exclusion of everything else. He’s only reminding us that this world and it’s concerns—personal, familial, ecclesial, whatever—are mostly just a distraction from what really matters: keeping ourselves right with God. And we do that by confessing our sins frequently, drawing strength from the Grace of the sacraments,—particularly the Most Blessed Eucharist—and not allowing ourselves to be distracted by popular or social concerns. Our one purpose for being on this earth is to work out our salvation. Everything else is just window-dressing.

* Henry, Duke of Bavaria and Emperor of Germany, used his power to extend the kingdom of God. By mutual agreement, he and his wife preserved their virginity in marriage. He died in 1024.

|