Arians among us, and the relevance of Nicea.Acts 20:16-18, 28-36; John 17:1-13. The Sunday of the Fathers of the First Ecumenical Council of Nicea. A Postfestive Day of the Ascension.*

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

2:23 PM 6/5/2011 — Next Sunday is Pentecost, and it is the first day of our Summer Schedule of Divine Liturgy at 9:30. It is also the last Sunday before we begin our summer preaching series which, as you know, will focus this year on the Divine Liturgy itself, a subject we explored in the summer of 2005, and which, as you know, I’ve decided to revisit this year. But I am not simply going to pull old homilies out of a file and read them to you; I’ve been working very hard on them this year to make them new and, hopefully, make the Divine Liturgy come alive for you. But we still have two weeks to deal with other things; and today we must visit with the Fathers of the First Ecumenical Council of Nicea, to whom this particular Sunday is dedicated.

St. John, who’s Gospel we read on this feast of the Council Fathers, is so good at describing the transcendent mystery of Christ; which is appropriate, since is was the Fathers of the First Ecumenical Council of Nicea which taught us so many things about the Mystery of Christ.

You might recall that, about two or three years ago on Easter Sunday, I recounted the story of when I left my job to go to the seminary, and how a Buddhist man who worked with me gave me a going-away gift consisting of a book about Jesus written by his local lama; and I mentioned that the book, although very beautiful and well written, completely ignored the fact that Jesus is God and not just a social teacher or philosophical guru. I don’t have that book anymore, but I held on to it for a long time; and, as the years progressed through the seminary, I began to realize that what this lama was saying in this book was very much the same thing that was being said back in the third century, that the Bishops of the Church met in the city of Nicea in Greece in 325 to discuss: is Jesus just a good and wise man, or is he God?

That was the question that preoccupied a priest in Alexandria named Arius. Like many priests of his time—perhaps even of our time—he was looking for a way to make Christianity more palatable to the pagans around him; and he concluded that, if the Church could only see her way clear to present Jesus in the same way the Greeks presented their philosophers—like a philosophical teacher without all this religion stuff getting in the way—people would be more inclined to accept the Church’s message. If we could just leave out all that stuff about morality, and sexual purity, and all these complicated rituals and liturgies, and just preach Christianity as a philosophy of brotherly love, then all kinds of people would flock to the Church. Needless to say, Arius became very popular; and, for a while, his heresy, which became known as Arianism, was so popular that, at one point, most of the world’s bishops and priests believed and were preaching it. That was the question that preoccupied a priest in Alexandria named Arius. Like many priests of his time—perhaps even of our time—he was looking for a way to make Christianity more palatable to the pagans around him; and he concluded that, if the Church could only see her way clear to present Jesus in the same way the Greeks presented their philosophers—like a philosophical teacher without all this religion stuff getting in the way—people would be more inclined to accept the Church’s message. If we could just leave out all that stuff about morality, and sexual purity, and all these complicated rituals and liturgies, and just preach Christianity as a philosophy of brotherly love, then all kinds of people would flock to the Church. Needless to say, Arius became very popular; and, for a while, his heresy, which became known as Arianism, was so popular that, at one point, most of the world’s bishops and priests believed and were preaching it.

And for a while it worked: all kinds of people joined the Church once they were taught that, as a Christian, you didn’t have to really do or believe anything in particular: all you had to do was love one another. It worked, that is, until the first imperial persecutions came along; then everyone left the Church and went back to being pagans again. After all, you need to believe in some kind of God in order to be a martyr; no one’s going to give his life for a mere philosophy—unless you’re Socrates. And when the persecutions were over, and a lot of these people wanted to come back and join the Church again, the Church had a big problem on its hands. You see, the Christians who had remained faithful, who believed in Jesus as God, who lived a moral life, who had accepted torture and death because they believed, were reluctant to have these people back who didn’t really believe in anything and had left the Church at the first sign of trouble; and it was ripping the Church apart. So, the Emperor Constantine called this council of the world’s bishops at Nicea in 325 to decide once and for all whether Jesus was merely a social teacher who should be followed, or was in fact a God who should be worshipped.

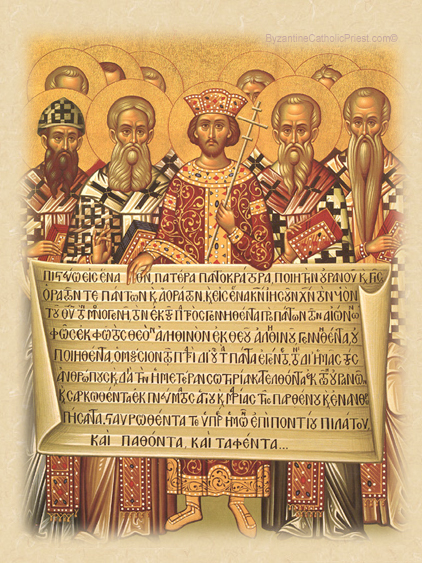

I don’t have to tell you how it turned out, because we’re going to be singing the words of the Council Fathers in just a few moments: the Creed that we sing at every Divine Liturgy is the document that those Fathers produced in response to the Arian heresy; and they decreed that anyone who would call himself a Christian would have to say those words and mean them: “I believe in God, Creator of Heaven and Earth...in one Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God...true God from true God...one in essence with the Father; through whom all things were made...that he came down from heaven as a man, that he suffered and died and rose from the dead, that he ascended into heaven and will come again to judge me according to my deeds.” And it’s the reason that we sing them just before we pray the great Anaphora which transforms simple bread and wine into the real body and blood of Jesus: because I have no right to receive him—nay, even to look upon him in that form—unless I truly believe.

The sad fact is that Arianism never really died with the First Council of Nicea; and you know just as well as I that there are still people, both inside and outside the Church, who think that Jesus is primarily worth something only as a social teacher, that true Christianity means soup kitchens and concern for the homeless and caring about the poor, and has little to do with going to Church or living a moral life. That book that my friend gave me just before I left for the seminary I can excuse, because it was written by someone who was not a Christian; but, the fact is, that many people who are Christians—or who claim to be—could read that book today and not find a single thing wrong with it. And that is the reason we celebrate this particular Sunday; because in celebrating a Sunday dedicated to these Council Fathers, we reject the idea that Christianity is a social philosophy, reaffirm our faith in Christ the God-made-man, and rededicate ourselves to the reality that our religion is not only one of doing good deeds, but of living a good life, and worshipping Christ as the God he truly is.

Father Michael Venditti

* Some older editions of the Typikon refer to this Sunday as The Seventh Paschal Sunday; however, in the Typikon in force in the Ruthenian usage, the day before Ascension Thursday is the Leave-taking of Pascha: the burial shroud of our Lord is removed from the Holy Table, and the Paschal additions to the Liturgy are no longer used. This Sunday falls within the Postfestive period of Ascension, so the Ambon Prayer and Dismissal for Ascension are used; and the Troparia and Kontakia for the Council Fathers are sung along with those for the Ascension. In some other traditions, Pascha might be observed right up until Pentecost, though this does not seem to be consistent with the most ancient observances.

|