The Joy of Perseverance.

The Fifth Sunday of Easter.

Lessons from the tertiary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Acts 14: 21-27.

• Psalm 145: 8-13.

• Revelation 21: 1-5.

• John 13: 31-35.

The Fourth Sunday after Easter.*

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• James 1: 17-21.

• [The Gradual is omitted.]

• John 16: 5-14.

FatherVenditti.com

|

8:35 AM 5/21/2019 — No one can live without joy. That seems like an obvious statement, but you'd be surprised. Or maybe I think it needs stating because I'm a priest and tend to meet people—some people—only in the desperate moments of their lives. I remember, years ago when I was a hospital chaplain, I had my own parking space near the entrance to the emergency department, so whenever I went to the hospital I walked in through the emergency entrance; and, whenever I walked through the emergency waiting room on my way to my office, somebody sitting there would see me and start crying, because they had brought someone into the emergency room and assumed that the presence of a priest meant that someone was dead. You might have a hard time relating because you're all church-goers, but for a lot of people, the inside of a church is something they see when a friend or relative gets married, when they have a baby baptized, or when somebody dies; and, a priest is someone you call when someone's about to check out. I don't know what some of these people think the life of a parish priest is like, that we just sit at home waiting for people to die so we have a reason to go out. Probably they don't think about it at all. 8:35 AM 5/21/2019 — No one can live without joy. That seems like an obvious statement, but you'd be surprised. Or maybe I think it needs stating because I'm a priest and tend to meet people—some people—only in the desperate moments of their lives. I remember, years ago when I was a hospital chaplain, I had my own parking space near the entrance to the emergency department, so whenever I went to the hospital I walked in through the emergency entrance; and, whenever I walked through the emergency waiting room on my way to my office, somebody sitting there would see me and start crying, because they had brought someone into the emergency room and assumed that the presence of a priest meant that someone was dead. You might have a hard time relating because you're all church-goers, but for a lot of people, the inside of a church is something they see when a friend or relative gets married, when they have a baby baptized, or when somebody dies; and, a priest is someone you call when someone's about to check out. I don't know what some of these people think the life of a parish priest is like, that we just sit at home waiting for people to die so we have a reason to go out. Probably they don't think about it at all.

This is a true story: I went to visit an elderly parishioner of mine who had this really nasty son. He had been married and divorced a couple of times, and it was easy to see why: the kind of guy who was always suing his neighbors whenever their dog would poop on his lawn or their leaves would blow onto his driveway … you know the type, I'm sure … perpetually angry at the world around him for no particular reason. Every couple of months he would get himself arrested for being drunk and disorderly or starting a fight with someone. I never could figure out why he was like that, because she was a lovely person, as kind and gentle as she could be. He didn't visit his mother much, but I used to stop by almost every week because she was home-bound and only lived a couple of doors down from my church. When she knew I was coming she would leave the door unlocked, and I would just walk in, and one day I walked in and he was there. And he looked at me and said, “What are you doing here? There's nobody dead here.”

And I walked right up into his face and said, “There's about to be.” He didn't know what to do; he just walked out.

So, there certainly are people who live joyless lives. We know them. Joylessness is like the old chewing gum you pick up on your shoe: you can't get rid of it. The joyless person darkens every room he enters for everybody; and, for those who have married a joyless person, all of life seems like it's lived in a darkened room, because the joyless person is subconsciously jealous of those who are not joyless. He doesn't consciously intend it, but in order to preserve himself in his joylessness, he involuntarily finds a way to neutralize whatever joy or happiness may be present in any given situation. I keep saying “he,” but women can be this way just as often as men.

If life consisted only of funerals without weddings, of work without vacations, the burden of human existence would be unbearable for most of us; for the joyless person, a happy occasion is his Kryptonite: he has to find a way to ruin it, because if he can't he has no power over the situation; and that's a clue as to why the joyless person is the way he is:  deep down inside the joyless person feels inadequate, unaccomplished, unsuccessful; and, radiating his misery to everyone around him is his way of gaining control over a situation that potentially could expose his profound failure as a human being. deep down inside the joyless person feels inadequate, unaccomplished, unsuccessful; and, radiating his misery to everyone around him is his way of gaining control over a situation that potentially could expose his profound failure as a human being.

