The Divine Liturgy, Part One: St. Germanus of Constantinople, and the beauty of not knowning.Heb. 11:33-12:2a; Matt. 10:32-33, 37-38. The First Sunday after Pentecost, known as The Sunday of All Saints.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

10:52 AM 6/19/2011 — As promised, we begin today a discussion of the Divine Liturgy. It’s a tall order because there’s so much which could be said. Into exactly how much detail do we go in a setting like this? If this were nothing more than a presentation on the Liturgy we could talk for hours each time; but this is a homily at the Liturgy itself, so we have to make a few points each week then move on.

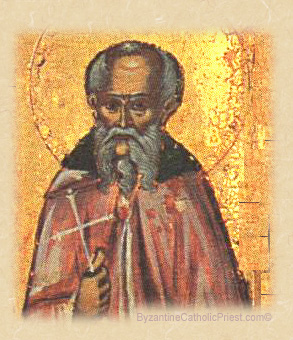

It is impossible to speak about the history of the Byzantine Liturgy without mentioning the name of St. Germanus of Constantinople. St. Germanus was patriarch in the late 7th and early 8th centuries—this was long before the Great Schism between Constantinople and Rome—and he left us a treatise on the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom which remains today the central text for understanding what it is we do when we worship God in Church.  And I remember very clearly, when I first came to the Byzantine Ruthenian Church from the Latin Church, and was just beginning my study of the Byzantine Liturgy, and I was given this ancient document to read, I remember how profoundly shocked I was at some of the things he had to say. As he’s describing the Divine Liturgy as he was celebrating it in his day,—and whenever I quote St. Germanus I'm paraphrasing him—he would come to parts of the service where he would very honestly say, “I don’t know what this means;” but he would go on to say, “That’s OK, because we don’t need to know what it means. God knows what it means.” And I remember very clearly, when I first came to the Byzantine Ruthenian Church from the Latin Church, and was just beginning my study of the Byzantine Liturgy, and I was given this ancient document to read, I remember how profoundly shocked I was at some of the things he had to say. As he’s describing the Divine Liturgy as he was celebrating it in his day,—and whenever I quote St. Germanus I'm paraphrasing him—he would come to parts of the service where he would very honestly say, “I don’t know what this means;” but he would go on to say, “That’s OK, because we don’t need to know what it means. God knows what it means.”

I had been trained, remember, in the Roman Tradition; and, in the Roman Tradition, every liturgical action—every word and every gesture—has a meaning; and knowing what that meaning is, is crucial; because if you don’t know what it means then why are you doing it? When the Second Vatican Council was over, and the Latin Church sat down to reform the Mass of the Roman Rite, the first thing they did was take the Mass of St. Pius V and simply white out anything they found the meaning of which they couldn’t figure out. Now, here I am reading this guy from the 8th Century, the Patriarch of Constatinople, and he’s telling me that not only does he not know what certain parts of the Divine Liturgy mean, but I shouldn’t worry about it and I should do them anyway.

It was a culture shock. But then I began to think: this man is writing about the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom in the 8th Century, and there are already things the meanings of which have been forgotten. Now, how can something done in the 8th Century already be so ancient that no one can remember why they’re doing it? The only explanation is that these things must be incredibly old, probably going back to the practice of the Apostles themselves.

What are some of the things that St. Germanus talks about? Well, take, for example, the singing of the Creed. You have noticed, I’m sure, that during the singing of the Creed, the priest takes the large veil, called an Aer, and waves it over or in front of the gifts. Why is it done? Some people over the years have invented reasons for it: some people will tell you that it represents the breath of the Holy Spirit coming down over the gifts of bread and wine to be consecrated; others will tell you that it symbolizes the Mystery of the Eucharist which is hidden from our sight in the form of bread and wine as if behind a veil; still others will say that it originally was nothing more than the priest trying to shoo flies away from the chalice; and St. Germanus mentions some of these pious theories and says one of them may be true, but in reality we simply don’t know. The fans, called Repidia, which are brought out and held on either side of the priest as he sings the Gospel or distributes Holy Communion: some have said that they were nothing more than fans to keep the priest cool; they always have images of angels on them, so some say they represent the hosts of heaven being present at the Liturgy; and historians like to surmise that they are nothing more than a custom borrowed from the Imperial court; but St. Germanus says very honestly, “We don’t know where they come from. We only know that they’ve always been there.”

But what was even more intriguing than the antiquity of what the Byzantines were doing in church was the reason St. Germanus gave for still doing them: “The fact,” he says, “that something has been done a certain way for as long as anyone can remember is, all by itself, sufficient reason to continue to do it.” Now, those aren’t his actual words—I’m paraphrasing him—but that’s basically what he said. And those words by St. Germanus were my first exposure to the principle of liturgical tradition which is the substratum of everything done in the Eastern Christian Churches today. It is in direct conflict with the notion that everything has to have a meaning and we all have to know what it is.

But St. Germanus doesn’t simply leave us with this innocuous principle and then sign off; he relates it, as a saint should, to our interior life and, in particular, to how it should effect our own personal devotion at the Divine Liturgy. God, he says, is a Mystery. What we think we know about Him is limited because the human mind is limited by its mortality. We relate to God principally though the incarnation by which God became a man in the person of Jesus; but God in His essence is far beyond our comprehension. Is it not reasonable, he asks, that the Liturgy with which we worship Him should also be a Mystery? Do we not, in the Byzantine Tradition, refer to the Blessed Eucharist and to all the sacraments as the Holy Mysteries of the faith? And when we are present at the Divine Liturgy and are praying along with the priest, and things are being done and things are being said and we don’t know what they mean, there we should stop and contemplate how magnificent is God; that, even being so far beyond our understanding, he still chooses to nourish us with His own Body and Blood, giving us a gift the full beauty of which we will never completely understand in his world.

In the weeks that follow, we’ll delve a lot deeper into this great mystery we call the Divine Liturgy and, hopefully, pull back the veil from some of the things we say and do during it; but, in the end, it is important for us to realize that it isn’t our intellectual understanding of the liturgy or its history that makes the service important to us; it’s what the liturgy accomplishes: the bringing into our presence of the blessed Body and Blood of the Lord. So, let’s make a resolution together that, during this summer as we look at this great mystery of faith, we will do so with the intention of increasing our devotion to that most important of acts which defines us as a Church.

Father Michael Venditti

|