Time to Take the Plunge.

The Tenth Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Kings 17: 17-24.

• Psalm 30: 2, 4-6, 11-13.

• Galatians 1: 11-19.

• Luke 7: 11-17.

The Third Sunday after Pentecost.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Peter 5: 6-11.

• Psalm 54: 23, 17, 19.

• Luke 15: 1-10.

The Third Sunday after Pentecost; the Feast of the Holy Martyr Dorotheus, Bishop of Tyre; and, the Feast of the Holy Martyr Cosmas, Priest of Armenia.

First & third lessons from the pentecostarion, second & fourth from the menaion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Romans 5: 1-10.

• Ephesians 6: 10-17.

• Matthew 6: 22-34.

• Luke 21: 12-19.

FatherVenditti.com

|

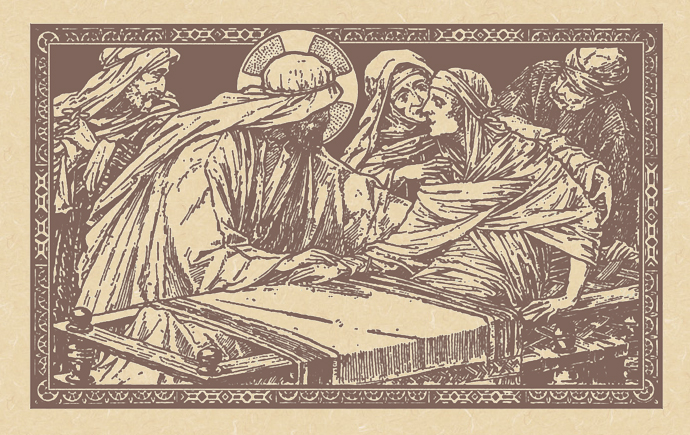

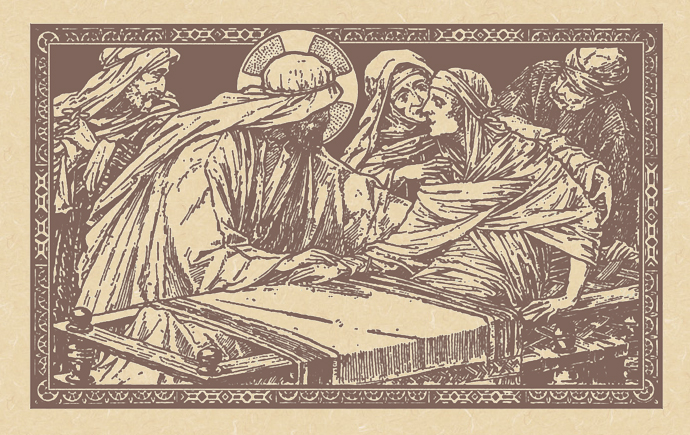

8:13 AM 6/5/2016 — Certainly the most impressive miracles and signs performed by our Lord in the Gospels are those in which He raises someone from the dead: the Synagogue leader’s daughter, the centurion’s manservant, His own relative, Lazarus, and this unknown person of whom we read today, a young man being carried to his grave, accompanied by his grieving mother. The passage from Luke's Gospel has a particular significance for me since, in the Byzantine Rite in which I served for nearly twenty years, the priest chants this Gospel lesson at the doors to the church at the conclusion of every funeral. It’s a sad scene Saint Luke paints for us, which has a happy ending when Christ miraculously restores life to the dead man. It’s a testimony to our Lord’s divinity—for who can raise the dead except God?—as well as His power over death, which He would proclaim most perfectly in his own resurrection. 8:13 AM 6/5/2016 — Certainly the most impressive miracles and signs performed by our Lord in the Gospels are those in which He raises someone from the dead: the Synagogue leader’s daughter, the centurion’s manservant, His own relative, Lazarus, and this unknown person of whom we read today, a young man being carried to his grave, accompanied by his grieving mother. The passage from Luke's Gospel has a particular significance for me since, in the Byzantine Rite in which I served for nearly twenty years, the priest chants this Gospel lesson at the doors to the church at the conclusion of every funeral. It’s a sad scene Saint Luke paints for us, which has a happy ending when Christ miraculously restores life to the dead man. It’s a testimony to our Lord’s divinity—for who can raise the dead except God?—as well as His power over death, which He would proclaim most perfectly in his own resurrection.

But, the table is set, so to speak, for our consideration of what this passage really means by our first lesson from the First Book of Kings, which recounts the most significant of the four most iconic episodes of a highly symbolic nature in the life of the Prophet Elijah, and which also involves a widow. When Elijah arrives in the city of Zarephath it's in the middle of a great famine, and people are dying of starvation left and right. The first person he meets is a poor widow, from whom he asks a cup of water to drink, and a piece of bread to eat. She tells him that she has only enough for herself and her son to eat one last meal together, and once they've finished that, they will die. Elijah tells her not to be afraid, and believe that if she obeys the Lord God, symbolized of course, by obedience to His prophet, all will be well. So, she goes and makes Elijah a little cake with the last measure of flour in her jar, and—low and behold—she ends up having enough food to feed herself and her son for year. Such was the extent that God blessed and rewarded her generosity. And here we can plainly see how she is related to the widow observed by our Blessed Lord in the Gospel lesson, and why these two passages are brought together in today's Mass; because, it's right after the episode of Elijah's meeting with the widow at Zarephath that our first lesson begins, in which her son suddenly dies, and Elijah raises him from the dead. The message is that the reward of blessings that true generosity obtains for us is not a financial one. The fact that the widow of Zarephath was able to eat for a year after making Elijah the little cake is only emblematic of her true reward, which is to be found in eternal life, as symbolized in Elijah raising her son from the dead. Earlier in Luke's Gospel, when our Lord was explaining to the Jews that salvation was not going to be restricted to them alone, He said, “Indeed, I tell you, there were many widows in Israel in the days of Elijah when the sky was closed for three and a half years and a severe famine spread over the entire land. It was to none of these that Elijah was sent, but only to a widow in Zarephath in the land of Sidon” (Luke 4: 25-26 NABRE), His point being that salvation was not to be restricted to the Jews; but, for us, it also means we don't have to be perfect in order to go to our Blessed Lord for help.