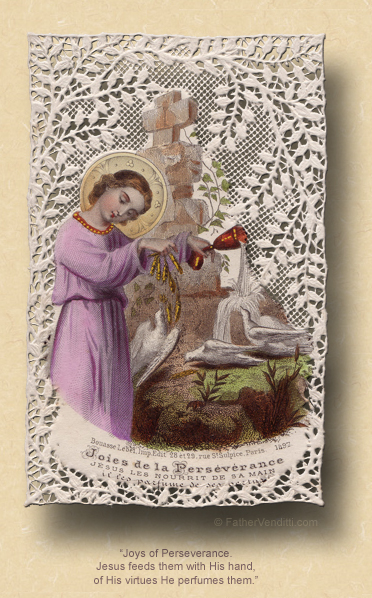

Today's first lesson presents to us the culmination of the lessons from Acts we've been reading all week long—for those who attend daily Mass—showing the Blessed Apostles Paul and Barnabas returning to some of the Churches they had established to encourage them to persevere in the faith in spite of hardships; and, they end up in Antioch, where Peter had already established a vibrant Church, where their report of their activities is received with great joy; but, we know that, by the time they get to Jerusalem, it's a different story, because most of the converts Paul and Barnabas made were Gentiles, and the Church of Jerusalem consisted exclusively of Jews. For the rest of his life Paul would labor among the Gentiles, making converts, consecrating bishops, setting up Churches, all the while having people from the Church's headquarters in Jerusalem follow in after him to try and undo everything he had accomplished. Part of the reason was theological;—a large segment of the Jerusalem Church still clung to the notion that Christianity was for Jews, and one couldn't be a Christian until one had been circumcised and professed the Jewish faith—but, part of it was psychological: the Jerusalem Christians knew that their parochial vision and narrow experience would never be able to penetrate the Hellenistic minds of people in sophisticated cities like Lystra, Iconium, Pisidia, Pamphylia, Perga, Attalia, all commercial trading centers steeped in Greek culture and philosophy. Paul, remember, had been a Pharisee, which made him most likely the best educated of all the Apostles, and he could figure out how to reach these people. The Jerusalem Christians knew they could never do what he had done; so, in their joylessness, they figured that if they couldn't do it, they sure as heck weren't going to let him get away with it. Even after Peter, who was the Pope, sided with Paul and made it clear that Paul had his support, it still went on behind the scenes.

None of this was hidden from Paul; he knew all along that this was going on, and said as much when he and Barnabas returned to all these places, as recorded in our first lesson: “They strengthened the spirits of the disciples and exhorted them to persevere in the faith, saying, 'It is necessary for us to undergo many hardships to enter the kingdom of God'” (Acts 14: 22 NABRE). Truer words were never spoken, but his choice of words is crucial: …quoniam per multas tribulationes oportet nos intrare in regnum Dei:  “…it is necessary for us to undergo many hardships to enter the kingdom of God”; two important points made in one very short phrase: not only that it's necessary to undergo hardship—that there is no way to follow our Lord without doing so—but also for a particular reason: “to enter the kingdom of God,” meaning that our reward for enduring this suffering is heaven, and not some consolation here on earth. “…it is necessary for us to undergo many hardships to enter the kingdom of God”; two important points made in one very short phrase: not only that it's necessary to undergo hardship—that there is no way to follow our Lord without doing so—but also for a particular reason: “to enter the kingdom of God,” meaning that our reward for enduring this suffering is heaven, and not some consolation here on earth.

Holy Mother Church puts the cap on this narrative by offering us a Gospel lesson taken from our Lord's homily at the very first ever Mass, the Last Supper, and Msgr. Knox's translation is the best: “The mark by which all men will know you for my disciples will be the love you bear one another” (John 13: 35). I'm guessing that in most churches today the priest will focus on this lesson exclusively and preach about how important it is to love one another, and I'm certainly not contradicting that; but, within the context of the totality of the Liturgy today, it's clearly meant by the Church as our Lord's own commentary on the behavior of the Christians in Jerusalem, who felt it was more important to preserve their superiority than to allow a couple of upstarts to show them up. It's even ratified in the old Catechism: what are the for marks of the Church? That it she one, holy, Catholic and apostolic. That's why I like Msgr. Knox's translation of the verse: “The mark by which all men will know you for my disciples will be the love you bear one another.” The first “mark” of the Church is her unity.

Which brings us back to our treatment of joy and those who spare no expense to try and live out their lives without any. Having accomplished nothing of their own accord, they must find a way to cancel whatever joy they perceive in the accomplishments of others. But putting up with them is part of our Christian duty, and the example was given to us by the greatest of our Lord's Apostles, who never despaired or turned back even when everyone—and I mean everyone—was against him, even to the point of telling his own converts that they should buck up and be ready for the same thing to happen to them. And what was the reason he gave that they should do this? that they should stay in the Church even though it was the Church, herself, that was trying to drive them out? So that they may “enter the Kingdom of God,” more beautifully put by Saint John in today's second lesson from Revelation, which we haven't yet looked at; and, again, Msgr. Knox nails the translation better than anyone, highlighting exactly why the Church will always be our home no matter what:

Here is God’s tabernacle pitched among men; he will dwell with them, and they will be his own people, and he will be among them, their own God. He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and there will be no more death, or mourning, or cries of distress, no more sorrow; those old things have passed away (Rev. 21: 3-4 Knox).

* In the Missal of St. John XXIII, the Fourth Sunday after Easter means the fourth after the Octave, in effect the fifth of the Easter Season.

|