How to spot the Godless: they become angry when you offer them freedom from their passions.Acts 2:1-11; John 7:37-52, 8:12. Pentecost.

Return to ByzantineCatholicPriest.com. |

11:04 AM 6/12/2011 ó I would like to focus today on one particular curious thing that St. John mentions in the Gospel passage that we just read.

He begins by telling us that it was the last day of the Great Feast, which alerts us to the fact that Pentecost was already a Jewish holiday long before it became a Christian one. It was, in fact, the last day of a 50 day celebration of the harvest of first fruits which begins at the end of Passover. Among the Jews even today, itís regarded as the second most important feast in their calendar, called the Feast of Booths or the Feast of Tabernacles, or, as is sometimes mentioned in the Gospels, the feast of Pentecost.

The Christians, of course, assigned to it a new meaning based on the fact that it was on this Jewish feast that Jesus, having ascended to his Father, sent down the Holy Spirit to the Apostles and inaugurated their mission to establish his Church throughout the world; the account of which the cantor sang for us in the Apostolic reading. The events described by St. John in todayís Gospel also occurred on Pentecost, but one year earlier. Jesus is in Jerusalem, in the Temple of Solomon, and gives a speech. St. John records for us the speech, as well as the reactions of some of those listening. And this is what drew my attention.

The speech our Lord gives is, of course, about the Spirit which he will send upon the Church once he has died and risen and ascended to heaven. He quotes the Old Testament Prophets, as he always does, referring to their reference to God sending streams of flowing water, which he indicates is actually a description of the grace of the Holy Spirit that will come down upon the Church after the Paschal Mystery is fulfilled, anticipating the sacrament of Baptism by which the Holy Spirit would be given to us as individuals. And buried in our Lordís words is the truth that this Holy Spirit, once received, would enable the Christian to live a life of grace, and transcend the limitations of a fallen human nature. Thus, the person who receives this grace would become able to resist temptation and perform acts of great virtue, even though it is against his natural inclinations to do so.

The reaction of some of his audience is whatís interesting. Some of them are quite moved, and begin to wonder if Jesus is some reincarnation of John the Baptist. But there were some others there whom, as St. John describes it, didnít quite like the message they were hearing, and started to make up some reasons why Jesus didnít know what he was talking about. The chief objection seems to have been that Jesus comes from Galilee, whereas the prophets always spoke of the Christ coming from the city of David, which is Bethlehem. Itís confusing to us because we know that Jesus was born in Bethlehem; but they didnít know that, because Jesus, although born in Bethlehem, was raised in Galilee; so most people thought he was a Galilean by birth, when he was, in fact, a Davidian by birth just as the prophets foretold.

Itís a stupid argument anyway. Where someone is born does not effect whether what he says is true. The excuse they give for rejecting his messageóthat heís a Galileanóis just that: an excuse, which they have invented to mask the real reason they reject his message, which is that they donít like what his message is challenging them to be. The idea that God is going to send a supernatural gift of grace which will enable us to transcend our human nature, deny ourselves, and live lives free from sin regardless of the weakness of the body, is not a message thatís going to be well received by someone who is a slave to his passions. After all, when someone succumbs to temptation and sins, what is one of the first things he says in defense of himself? ďItís only natural.Ē Which is true. It is only natural. But the Christian is not confined to what is natural, which is exactly what Jesus is trying to explain here. The Christian who has received the grace of the Holy Spirit in Baptism has been given the ability to resist what is natural and do what is supernatural. He does not have to eat simply because he is hungry, he does not have to have sex simply because heís aroused, he does not have to steal simply because heís in need, he does not have to lie simply because the truth would do him harm; and we can go through all the Commandments if you want. The bottom line is that the Christian does not have to satisfy his natural appetites; he can resist them. The grace of the Holy Spirit makes it possible for him to live a life outside of the influence of his own human nature; and by so doing, to live a life in conformity to the Commandments of God and, thereby, make himself worthy of the kingdom of heaven. Itís a stupid argument anyway. Where someone is born does not effect whether what he says is true. The excuse they give for rejecting his messageóthat heís a Galileanóis just that: an excuse, which they have invented to mask the real reason they reject his message, which is that they donít like what his message is challenging them to be. The idea that God is going to send a supernatural gift of grace which will enable us to transcend our human nature, deny ourselves, and live lives free from sin regardless of the weakness of the body, is not a message thatís going to be well received by someone who is a slave to his passions. After all, when someone succumbs to temptation and sins, what is one of the first things he says in defense of himself? ďItís only natural.Ē Which is true. It is only natural. But the Christian is not confined to what is natural, which is exactly what Jesus is trying to explain here. The Christian who has received the grace of the Holy Spirit in Baptism has been given the ability to resist what is natural and do what is supernatural. He does not have to eat simply because he is hungry, he does not have to have sex simply because heís aroused, he does not have to steal simply because heís in need, he does not have to lie simply because the truth would do him harm; and we can go through all the Commandments if you want. The bottom line is that the Christian does not have to satisfy his natural appetites; he can resist them. The grace of the Holy Spirit makes it possible for him to live a life outside of the influence of his own human nature; and by so doing, to live a life in conformity to the Commandments of God and, thereby, make himself worthy of the kingdom of heaven.

