9:10 AM 7/12/2015 —

In him it was our lot to be called, singled out beforehand to suit his purpose (for it is he who is at work everywhere, carrying out the designs of his will) … (Eph. 1: 11 Knox).

That's Msgr. Knox's translation of a verse from today second lesson, taken from the Blessed Apostle Paul's Epistle to the Ephesians. He is writing, of course, about the Holy Priesthood. But he doesn't stop there, because he then goes on to speak of the laity:

… in him you too were called, when you listened to the preaching of the truth, that gospel which is your salvation. In him you too learned to believe, and had the seal set on your faith by the promised gift of the Holy Spirit … (v. 13 Knox).

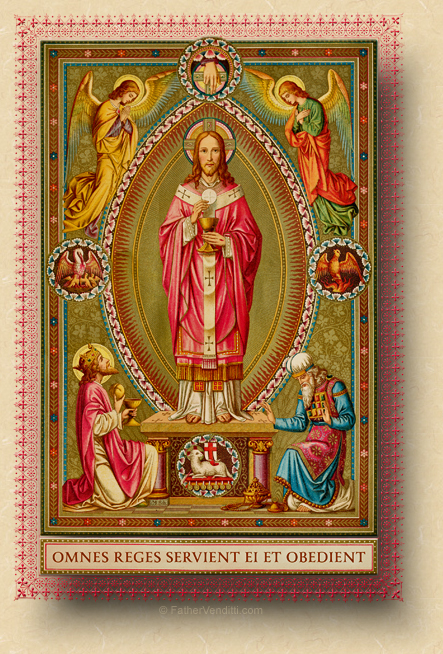

And those of you versed in your Second Vatican Council will no doubt recognize that the Apostle is speaking of the two priesthoods without which the Church of Christ cannot function: the sacramental priesthood—sometimes called the ministerial priesthood—and the priesthood of the faithful or priesthood of the laity. Both are very different, but both spawn from the same sacrifice of our Lord on the Cross, reproduced for us in the sacrifice of the Altar.

And those of you versed in your Second Vatican Council will no doubt recognize that the Apostle is speaking of the two priesthoods without which the Church of Christ cannot function: the sacramental priesthood—sometimes called the ministerial priesthood—and the priesthood of the faithful or priesthood of the laity. Both are very different, but both spawn from the same sacrifice of our Lord on the Cross, reproduced for us in the sacrifice of the Altar.

Of course, when the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council wrote of Saint Paul's concept of the priesthood of the faithful, the subject having been neglected for many centuries, it launched a kind of mania among those who sought to define the Council as some sort of reinvention of Catholicism, which it was not, resulting in an attempt to pretend that priests were no different than anyone else, no better than anyone else, and with no special authority or abilities than any one else. Well, only a small portion of that is true: that a priest may be no better than anyone else we know from our own experience; and, if you think that you've known priests along the way who have fallen short with regard to their purely human qualities—their personalities, their people skills, their personal holiness, their sense of sacrifice and compassion for others—then you should be thankful that you've never had to live with any of them. I've been a priest a long time, and could tell you horror stories that would scandalize you to the edge of loosing your faith. I won't do that, since it would be the antithesis of my job.

I had the privilege a few weeks ago of con-celebrating the funeral Mass of one of the priests of our own diocese; and, the young priest who preached the homily, who had been one of his parochial vicars, mentioned the fact that this priest made a point of never treating his vicars they same way he had been treated by his pastors as a young priest. Not being priests you may not be able to relate to that, but I could, certainly to the point of wishing that I had had a pastor like that in the early days of my priesthood. Very few of us did. When I was ordained, it was still very much in the “old system,” which operated according to a vicious circle: every pastor tormented his vicars, so when the vicars became pastors they only knew one way to treat the priests assigned under them, and no one was interested in breaking the cycle because they all felt they were entitled to take their revenge. I was able to escape the vicious circle only because in every assignment I had as a pastor I was alone; I never had another priest assigned with me.

But all this is what the young people call “TMI” (too much information), and well off the mark of what I would like to offer for your reflection in light of the Blessed Apostles words. Returning to the main point: Paul's concept of the priesthood of the faithful, mentioned by the Council Fathers and being used by others afterwards to blur the line between the clergy and the laity, because the concept was left woefully undefined. We can do our part to correct this problem by going back to the source of the idea in the Epistle itself. The two verses I quoted to you define the concept very clearly: speaking of himself and the other apostles, he says that they were "prædestinati secundum propositum ejus"—“singled out beforehand to suit his purposes”, specifically, to preach the Gospel and to offer sacrifice. Then, he turns his attention to the lay people to whom he's writing: “… in him you too were called, when you listened to the preaching of the truth, that gospel which is your salvation.” In other words, both the ordained priest and the baptized “priest” are called by God to a special vocation, but those vocations are very different. The ordained priest preaches the word of God; the baptized “priest” listens to what is preached and puts it into practice.

