Let Not This Sacred Season Leave Us as It Found Us.

Pentecost Sunday.

Lessons from the primary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite, at the Vigil:

• Genesis 11: 1-9.

• Exodus 19: 3-8, 16-20.

• Exekiel 37: 1-14.

• Joel 3: 1-5.

• Psalm 104: 1-2, 25, 35, 27-30.

• Romans 8: 22-27.

• John 7: 37-39.

…and, at Mass During the Day:

• Acts 2: 1-11.

• Psalm 104: 1, 24, 29-31, 34.

• I Corinthians 12: 3-7, 12-13.

• [Sequence (optional)] Veni, Sancte Spiritus…*

• John 20: 19-23.

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Acts 2: 1-11.

• John 7: 37-52; 8: 12.

Whitsunday.**

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:***

• Acts 2: 1-11.

• [The Gradual is omitted].

• [Sequence] Veni, Sancte Spiritus…*

• John 14: 23-31.

FatherVenditti.com

|

6:53 AM 5/31/2020 — The Gospel lesson we just heard for today's feast, from chapter twenty of the Blessed Apostle and Evangelist John, presents to us what you might not expect on Pentecost: the Apostles before the descent of the Holy Spirit, receiving a visit from the Risen Lord, who gives them the power to forgive sins, thus instituting the Sacrament of Confession. Why a Gospel lesson about Confession on Pentecost Sunday? There is, of course, a reason; and, to understand it, it helps to look at the Gospel lesson which was read last evening during the Mass for the Vigil of Pentecost. That Gospel is from all the way back in chapter seven, in which the Blessed Apostle John recounts our Lord's first visit to Jerusalem on the day of Pentecost. There he says, “On the last and greatest day of the feast Jesus stood there and cried aloud, 'If any man is thirsty, let him come to me, and drink...'" (John 7: 37 Knox); which alerts us to the fact that Pentecost was already a Jewish holiday long before it became a Christian one. It was, in fact, the last day of a 50 day celebration of the harvest of first fruits which began at the end of Passover. Among the Jews even today, it’s regarded as the second most important feast on their calendar, called the Feast of Booths or the Feast of Tabernacles, or, as is sometimes mentioned in the Gospels, the feast of Pentecost. 6:53 AM 5/31/2020 — The Gospel lesson we just heard for today's feast, from chapter twenty of the Blessed Apostle and Evangelist John, presents to us what you might not expect on Pentecost: the Apostles before the descent of the Holy Spirit, receiving a visit from the Risen Lord, who gives them the power to forgive sins, thus instituting the Sacrament of Confession. Why a Gospel lesson about Confession on Pentecost Sunday? There is, of course, a reason; and, to understand it, it helps to look at the Gospel lesson which was read last evening during the Mass for the Vigil of Pentecost. That Gospel is from all the way back in chapter seven, in which the Blessed Apostle John recounts our Lord's first visit to Jerusalem on the day of Pentecost. There he says, “On the last and greatest day of the feast Jesus stood there and cried aloud, 'If any man is thirsty, let him come to me, and drink...'" (John 7: 37 Knox); which alerts us to the fact that Pentecost was already a Jewish holiday long before it became a Christian one. It was, in fact, the last day of a 50 day celebration of the harvest of first fruits which began at the end of Passover. Among the Jews even today, it’s regarded as the second most important feast on their calendar, called the Feast of Booths or the Feast of Tabernacles, or, as is sometimes mentioned in the Gospels, the feast of Pentecost.

The Christians, of course, assigned to it a new meaning based on the fact that it was on this Jewish feast that Jesus, having ascended to His Father, sent down the Holy Spirit to the Apostles and inaugurated their mission to establish His Church throughout the world, the account of which we heard in our first lesson today from the Acts of the Apostles. The events described by St. John in chapter seven, from which I just quoted, also occurred on Pentecost, but one year earlier. Jesus is in Jerusalem, in the Temple of Solomon, and gives a speech. St. John records for us the speech, as well as the reactions of some of those listening.

