The Calm After the Storm.

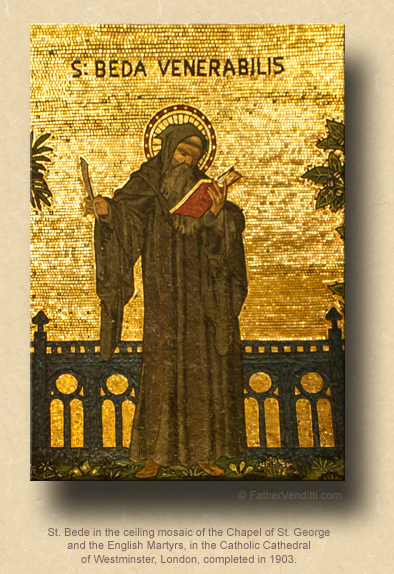

The Fifth Saturday of Easter; the Memorial of Saint Bede the Venerable, Priest & Doctor of the Church; the Memorial of Saint Gregory VII, Pope; or, the Memorial of Saint Mary Magdalene de' Pazzi, Virgin.*

Lessons from the feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Acts 16: 1-10.

• Psalm 100: 1-3, 5.

• John 15: 18-21.

|

If a Mass for St. Bede is taken, lessons from the feria as above, or from the proper:

• I Corinthians 2: 10-16.

• Psalm 119: 9-14.

• Matthew 7: 21-29.

… or, any lessons from the common of Doctors of the Church; or, the common Holy Men & Women for a Monk.

|

|

If a Mass for Pope St. Gregory is taken, lessons from the feria as above, or from the proper:

• Acts 20: 17-18, 28-32, 36.

• Psalm 110: 1-4.

• Matthew 16: 13-19.

… or, any lessons from the common of Pastors for a Pope.

|

|

If a Mass for St. Mary Magdalene dé Pazzi is taken, lessons from the feria as above, or from the proper:

• I Corinthians 7: 25-35.

• Psalms 148: 1-2, 11-14.

• Mark 3: 31-35.

… or, any lessons from the common of Virgins for One Virgin, or the common of Holy Men & Women for Religious.

|

The Third Class Feast of Saint Gregory VII, Pope & Confessor; and, the Commemoration of Saint Urban I, Pope & Martyr.**

Lessons from the common "Si díligis me …" for One or Several Holy Popes, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Peter 5: 1-4, 10-11.

• Psalm 106: 32, 31.

• Matthew 16: 13-19.

|

If a Mass for the Commemoration is taken, the same lessons as above.

|

FatherVenditti.com

|

7:11 AM 5/25/2019 — Of the three saints whose memorials all fall on this day—and from which the Roman Missal allows us to choose—I've chosen who is probably the least popular, Saint Bede. I know very little about Mary Magdalene de' Pazzi, and I doubt any of you were hankering for Pope Saint Gregory VII. But Father Bede is by far my favorite. 7:11 AM 5/25/2019 — Of the three saints whose memorials all fall on this day—and from which the Roman Missal allows us to choose—I've chosen who is probably the least popular, Saint Bede. I know very little about Mary Magdalene de' Pazzi, and I doubt any of you were hankering for Pope Saint Gregory VII. But Father Bede is by far my favorite.

Born in England in 672, he entered the Benedictine monastery of Saints Peter and Paul in Northumberland in the remote North of England where he is remembered as the happiest monk anyone ever encountered; but, that's not why he's a saint, and certainly not why he's my favorite, as I've clearly made no attempt to imitate his jovial nature, as I'm sure you've noticed. He was a tremendous theologian and scholar, whose writings are so full of sound doctrine that he was known as “venerable” even while he was still alive. He wrote treatises on theology, as well as many commentaries on Holy Scripture; and, if you've found anything erudite about the Scriptures in my homilies, you should give a lot of the credit to Saint Bede. In fact, I'd go so far as to say that, next to Saint Jerome, no one knew the Bible better.

But, his most influential writings by far are his historical works. He is, in fact, recognized as the “Father of English History” even by non-Catholics, and most of what we know about the history of England before the seventh century we owe to Bede. When we are reading or discussing historical events, we use the abbreviations BC, meaning “before Christ,” and AD, meaning anno Domini or “the year of the Lord,” automatically without thinking, completely oblivious to the fact that we owe our debt for those convenient designations to Saint Bede, who invented them. There's been a movement in the last fifty years or so by secularists to replace those designations with abbreviations which don't refer to Christ: CE for “common era” and BCE for “before the common era”; but, we owe it to Saint Bede, I think, to do all we can to resist that anti-Christian movement.

