We Are Never Truly Alone.

The Fifth Sunday of Easter.

Lessons from the secondary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Acts 9: 26-31.

• Psalm 22: 26-28, 30-32.

• I John 3: 18-24.

• John 15: 1-8.

The Fourth Sunday after Easter.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• James 1: 17-21.

• John 16: 5-14.*

The Sunday of the Samaritan Woman.

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the typicon of the Byzantine-Ruthenian Rite:

• Acts 11: 19-26, 29-30.

• John 4: 5-42.

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:44 AM 5/3/2015 — Yesterday we had a particularly busy day here at the Shrine: it was the first time that we decided to observe the First Saturday of the Month in a major way, with a series of outdoor events, and I was chosen to be both the guest speaker and homilist at Holy Mass, so I'm all talked out. But, it's Sunday, and I can't leave you with nothing, so I would like to offer you just one thought from the many points I tried to made yesterday. 8:44 AM 5/3/2015 — Yesterday we had a particularly busy day here at the Shrine: it was the first time that we decided to observe the First Saturday of the Month in a major way, with a series of outdoor events, and I was chosen to be both the guest speaker and homilist at Holy Mass, so I'm all talked out. But, it's Sunday, and I can't leave you with nothing, so I would like to offer you just one thought from the many points I tried to made yesterday.

Even though it was First Saturday, and my particular assignment was to preach on the First Saturday devotion and the first of the blasphemies for which our Lady asked us to make reparation, it was also the Memorial of Saint Athanasius, so I was able to work him into my homily. Unfortunately, for those of us who may attend Holy Mass only on Sundays, we miss hearing about many of these wonderful saints whom the Church celebrates throughout the year, and Saint Athanasius is certainly one of the most important.

In the fourth century, when Athanasius was Bishop of Alexandria in Egypt, Northern Africa and the Middle East were almost entirely Catholic. In fact, the Roman Provence of Northern Africa was the most vibrant and active part of the Church, more so than Rome itself. And, as we know from our own experience here in America, when a local Church becomes large and prosperous and rich, it easily falls into sin. Alexandria was the biggest diocese in the Catholic Church—the Chicago or New York of its day—and was the home of the biggest heresy that ever threatened the True Faith. It all started with a priest of Athanasius' own diocese named Arius. Like many priests of his time—perhaps even of our time—he was looking for a way to make Christianity more palatable to the pagans around him; and he concluded that, if the Church could only see her way clear to present Jesus in the same way the Greeks presented their philosophers—like a philosophical teacher without all this religion stuff getting in the way—people would be more inclined to accept the Church’s message. If we could just leave out all that stuff about morality, and all these complicated rituals and liturgies, and just preach Christianity as a philosophy of brotherly love, then all kinds of people would flock to the Church.

Needless to say, Arius became very popular; and, for a while, his heresy, which became known as Arianism, was so popular that, at one point, most of the world’s bishops and priests believed and were preaching it. In fact, from the latter part of the third century right through to the middle of the fourth, every single bishop of the Catholic Church in Northern Africa, the largest Catholic region in the world, was preaching that Jesus was a very nice and grace-filled man, but not God—every bishop, that is, except one. Athanasius stood alone. The Pope was on his side, but the Pope was far away in Rome, and could do nothing to help other than write letters, which were all, of course, politely ignored.

For seventeen years, Athanasius was exiled from his diocese, unable to care for his flock, while heretics in his own diocese led countless souls away from the worship of Jesus Christ as Lord and God. When the Emperor, who himself had been an Arian heretic, called an ecumenical council of the Church at Nicea to try and heal the Church's divisions, Athanasius, still just a deacon at the time, stood in the middle of that assembly and shouted loud and clear words that would forever become engrained in the hearts of Christians for centuries: that Jesus Christ is God from God, Light from Light, True God from True God, begotten and not made, con-substantial with the Father, and through Him all things were made. The Church took those words, and put them into a creed, and commanded that every Christian, for all time, would be required to recite those words, and believe them, as a condition for receiving the Sacred Body and Precious Blood of our Lord, God and Savior, Jesus Christ.

But think of what it must have been like for Athanasius, to believe something with all your heart, and to be the only person around you to believe it. Athanasius was a great bishop and a great theologian, but he was also a man. How lonely he must have felt, and how tempted he must have been, at times, to turn away from the Faith he knew was true and go along with the crowd. What was it that sustained him? What was it that gave him the strength to resist the temptation to get along and thus remain faithful to the true Faith for all those years? It could only have been a deep, personal friendship with the Blessed Lord Whose divinity he defended so eloquently.

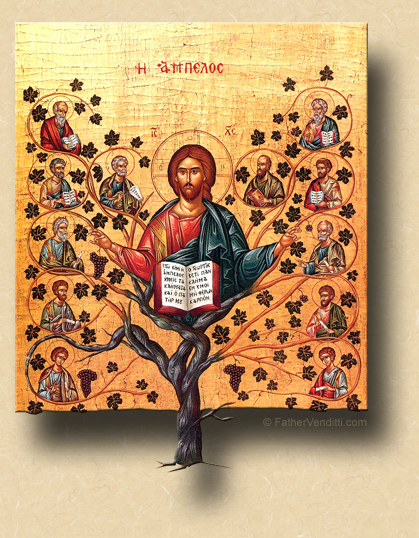

“I am the vine, you are the branches,” says the Lord in today's Gospel lesson; “…without me you can do nothing” (John 15: 5 NABRE). And, on those occasions—and we all have them—when we find ourselves alone, and our devotion to the Church and to the Faith makes us feel like outsiders, even sometimes among our own families and friends, let us turn to the Lord in faith, and remember that those who love God are never truly alone.

* In the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite, from Easter Saturday until the end of Paschaltide, the Gradual Psalm is omitted.

|