Only Her Hairdresser Knows for Sure.

The Eleventh Sunday of Ordinary Time.

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• II Samuel 12: 7-10, 13.

• Psalm 32: 1-2, 5, 7, 11.

• Galatians 2: 16, 19-21.

• Luke 7: 36—8: 3; or, 7: 36-50.

The Fourth Sunday after Pentecost.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Romans 8: 18-23.

• Psalm 78: 9-10.

• Luke 5: 1-11.

The Fourth Sunday after Pentecost; the Fourth Sunday of the Apostles Fast; the Feast of Our Venerable Father Onufrius the Great; and, the Feast of Our Venerable Father Peter of Mount Athos.

First & third lessons from the pentecostarion, second & fourth from the menaion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Romans 6: 18-23.

• Galatians 5: 22—6: 2.

• Matthew 8: 5-13.

• Matthew 11: 27-30.

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:26 AM 6/12/2016 — You've heard me say many times now how the Evangelists don't always present the events of our Lord's life in the same order, or even sometimes reporting all the same events; and yet, the famous narrative of the woman caught in adultery, of which today's rather lengthy Gospel lesson is the sequel, generates more controversy among Scripture scholars than any other set of passages in the Bible. 8:26 AM 6/12/2016 — You've heard me say many times now how the Evangelists don't always present the events of our Lord's life in the same order, or even sometimes reporting all the same events; and yet, the famous narrative of the woman caught in adultery, of which today's rather lengthy Gospel lesson is the sequel, generates more controversy among Scripture scholars than any other set of passages in the Bible.

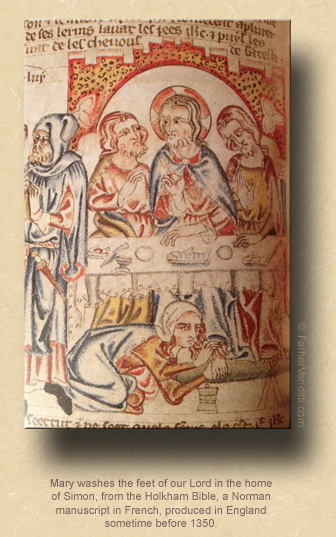

I call it a sequel because most scholars agree that the woman described here bathing our Lord's feet and drying them with her hair is the same one caught in adultery and rescued by our Lord as she was on the brink of being stoned; but, the sturm und drang, if you will, stems from the fact that the two halves of this complete tale don't come from the same Gospel: the woman is caught in the act of adultery and hauled before our Lord in chapter 8 of John's Gospel, and this sequel to the story that we just heard occurs in chapter 7 of Luke. And it isn't just the story itself that causes scholars to believe the one follows the other, but the fact that the first part of this story, found in the Gospel of Saint John, is not written in John's style, nor using John's elegant Greek vocabulary; it is, in fact, written very much in the style of Saint Luke, and doesn't appear at all in the more ancient Greek manuscripts of John's Gospel. That is was originally written by Luke is probable; why it never found its way here into his Gospel we'll never know; how it came to be inserted into John's Gospel is even more mysterious, especially since, depending on what ancient manuscript you're looking at, it can occur in different places.*

And if that isn't enough esoteric Biblical controversy for you, I've got more. Pope Saint Gregory the Great, in the sixth century, was the first to identify this woman in John 8 and Luke 7 with Mary Magdalene (cf. Homily 33 on the Gospels). While Scripture scholars will continue to debate that issue—and Protestants, for the most part, reject it—the identification has become integral to Catholic devotion to the Magdalene. When I preached last year on the Memorial of Saint Mary Magdalene and embraced full throttle Saint Gregory's identification, I got more e-mails from readers of my web site than I had ever gotten about any other homily, all of them taking umbrage with my siding with Pope Gregory on the issue, as most scholars reject the identification. But, being old fashioned, I responded that, since Pope Gregory made his identification, the Church has said nothing definitive on the issue since, so as far as I'm concerned the matter is settled. In fact, the only thing said by any pope since Gregory the Great about Mary Magdalene was said last week by Pope Francis, when he promoted the Memorial of Saint Mary Magdalene to the rank of a feast. He did it, he said, to emphasize the role of women in the Church. I think it's good that her feast has been upgraded on the calendar, but not for any politically correct reason; I think she is important because of the spiritual realities she teaches us, which she would teach us regardless of her sex. And what is it exactly Mary Magdalene—or whomever you want to believe this woman is—teaches us?