But, what I really want to offer you today is a reflection on our Gospel lesson from John.

It’s important to remember that the Blessed Apostle John, in his account of the life of our Blessed Lord, plays fast and loose with the chronology of events, compressing a public life of three years into one, and often rearranging events so as to follow certain themes. Many of the Gospel lessons we've been hearing at Holy Mass during this season purport to come from our Lord's last discourse to His Apostles at the Last Supper, and today Saint John offers us the conclusion of this speech, in which our Lord reminds his disciples that the hatred the world has for Him will translate to whomever follows Him, so that they should expect to endure persecution.

Comparing these chapters of John's Gospel with the other three Gospels, it's pretty clear that Saint John has taken sayings and sermons said by our Lord at various times during His public ministry and inserted them into his Last Supper narrative in a form of poetic license;—it is unreasonable to assume that our Lord's Apostles could have sat through a dinner speech of this length without some sort of intermission—but, we must admit that, rearranged by Saint John, outside of their original context, our Lord's words do take on a whole new meaning.  This is wholly consistent with the thematic thrust of John's Gospel, which is concerned not so much with presenting the facts of our Blessed Lord's life, as are the other three, but with serving more as a theological and spiritual reflection on the life of our Lord. John, after all, was the last survivor of the original twelve; his Gospel was written after most of his brother Apostles were dead. In the twilight of his years, he pens his Gospel, along with the Book of Revelation, to serve as a final testament to the meaning of our Lord's life on earth; and, many of the themes found in those books are mirrored by his own Epistles to the Churches that he had established. This is wholly consistent with the thematic thrust of John's Gospel, which is concerned not so much with presenting the facts of our Blessed Lord's life, as are the other three, but with serving more as a theological and spiritual reflection on the life of our Lord. John, after all, was the last survivor of the original twelve; his Gospel was written after most of his brother Apostles were dead. In the twilight of his years, he pens his Gospel, along with the Book of Revelation, to serve as a final testament to the meaning of our Lord's life on earth; and, many of the themes found in those books are mirrored by his own Epistles to the Churches that he had established.

So, in the Gospel lesson of today's Mass we come to what Saint John clearly regards as the punch-line: “If the world hates you, be sure that it hated me before it learned to hate you” (15: 18 Knox). John, after all, has already seen nearly all of his brother Apostles murdered by the enemies of Christ. He has already seen the various Churches they established ripped apart by dissension and heresy. He has already seen the spectacle of Christians turning on one another, denouncing one another, appealing to Peter against one another. Part of that whole saga was presented to us all this week in the first lessons from Acts, which concludes the whole history of Paul, Barnabas and Cornelius converting the Gentiles, then having to defend their actions at the First Council of Jerusalem.

So, when Saint John finally pens his Gospel, he's reflecting not only on the life of our Blessed Lord as he remembers it, but on everything that's happened in the life of the Church since, much of which was not pretty. Some might make a comparison to a lot that’s happening in the Church today.

While we might be tempted to view the Church in a state of confusion today, it can be some consolation to us to recognize that what we're going through now is nothing compared to what we've been through at various times in the past. Like Archbishop Gregory said at his installation the other day: the crisis and scandals from which we currently suffer are not all the chapters of our story and do not define us. To that I would add that we are defined by not just the totality of our history as a Church, much of which was much worse than the present, but also by our aspirations for the future, which are limitless. Christ promised us that He would be with us until the end of time, and throughout history He has shown us how He often raises up great saints to lead His flock out of dark times. Let’s agree to rely on the promise of our Lord, and face the future with the confidence that behooves a people of faith.

* A Benedictine from Tuscany, Pope Saint Gregory VII promulgated a reform against the evils of clerical marriage, simony (the granting of ecclesiastical offices to friends and relatives, or the buying and selling of the same), lay investiture (the appointment of bishops by monarchs), and greatly expanded the practical authority of the Holy See over local Churches, all of which put him on a collision course with the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV, whom he eventually excommunicated, and who exiled Pope Gregory from Rome in revenge. He died in exile in 1085; but, the veto authority of kings over the appointment of bishops was effectively ended due to his efforts, and is regarded as the turning-point in medieval civilization.

Mary Magdalene de' Pazzi was a Carmelite mystic from Florence who led a hidden life of prayer and self-denial, praying particularly for the reform of the Church and encouraging her fellow sisters in holiness. Instrumental in the reform of the Camelite Order, she died in 1607.

** Pope St. Urban suffered martyrdom in AD 230.

|