Now, thatís a lot to squeeze out of two sentences in todayís Gospel, but it doesnít even stop there; because Jesus, having sent to us the Holy Spirit, which would be enough, gives us even more. The inspired word of God in the Scriptures, and the teachings of the Fathers of the Church, nourish our soul with truth; the Spirit likewise enlivens Christís Holy Church to teach us how to navigate the vicissitudes of an ever-changing world; the Holy Mystery of Matrimony gives us a way to focus our natural passions into creative ends; our own prayers bring Christ to us in friendship, just as he said, ďWhenever two or three are gathered in my name, there I am among themĒ; and the gift of the Holy Priesthood makes the greatest helps of all available to us: the gift of Christ himself in the Blessed Eucharist, and the continual forgiveness of sins in confession. One is tempted to say, ďAll this, and the Holy Spirit, too!Ē With all this, how could one fail to reach heaven?

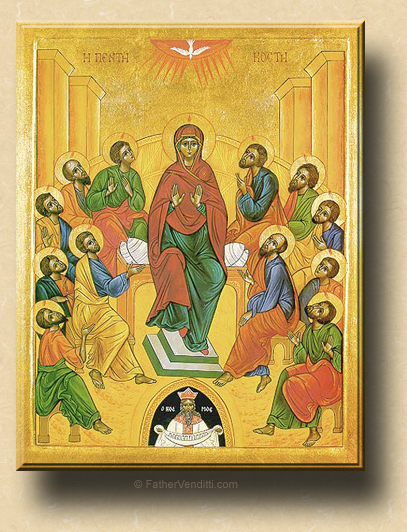

But the fact is that some people do fail to reach heaven, not because they donít have what they need, but because they refuse to accept it. Thatís why the resistance of some of the people in our Lordís audience on the Feast of Pentecost is so disturbing. They had been told that they would be given the ability to save themselves, and were actively looking for a way not to believe it. Why? A glance at the icon for this feast tells us the reason.

In almost every icon of Pentecost, at the bottom there is a black semicircle with a man inside. He wears a crown, indicating that he is someone of worldly importance. In both fists he grasps tightly a sack or hamper. Iconographers refer to him with the name "Cosmos," the Greek word for "world." His hamper contains all his worldly possessions, symbolizing his attachment to this world. The grace of the Holy Spirit cannot reach him in the abyss; and he cannot climb out of it so long as he keeps his grasp on the passions of the world which weigh him down. Freedom from the passions which enslave him is available to him;óall he has to do is let goóbut he won't. For all of his wealth, all of his independence, all of his pleasures, all of his insistence that no one will tell him how to live, he is a slave in the true sense of the word. From his dark abyss he scoffs at the Christian, labeling the Christian as a slave because he does this and denies himself that, completely oblivious to the fact that he's the one in the hole.

There is no more cruel a slavemaster than ourselves; and there is no greater freedom than that offered by Christ: the freedom from our own desires.

Father Michael Venditti

|