It's not uncommon—and you have have heard it, I'm sure—to hear a comedian introduce a stand-up routine by pointing out that he or she was raised as a Catholic, and therefore grew up with a sense of guilt.  This, then, becomes the premise of a series of jokes—sometimes funny, mostly not—which usually ends up holding the Church and the Faith up to ridicule. The reason these jokes work is because of the wide-spread assumption, foisted on us by modern pop-psychology, that guilt is something bad, and that feeling guilty is, somehow, psychologically unhealthy. This, then, becomes the premise of a series of jokes—sometimes funny, mostly not—which usually ends up holding the Church and the Faith up to ridicule. The reason these jokes work is because of the wide-spread assumption, foisted on us by modern pop-psychology, that guilt is something bad, and that feeling guilty is, somehow, psychologically unhealthy.

Not only is there nothing wrong with guilt—not only is it not unhealthy to feel guilty when one has sinned—but, in the context of our relationship with God, it is absolutely essential. The premise that guilt is unhealthy is predicated on the presumption that there's no such thing as sin, but there is. This woman about whom we read today—assuming she was Mary Magdalene—was one of the most important and outstanding disciples of our Lord, and would not have become such had she not felt guilt. Guilt, and the feelings of remorse that go with it, is responsible for the lives of the some of the greatest saints in the history of the Church, many of them martyrs. Guilt is the seedbed of conversion; without guilt we do not repent of our sins, and without repentance we don't grow in Grace.

Non-Catholics and Catholics poorly formed in their Faith see guilt as an enemy of happiness, but exactly the opposite is true. Learning to recognize our sins and confessing them breaks down the walls that impede our spiritual growth. The more we become conscious of sin in our lives, the more we become receptive to Grace, and the closer we grow to our Lord and to that final end which is the reason for our life on this earth. We examine our consciences regularly and confess our sins frequently because it keeps our souls cleansed in anticipation of death, but also because, by routinely stripping away the vestiges of even the smallest venial sins, the pathways of Grace are plowed clear of whatever would hinder our growth in holiness. What results is a kind of spiral upward into union with God: the more we reflect on our sins and confess them, the more we become sensitive to the presence of sin in our lives, and become aware of faults that we didn't even recognize as faults before. This is how ordinary people grow in Grace and become great saints.

Shun the notion of guilt and sin, and the process is reversed: we reserve confession only for the big mortal sins, we don't examine our consciences regularly, and we become desensitized to venial faults, with the result that we begin to make excuses even for mortal sins. Confession, then, becomes a burden that we endure when required at Easter time, and growth in Grace is practically impossible. We tumble into a downward spiral, beset by temptation at every turn, receiving little if any Grace from our reception of Holy Communion, and coming to view Christian living as a struggle rather than a joy.

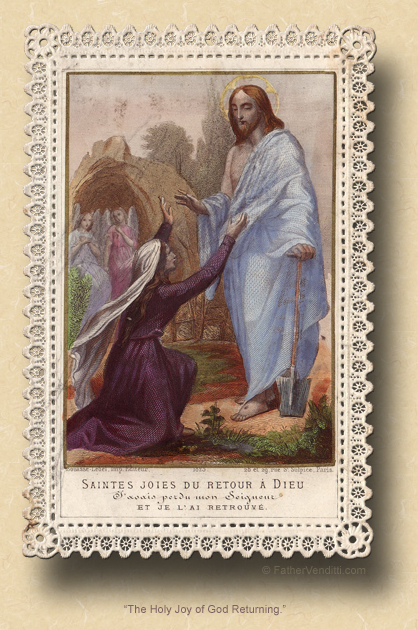

The Gospel lesson for this Sunday does not present to us the story of Mary Magdalene's conversion and repentance; instead, it shows us the fruits of it. Having embraced her guilt, motivated by it to change her life and devote her life to Christ, she was given a Grace that was denied even to the Apostles: she, remember, was the very first to see the Risen Lord on Easter Sunday. There is a lesson for us in that: Grace comes only to those humble enough to know they need it.

* The story of the woman caught in adultery (John 8: 1-11) is found mostly in old Latin manuscripts of John's Gospel, and in different places, sometimes at the beginning of chapter 8 as in modern Bibles, sometimes after 7: 36 just prior to our Lord's discourse on the last day of Pentecost, and sometimes at the very end of the Gospel. A few manuscripts include it at the end of Luke 21 just before the beginning of the Passion narrative, or at the end of his Gospel after the resurrection. Though Luke is generally regarded as the author, it is clear that it was never an original part of either Gospel, but inserted later, probably because of the allusion to Jeremiah 17: 13. Nevertheless, the Catholic Church has always accepted it as canonical, and part of the Gospel of Saint John; Saint Jerome certainly did.

|