The Divine Liturgy, Part Four: The Litany of Peace and the proper disposition for prayer.Rom. 6:18-23; Matt. 8:5-13. The Fourth Sunday after Pentecost, known as the Fourth Sunday of St. Matthew.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

11:10 AM 7/10/2011 — We continue our discussion of the Divine Liturgy. Two weeks ago we looked at the prayers before the icon screen which the priest and deacon recite together, and we emphasized the point that this is actually when the Divine Liturgy begins. So, one could say that the Liturgy can be divided into two parts: that which is done privately, meaning without the participation of the people, and that which is done publicly. Last time we moved on to the rite of preparation, which is called the “Proskomedia.” And we actually did the Proskomedia for you during the homily.

Today we move from the private portion of the Liturgy to the public part; and the first public portion of the Liturgy—that is, the first part which requires the participation of the people—is the Great Ektenia or the Litany of Peace. It is a portion of the Liturgy that exists in some form or another in every Eucharistic Liturgy of Christianity. Even in the Latin Rite, the Mass begins with three petitions to which the people respond “Lord, have mercy.” In the Roman Missal it’s called the “Penitential Rite”; and it’s often presumed, incorrectly, that it’s character is always penitential. In the Eastern Churches, this Litany is, of course, much longer, and is found not only at the beginning of the Divine Liturgy, but also at the beginning of several other services, such as Vespers, Matins, and so forth. We call it the Litany of Peace only because the word, “peace,” figures in the first petition: “In peace, let us pray to the Lord”; but it goes on to include prayers for just about everything you can think of: for the salvation of our souls, for the peace of the world, for the Church, for the Pope, for the Patriarch or Metropolitan, for the bishop and his clergy, for the government, for the city, for good whether and abundant crops, for those traveling and sick and in prison; and just to make sure no one was left out, the last one prays for “deliverance from all affliction, wrath and need.”

Why go to such lengths to make sure everyone is covered? There are two points we can observe about this. One is simply that the Litany reminds us of the tremendous scope of the efficaciousness of the Liturgy itself. The celebration of the Eucharist, whether it’s called the Divine Liturgy or the Mass or whatever a particular Church chooses to call it, whether it’s done according to the words of St. John Chrysostom or St. Basil the Great or the service described by St. Justin the Martyr as the Roman Mass is, it’s still the most powerful prayer there is. There is no prayer more important to Christians or more powerful in it’s ability to help us than that prayer which changes bread and wine into the flesh and blood of Christ. And we pray for all these different people and all these different needs at the beginning of it not only to offer our prayers for them—which is important in itself—but also to remind us of the scope of this prayer we call the Divine Liturgy. There is no aspect of life and no person on earth that cannot be effected by this great miracle of the Holy Eucharist.

But it also reminds of the fact that, in celebrating the Eucharist, we do not do so as an isolated community or parish. We are the body of Christ. The whole Church is united in Christ himself, as Pope Pius XII pointed out in his great encyclical, Mediator Dei. And when we celebrate the Eucharist—and especially when we receive it—we are united not only with Christ as our own personal savior, but also with the whole body of Christ which is the Church. Our celebration of the Divine Liturgy in our little parish church is not simply a service which we pray together as a parish; it is a corporate act which unites us, both as individuals and as a parish, with the whole Church of Jesus Christ.  And so, the Liturgy thrusts the whole Church of Jesus Christ into our faces at the very beginning in the form of the various petitions of this Litany. Note that it draws into our circle of prayer not only those who are celebrating the Eucharist in their own parishes, but also those who are not able to do so, wherever they may be: those who are sick, those who are in prison, those who are traveling. And so, the Liturgy thrusts the whole Church of Jesus Christ into our faces at the very beginning in the form of the various petitions of this Litany. Note that it draws into our circle of prayer not only those who are celebrating the Eucharist in their own parishes, but also those who are not able to do so, wherever they may be: those who are sick, those who are in prison, those who are traveling.

But not only does this litany draw us, by prayer, into a sense of our membership in the Mystical Body of Christ; the individual petitions themselves have meaning for us; and we should look at them; because they illustrate, in a certain way, the kind of attitude we need as we enter into the prayer of the Divine Liturgy, beginning with the very first one which, while being the shortest and simplest of the petitions, is packed with enormous meaning for us. “In peace, let us pray to the Lord.”