The speech our Lord gives is, of course, about the Spirit which he will send upon the Church once he has died and risen and ascended to heaven. He quotes the Old Testament Prophets, as He always does, referring to their reference to God sending streams of flowing water, which He indicates is actually a description of the grace of the Holy Spirit that will come down upon the Church after the Paschal Mystery is fulfilled, anticipating the sacrament of Baptism by which the Holy Spirit would be given to us as individuals. And buried in our Lord’s words is the truth that this Holy Spirit, once received, would enable the Christian to live a life of grace, and transcend the limitations of a fallen human nature. Thus, the person who receives this grace would become able to resist temptation and perform acts of great virtue, even though it is against his natural inclinations to do so.

The reaction of some in our Lord's audience is what’s interesting. Some of them are quite moved, and begin to wonder if Jesus is some reincarnation of John the Baptist. But there were some others there whom, as St. John describes it, didn’t quite like the message they were hearing, and started to make up some reasons why Jesus didn’t know what He was talking about. The chief objection seems to have been that Jesus comes from Galilee, whereas the prophets always spoke of the Christ coming from the city of David, which is Bethlehem. It’s confusing to us because we know that Jesus was born in Bethlehem; but they didn’t know that, because Jesus, although born in Bethlehem, was raised in Galilee; so most people thought He was a Galilean by birth, when He was, in fact, a Davidian by birth just as the prophets foretold.

It’s a stupid argument anyway. Where someone is born does not effect whether what he says is true. The excuse they give for rejecting his message—that he’s a Galilean—is just that: an excuse, which they have invented to mask the real reason they reject His message, which is that they don’t like what His message is challenging them to be.  The idea that God is going to send a supernatural gift of grace which will enable us to transcend our human nature, deny ourselves, and live lives free from sin regardless of the weakness of the body, is not a message that’s going to be well received by someone who is a slave to his passions. After all, when someone succumbs to temptation and sins, what is one of the first things he says in defense of himself? “It’s only natural.” Which is true. It is only natural. But the Christian is not confined to what is natural, which is exactly what Jesus is trying to explain here. The Christian who has received the grace of the Holy Spirit in Baptism has been given the ability to resist what is natural and do what is supernatural. He does not have to eat simply because he is hungry, he does not have to steal simply because he’s in need, he does not have to act impure simply because he’s aroused, he does not have to lie simply because the truth would do him harm; and we can go through all the Commandments if you want. The bottom line is that the Christian does not have to satisfy his natural appetites; he can resist them. The grace of the Holy Spirit makes it possible for him to live a life outside of the influence of his own human nature and, by so doing, live a life in conformity to the Commandments of God, thereby making himself worthy of the kingdom of heaven. The idea that God is going to send a supernatural gift of grace which will enable us to transcend our human nature, deny ourselves, and live lives free from sin regardless of the weakness of the body, is not a message that’s going to be well received by someone who is a slave to his passions. After all, when someone succumbs to temptation and sins, what is one of the first things he says in defense of himself? “It’s only natural.” Which is true. It is only natural. But the Christian is not confined to what is natural, which is exactly what Jesus is trying to explain here. The Christian who has received the grace of the Holy Spirit in Baptism has been given the ability to resist what is natural and do what is supernatural. He does not have to eat simply because he is hungry, he does not have to steal simply because he’s in need, he does not have to act impure simply because he’s aroused, he does not have to lie simply because the truth would do him harm; and we can go through all the Commandments if you want. The bottom line is that the Christian does not have to satisfy his natural appetites; he can resist them. The grace of the Holy Spirit makes it possible for him to live a life outside of the influence of his own human nature and, by so doing, live a life in conformity to the Commandments of God, thereby making himself worthy of the kingdom of heaven.

Now, that’s a lot to squeeze out of two sentences of Saint's John's Gospel, but it doesn’t even stop there; because Jesus, having sent to us the Holy Spirit, which would be enough, gives us even more: the inspired word of God in the Scriptures, and the teachings of the Fathers of the Church, nourish our souls with truth; the Spirit likewise enlivens Christ’s Holy Church to teach us how to navigate the vicissitudes of an ever-changing world; the Holy Sacrament of Matrimony gives us a way to focus our natural passions into creative ends; our own prayers bring Christ to us in friendship, just as He said, “Whenever two or three are gathered in my name, there I am among them”; and, the gift of the Holy Priesthood makes the greatest helps of all available to us: the gift of Christ himself in the Blessed Eucharist, and the continual forgiveness of sins in confession. One is tempted to say, “All this, and the Holy Spirit, too!” With all this, how could one fail to reach heaven?