The Scriptures speak a metaphorical language that is often foreign to modern ears, for this episode of our Lord raising this man from the dead is more than just a story about Christ’s divinity and His power over death; it is a lesson about sin. All references to death in the Holy Gospel are references to sin. For the Evangelists, sin and death are the same thing: where one is mentioned, the other is understood. Some of you may remember this back when we were looking at the Gospel of Saint John. Just as physical death envelops the body in darkness, so sin envelops the soul in darkness; which is why Saint John describes Christ as “…the light [that] shines in the darkness” (John 1: 5).  Darkness is the quintessential evil for Saint John: sin, error, heresy, disobedience, licentiousness, covetousness, death itself, are all part of the world of darkness in the Holy Gospels. And Christ is that light which shines forth in the darkness and makes it disappear. “Walk as a child of the light,” says our Lord again and again, meaning, “Walk apart from sin.” Because the person who walks in the way of sin must walk in darkness; he prefers the darkness. It is the darkness that hides his sinful deeds from the eyes of others. Sinful deeds are committed in darkness because they must be secret. When Christ admonishes us to walk as children of the light, He is saying, “Have no need for secrets.” Everything we do, no matter how private, should be able to be seen without scandal. Darkness is the quintessential evil for Saint John: sin, error, heresy, disobedience, licentiousness, covetousness, death itself, are all part of the world of darkness in the Holy Gospels. And Christ is that light which shines forth in the darkness and makes it disappear. “Walk as a child of the light,” says our Lord again and again, meaning, “Walk apart from sin.” Because the person who walks in the way of sin must walk in darkness; he prefers the darkness. It is the darkness that hides his sinful deeds from the eyes of others. Sinful deeds are committed in darkness because they must be secret. When Christ admonishes us to walk as children of the light, He is saying, “Have no need for secrets.” Everything we do, no matter how private, should be able to be seen without scandal.

Certainly everyone is entitled to privacy, and all of us have private parts of our lives, our jobs, our marriages, which are not intended for public view. Most of the time it’s a question of appropriateness or modesty. But when a person develops a part of his or her life that must be kept secret because it contradicts the life he or she lives in public—because it would cause a scandal for those who know him—such a person must ask himself if it should be at all.

Now, everybody sins. Saint John says in his First Epistle that anyone who says he is not a sinner makes Christ out to be a liar (cf. I John 1: 8-10). I sin, you sin, we all commit sins. But, the great Father of the Church, Saint John Chrysostom, explains to us that, even though we all sin, it is possible to distinguish what he calls the “evil sinner” from the “good sinner”, as odd as that may sound. The “good sinner”, he says, when he is told he has sinned, reacts with sorrow and begs forgiveness. The “evil sinner”, when his sin is exposed, reacts with indignation, protesting that his privacy has been violated. And over the centuries, no excuse has been used more to defend sinful actions when they are brought to light then the so called right to privacy.

When Jesus raised the dead man to life as we read in the Gospel lesson, Saint Luke added the line, “Then fear seized them all, and they glorified God…” (Luke 7:16 NABRE). It sounds like a contradiction, but it isn’t. Fear seized them because they realized that there is no darkness that can shut out the light of Christ, not even the darkness of death; that the dark rooms that they held in their hearts could be penetrated by Christ. But they glorified God in this because they knew that once a man leaves the darkness and enters into the light—once his sin is exposed and dealt with—then he is free. He is free to walk in the light without shame, no longer having to lurk in the shadows, hiding a part of himself from the eyes of his neighbor, forced by his own choice to live a double life. For then does he realize that whatever pleasure or fulfillment he thought he had in the darkness, it cannot compare to the joy, the rest, the peace given to his soul when there is nothing to hide, when the light can shine brightly on his whole self without cause for shame. And that's why they said of him, “A great prophet has risen among us” and “God has visited His people.”

Every Christian, as some point in his or her life, has to make a choice: we can go on the way most people do, I suppose, living the way we want, running off to the confessional to expiate this or that sin we have committed along the way, hoping that it's enough to warrant eternal life at the end of all things; or, we can realize that that's not enough and take the plunge, convinced that we're much better off going “all the way,” giving over our entire lives to our Blessed Lord, putting off our old ways, and letting the spot-light of truth shine on our whole selves, hiding nothing. After all, Christ was able to raise the widow's son to life only because the widow had accepted the fact that her son was dead, just as He can only expiate and absolve our sins after we've admitted them and acknowledged that we are, in fact, sinners. Then, and only then, are we able to sing with the psalmist with the very words to which we all responded in today's psalm: “Hear, O Lord, and have pity on me; / O Lord, be my helper. / You changed my mourning into dancing; / O Lord, my God, forever will I give you thanks” (Psalm 30: 11-13 NABRE).

|