In that one simple sentence is summed up what spiritual doctors of the Church have spent volumes talking about, beginning with our Lord himself, who told Martha that her sister, Mary, had chosen the better part, which he called “the one thing necessary.” “In peace, let us pray to the Lord.” One cannot pray, one cannot be in union with Christ, one cannot talk to God at all if one’s soul is in turmoil. The quieting of the passions, the putting away of all earthly troubles and worries, calming ourselves down so that we can talk to God with a clear, clean and calm conscience, is the ideal disposition for prayer. It’s easier said than done; and that’s one of the reasons why the litany begins this way. These are, in fact, the first audible words spoken during the Divine Liturgy, and for a reason.

You can understand this from your own experience, if not currently, then perhaps in the past: You wake up on a Sunday morning, you make your coffee, you wake up the kids, you kick your husband and tell him he needs to go to church. And you come to church with all kinds of things on your mind: everything you went through the past week; everything you’re going to go through in the coming week. Maybe it’s something at work, or maybe you had a fight with your wife. Or maybe your youngest is flunking math. Or maybe you’re going to your in-laws after church and you don’t want to. Or maybe it’s that person in church you don’t like that you dread seeing. Maybe you had tests at the doctor and you don’t have the results yet. It could be anything, but it’s usually something. And there’s someone in the choir loft signing; and the priest is throwing incense around. Then the doors open up and the first thing out of the priest’s or deacon’s mouth is, “In peace, let us pray to the Lord.” And right away the Liturgy is asking us to do something very difficult, and that is to put everything that bothers us out of our minds.

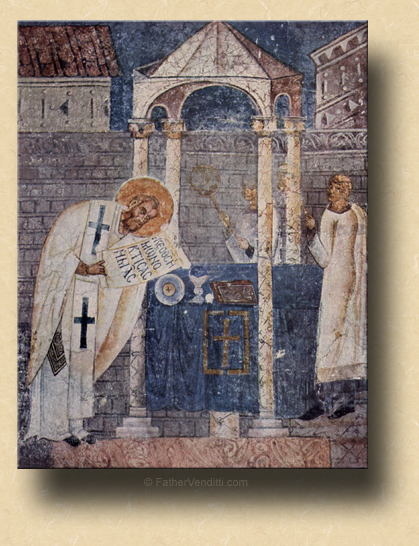

In the year 989, St. Vladamir, prince of what would become the Russian Empire, whose capitol was in Kiev in present day Ukraine, converted to Christianity through the preaching of Ss. Cyril and Methodius. Anxious to learn all he could about his new found faith, he dispatched envoys to Constantinople to report back to him on how Christians lived and worshipped in what he understood to be the center of Christian life at the time. These envoys attended the Divine Liturgy in the church of Hagia Sophia and described their experience in a famous letter to St. Vladamir. And in this letter they say, “We did not know if we were on earth or in heaven; for there is no such splendor to be found anywhere upon earth—describe it we cannot: we know only that it is there that God dwells among men.” When we walk into church, we are leaving the world and it’s worries behind. The icons, the music, the incense, the prayers, the actions of the priest and deacon, everything is designed to take us out of this world and transplant us mystically into the next. The icons do not show Jesus and his Mother and the saints as they appeared on earth; they show them as we imagine they appear in heaven. Our music uses no earthly musical instruments, because the choirs of angels in heaven would not need instruments when they sing to God and neither to we. We use the incense so we don’t even have to smell the world we’ve just left behind. We are being transported, if not in reality than at least mystically in prayer, to another plane of reality where the cares of this world do not exist.

Now, this is in contrast with the very opposite approach that was eventually adopted by the Western Church in the early middle ages. While our Liturgical life and spirituality chose to emphesize the Resurrection and Ascension of Christ, theirs chose to focus on the incarnation and God becoming man in Christ, the idea being to inspire prayer not by raising us up to contemplate heavenly things, but by showing Christ as one of us, intimately involved in our daily lives, suffering what we suffer, overcoming what he asks us to overcome. So the art of the Western Church is not ethereal and otherworldly like ours, but is more realistic: not an icon of Christ in his heavenly glory, but a statue of Christ walking this earth as a man: three-dimensional and lifelike. The music is more modern and changes with the times, using whatever instruments are at hand. In a Roman church, one is not supposed to wonder if one is in heaven or on earth; one is quite obviously meant to feel that he is still here on earth; but one is inspired to believe that Christ is here, too. In the Eucharist itself, it is not so much intended that one should have the sense that one is being raised up to heaven to meet God there, but that God, in his love and mercy, is coming down to meet us where we live, amidst all our troubles and tribulations. The very Mass of the Roman Rite is formed around this medieval concept of God wallowing in the same mud and muck as the rest of us. It’s brevity of length and economy of words is based on the notion that prayer is good, but we don’t have all day. It gets right to the point.