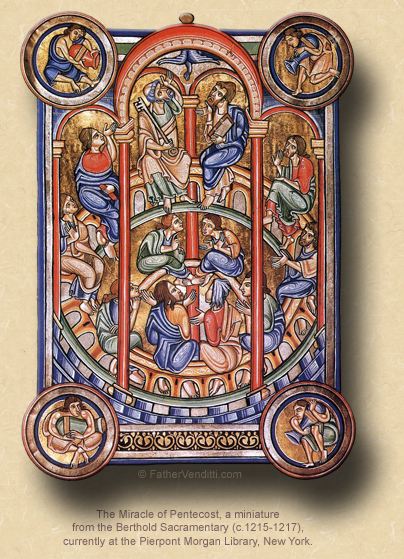

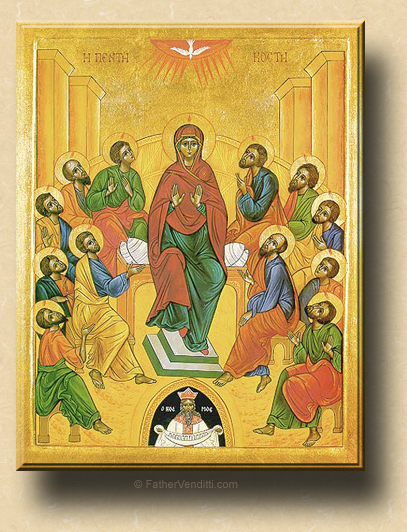

But we know, from many various apparitions of our Blessed Mother, at Fatima and elsewhere, and from the testimony of many saints who were privy to locutions from both our Lord and our Lady, that some people do fail to reach heaven, not because they don’t have what they need, but because they refuse to accept it. That’s why the resistance of some of the people in our Lord’s audience on the Feast of Pentecost is so disturbing. They had been told that they would be given the ability to save themselves, and were actively looking for a way not to believe it. Why? A glance at the Byzantine icon for the feast of Pentecost tells us the reason. I don't have one on hand, but I can describe it to you.

The icon for the Feast of Pentecost is very distinctive: it shows the Apostles gathered in the upper room, sometimes in the presence of the Mother of God and sometimes not; it depends on the preference of the particular iconographer; but, one element of the icon of Pentecost is always the same: at the bottom of the scene, underneath where the Apostles are gathered, there is a black semicircle with a man inside. He wears a crown, indicating that he is someone of worldly importance. In both fists he grasps tightly a sack or hamper. Iconographers refer to him with the name "Cosmos," the Greek word for "world."  His hamper contains all his worldly possessions, symbolizing his attachment to this world; indeed, the black hole in which he's pictured represents the dark world in which he lives; so, whereas the Apostles shown above him are bathed in the light of the Holy Spirit, he is in total darkness. The grace of the Holy Spirit cannot reach him in this abyss, and he cannot climb out of it so long as he keeps his grasp on the passions of the world which weigh him down. Freedom from the passions which enslave him is available to him;—all he has to do to get out of his dark hole is let go—but he won't. For all of his wealth, all of his independence, all of his pleasures, all of his insistence that no one will tell him how to live, he is a slave in the true sense of the word. From his dark abyss he scoffs at the Christian, labeling the Christian as a slave because he does this and denies himself that, completely oblivious to the fact that he's the one in the hole. His hamper contains all his worldly possessions, symbolizing his attachment to this world; indeed, the black hole in which he's pictured represents the dark world in which he lives; so, whereas the Apostles shown above him are bathed in the light of the Holy Spirit, he is in total darkness. The grace of the Holy Spirit cannot reach him in this abyss, and he cannot climb out of it so long as he keeps his grasp on the passions of the world which weigh him down. Freedom from the passions which enslave him is available to him;—all he has to do to get out of his dark hole is let go—but he won't. For all of his wealth, all of his independence, all of his pleasures, all of his insistence that no one will tell him how to live, he is a slave in the true sense of the word. From his dark abyss he scoffs at the Christian, labeling the Christian as a slave because he does this and denies himself that, completely oblivious to the fact that he's the one in the hole.