The problem arises when the two cross over into each other's territories, and this works both ways. How common is it, in our parishes today, to have battalions of good lay people scampering all over town taking the Blessed Sacrament to homes and hospitals while the priest sits behind his desk pouring over account books and paying bills? To use an overworked cliché, what's wrong with this picture? The flip side we see just as often, even though it may not have occurred to us to recognize it as such: when conferences of bishops release policy statement after policy statement on such seemingly secular topics as immigration reform, economic policy and the environment. They will defend this—and often do—by suggesting that it's their role, as teachers of the faith, to illustrate how the Gospel is to be put into practice, and that's true as far as it goes; but, if one reads the Council Fathers precisely, in light of the words of the Apostle on which the Council Father's teaching is based, it is the job of the bishop to give us the principles that flow from the Gospel of Jesus Christ, and the job of the laity to formulate the policy based on those principles.  If the laity fail to act on his preaching, or if the policy they come up with does not reflect the Gospel closely enough, either because they are disobedient or because he was not clear enough, the bishop must correct them within the realm of his specific office, preaching it again more clearly and more precisely, but not by usurping the laity's function and formulating the policy himself.

If the laity fail to act on his preaching, or if the policy they come up with does not reflect the Gospel closely enough, either because they are disobedient or because he was not clear enough, the bishop must correct them within the realm of his specific office, preaching it again more clearly and more precisely, but not by usurping the laity's function and formulating the policy himself.

Now, all of this may seem very esoteric and academic to you; but, as a priest who's assignment relegates him primarily to a liturgical ministry, I am very sensitive to the proper celebration of the Liturgy of the Church, and am always conscious of the fact that how we worship is important because it expresses what we believe. The liturgy is important not only because it makes present to us the Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of our Lord, God and Savior, Jesus Christ, but it is the primary expression of our faith. In other words, it isn't important simply that the Mass be valid; it's just as important that the Mass be offered precisely according to the rubrics of the Missal, because even what seems to be a trivial and insignificant deviation from a liturgical principle, if left uncorrected, can infect, over time, what we actually believe. Case it point, what we're talking about today: the blurring of the distinction between the ministerial priesthood and the priesthood of the faithful.

For example, how many of us are fond of raising our hands when we pray the “Our Father” at Mass? And how many of us who do that would be shocked—perhaps even offended—to be told that it is quite improper for lay people to do that? The rubrics of the Roman Missal go back over a thousand years. Not just the words, but even the very gestures of the priest have meaning. When the priest at Mass extends his hands, either when offering a prayer or extending a greeting such as “The Lord be with you,” he extends his hands because part of his function, as a priest, is to collect the prayers of the faithful and send them, on their behalf, toward heaven; it is part of what defines him as a priest. You'll notice that when a deacon is present at Mass, and says the words “The Lord be with you,” he does not extend his hands; his hands remain folded in front of him. That's because when he says those words, it is merely a greeting; he is not collecting up the prayers of the faithful to send to heaven. He can't, because he's not a priest.

What we do when we pray privately at home, or even in church during moments of private prayer before the Blessed Sacrament, is our own business; but, when we are at Holy Mass, it's not only the priest and the deacon who have to obey the rubrics of the Missal; the laity, too, must obey them. And the Missal does not authorize the laity to extend their hands at any time during the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. Remember that the liturgy of the Church does not exist simply to provide us with spiritual food for our personal devotion; the liturgy is a public act that we offer to Christ in the name of Christ, and it is the obligation of all of us to do it properly: to cross ourselves when indicated with demeanor and attention; to bow during the mention of the Incarnation when we recite together the Creed; to receive Holy Communion in the proper manner, either on the tongue or, if we choose to receive in the hand, to make sure we're holding our hands in the prescribed fashion. These are not trivial matters.

You may find all this to be hyperbolic—perhaps even extreme—but what does it say to our subconscious when make the sign of the cross haphazardly? Could it not infect us with regard to how willing we are to take up our cross every day and follow the Lord? What does it say when we fail to bow devoutly during the mention of the Incarnation in the Creed? Could it not cause us, over time, to forget that Jesus is true God and true Man? What does it say when we receive Holy Communion without proper reverence, not thinking about what we're doing, holding our hands in some casual and improper way? Does it not reflect, perhaps, that we've forgotten that's it God, Himself, we are receiving? What does it say when we allow ourselves to perform priestly gestures at Mass, like raising our hands during prayer, because we've decided that it's meaningful to us personally or reflects our own personal devotion? Does it not, maybe, cause us to forget that, without some man who was willing to offer his whole life to the Sacrifice of the Altar, we wouldn't have our Lord present among us at all to adore and worship and receive? And does it not cause us, sometimes, to take these men for granted, making it more difficult to forgive and tolerate their human weaknesses and faults?

In him it was our lot to be called, singled out beforehand to suit his purpose (for it is he who is at work everywhere, carrying out the designs of his will); we were to manifest his glory, we who were the first to set our hope in Christ; in him you too were called, when you listened to the preaching of the truth, that gospel which is your salvation. In him you too learned to believe, and had the seal set on your faith by the promised gift of the Holy Spirit … (Eph 1: 11-13 Knox).

The priest and the lay person—both called by God to his or her own vocation; but, neither can fulfill that vocation faithfully unless they both know what they are called to be, and respect what the other is called to be.