When you look at the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom and the Mass of the Roman Rite side by side, you see this. The Roman Liturgy says in one sentence what the Divine Liturgy takes a whole page to say. Even the very part of the Liturgy that we’re talking about today, the Litany of peace, corresponds to a similar part at the beginning of the Mass that has only three petitions; in fact, in one of the optional forms in the current Roman Missal, there are no petitions: the people and the priest simply say or sing, “Lord, have mercy; Christ, have mercy; Lord, have mercy,” and then there’s an opening prayer said by the priest and the epistle begins and we’re off and running.

We don’t do that in the Eastern Churches, much to the chagrin of some people, and we can’t do that; not because we’re gluttons for punishment or having nothing better to do, but because that’s not our spirituality. While the Mass of the Roman Rite has its roots in the fourth century, it’s current form, and the spirituality surrounding it, developed mostly during the Western Church’s most formative years, which were the early middle ages, just after the two churches of the east and west, Constantinople and Rome, had split apart and went their separate ways. Remember that these were the “Dark Ages” in Western Europe. The Great Plague was in full swing. There were very few great kingdoms in the world and civilization had broken down. Most people were poor and illiterate and hungry. And what kingdoms and governments there were lorded it over their subjects who were mostly surfs and tenant farmers. Everyone, it seemed was suffering; and so the spirituality of the Church in the West, newly separated from its roots in the East, found comfort in a God who came to earth and suffered, too. And the whole growth of the Church in the West, from that point on, was based on this principle, and determined how their spirituality and Liturgy developed.

The Eastern Empire missed the Great Plague and the Dark Ages. After the separation, the Churches in the East felt no need to develop away from the Apostolic traditions that the whole Church had been following up to that point. The emphasis remained, not on the incarnation, but on the Resurrection of Christ and his Ascendency into heaven. And it’s Liturgy held to the tradition of the Apostles, too; a tradition that was intended to inspire us not to look down at the earth and look for God there, but to look up into heaven. And this is the reason that, when compared side by side, the Liturgy and spirituality of the Christian East is as different from that of the West as night differs from day. Not that one is better than another, for each one meets the needs of the people who practice it; but different peoples simply have different ways of expressing their common faith based on who they are as a people. So, the Liturgy of the East is other-wordly and ethereal rather than down to earth and practical; it is mystical and transcendent, focusing us on the world to come, rather than seeking to make itself relevant to this world and its troubles.

This is exactly what the emissaries of the Prince of Kiev found in Constantinople and we’re trying to describe when they said that they did not know if they were in heaven or on earth. And it is also the reason why our Liturgy begins the way it does: “In peace, let us pray to the Lord.” In peace means apart from the concerns of this world. Is it bad to bring our troubles and concerns to the Lord? Certainly not. He expects this of us. But there is a time for every different kind of prayer. At the beginning of the Divine Liturgy we are entering into a mystery which is beyond anything in human experience. We will hear the word of God, we will pray for the Church and the world, and we will have the Lord himself made present before us in the humble forms of bread and wine. But before that happens, we have to be disposed. We have to raise ourselves up away from the cares and concerns of this world so we can meet God on his own terms. There will be time later for talking to God about what troubles us. But as we enter into the Divine Liturgy, all that must be left behind, and we must enwrap ourselves in the peace which only Christ can give. He himself said in the Gospel of St. John: “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you: not as the world gives do I give to you. Let not your hearts be troubled.” And it is in this peace that we must place ourselves as we begin the Divine Liturgy, forgetting all our troubles whatever they may be, entering into that very kind of peace which is described in the very next petition of the Liturgy: “...peace in the whole world, the well being of the Holy Churches of God, and the unity of all....” When we have achieved this peace, then the whole rest of the Liturgy can be prayed with the kind of devotion that it requires of us.

Father Michael Venditti

|