And that is why Holy Mother Church gives us a Gospel about Confession on the Feast of Pentecost. It is that sacrament which not only frees us from the burden of the sins we have already committed, but which also gives us the grace we need to avoid sin in the future. That's why we go to confession frequently, not only when we're conscious of a mortal sin, because Christ, in the sacrament of Confession, does two things, not just one: he forgives the sins we've committed, but he also imparts to us grace to avoid sinning in the future; and, even if we're fortunate enough not to need the one, we always need the other.

With the Feast of Pentecost, the Easter Season comes to a close; but, as we bid farewell to the festive character of the season, we should resolve not to bid farewell to all the good resolutions and progress we have made from Ash Wednesday until now; and, in that light I'll leave you to consider the words of one of my favorite saints, Blessed John Henry Newman, who summed up the Feast of Pentecost this way:

May we, one and all, set forward with this season, when the Spirit descended, that so we may grow in grace, and in the knowledge of our Lord and Saviour! Let those who have had seasons of seriousness, lengthen them into a life; and let those who have made good resolves in Lent, remember them in Eastertide; and let let those who have hitherto lived religiously, learn devotion; and let those who have lived in good conscience, learn to live by faith; and let those who have made a good profession, aim at consistency; and let those who take pleasure in religious worship, aim at inward sanctity; and let those who meditate, forget not mortification. Let not this sacred season leave us as it found us; let it leave us, not as children, but as heirs and as citizens of the kingdom of heaven.††

* Come, Holy Ghost, send down those beams,

which sweetly flow in silent streams

from Thy bright throne above.

O come, Thou Father of the poor;

O come, Thou source of all our store,

come, fill our hearts with love.

O Thou, of comforters the best,

O Thou, the soul's delightful guest,

the pilgrim's sweet relief.

Rest art Thou in our toil, most sweet

refreshment in the noonday heat;

and solace in our grief.

O blessed Light of life Thou art;

fill with Thy light the inmost heart

of those who hope in Thee.

Without Thy Godhead nothing can,

have any price or worth in man,

nothing can harmless be.

Lord, wash our sinful stains away,

refresh from heaven our barren clay,

our wounds and bruises heal.

To Thy sweet yoke our stiff necks bow,

warm with Thy fire our hearts of snow,

our wandering feet recall.

Grant to Thy faithful, dearest Lord,

whose only hope is Thy sure word,

the sevenfold gifts of grace.

Grant us in life Thy grace that we,

in peace may die and ever be,

in joy before Thy face. Amen. Alleluia.

*** "Whitsunday" is nothing more than an anglicized name for Pentecost. Most editions of the Missal of St. John XXIII produced for use in English speaking countries use the title, but still refer to the octave and season following as those of Pentecost. In non-English speaking countries, the title "Whitsunday" is unknown.

The name is a contraction of “White Sunday,” and there are several theories about the meaning. Some have suggested that it is an Anglo-Saxon word derived from the Icelandic, hvitasunnu-dagr; this is supported by the fact that, in English, the feast was always known as Pentecoste until the time of the Norman Conquest, when the word hwitte (white) was often confused with wit (understanding). The Augustinian Canon, John Mirk (c. 1382-1414) of Lilleshall Abbey, Shropshire, says: “Goode men and woymen, as ʒe knowen wele all, þys day ys called Whitsonday, for bycause þat þe Holy Gost as þys day broʒt wyt and wysdome ynto all Cristes dyscyples.” Thus, he thought the root of the word was "wit" (formerly spelled "wyt" or "wytte"), and Pentecost was so-called to signify the outpouring of the wisdom of the Holy Ghost on Christ's disciples. Another theory posits that the name refers to the white garments worn by catechumens, who were sometimes baptized on this day. In any case, it is a fact that white was traditionally worn for Pentecost in the West, while Green was—and remains—the color for the feast in the East. The use of red for celebrations of the Holy Spirit in the West did not become popular until relatively late in the Middle Ages, and was not formally codified until the reforms following the Council of Trent.

† For the lessons for the Vigil of Pentecost in the extraordinary form, cf. the post and accompanying note from yesterday's homily.

†† Sermons on Subjects of the Day, XI, “Christian Nobleness” (Whitsuntide).

|