The Forgotten Virtue.

The Seventh Sunday of Easter.*

Lessons from the secondary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Acts 1: 15-17, 20-26.

• Psalm 103: 1-2, 11-12, 19-20.

• I John 4: 11-16.

• John 17: 11-19.

The Sunday after the Ascension.

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Peter 4: 7-11.

• John 15: 26-27; 16: 1-4.**

The Sunday of the Fathers at the First Nicean Council; and, a Postfestive Day of the Ascension.

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the typicon of the Byzantine-Ruthenian Rite:

• Acts 20: 16-18; 28-36.

• John 17: 1-13.

FatherVenditti.com

|

9:52 AM 5/17/2015 — Last Thursday, when we celebrated the Solemnity of the Ascension of our Blessed Lord—and I know for a fact that every single one of you was at Holy Mass that day somewhere because it was a Holy Day of Obligation—I shared with those here some reflections on an image of the Risen Christ I had seen in a church out in the mid-west, in the middle of what we call the “farm belt”; it's a bronze statue of our Blessed Lord rising out of an ear of corn. The church where I found it was one of those architectural monstrosities so common in the early '70s, when everyone presumed that Vatican II meant that the past was evil and that the whole Catholic religion had to be reinvented from scratch. The artist, consistent with the mentality of those unfortunate times, crafted an image of our Lord that he felt would be relevant to those who worshiped there. The obvious fact of human nature that the artist totally forgot was that the familiar, while certainly relevant, is not uplifting. To a corn farmer who has spent his whole week in the hot sun wading among ears of corn for miles around, the last thing in the world he wants to see when he walks into church is another ear of corn, especially when the ear of corn is pretending to be his God. It's relevant, certainly, but in the wrong way. 9:52 AM 5/17/2015 — Last Thursday, when we celebrated the Solemnity of the Ascension of our Blessed Lord—and I know for a fact that every single one of you was at Holy Mass that day somewhere because it was a Holy Day of Obligation—I shared with those here some reflections on an image of the Risen Christ I had seen in a church out in the mid-west, in the middle of what we call the “farm belt”; it's a bronze statue of our Blessed Lord rising out of an ear of corn. The church where I found it was one of those architectural monstrosities so common in the early '70s, when everyone presumed that Vatican II meant that the past was evil and that the whole Catholic religion had to be reinvented from scratch. The artist, consistent with the mentality of those unfortunate times, crafted an image of our Lord that he felt would be relevant to those who worshiped there. The obvious fact of human nature that the artist totally forgot was that the familiar, while certainly relevant, is not uplifting. To a corn farmer who has spent his whole week in the hot sun wading among ears of corn for miles around, the last thing in the world he wants to see when he walks into church is another ear of corn, especially when the ear of corn is pretending to be his God. It's relevant, certainly, but in the wrong way.

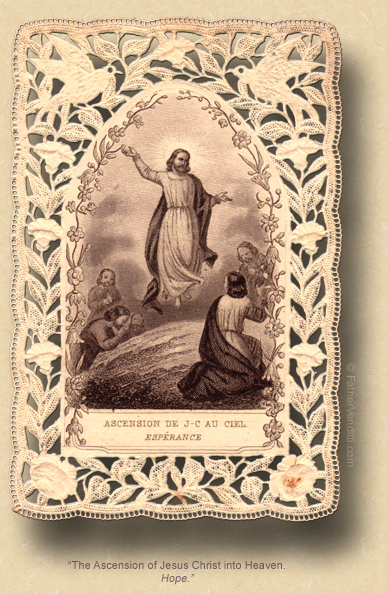

This is, I think, the most important lesson we learn from celebrating our Lord's bodily Ascension into heaven: that no matter how hard we try to make our faith practical and down-to-earth, the simple fact is that to be a Christian means to live in hope of another life which is very different from this one. That's why I like to call the feast of the Ascension the feast of the virtue of Hope; but, how many of us question how well we cultivate the virtue of Hope? That's why I often refer to the virtue of Hope as the forgotten virtue: we all know to pray for an increase in Charity, we all know we need to pray for an increase in Faith, but how many of us stop to consider whether we have cultivated the virtue of Hope? I'm going to come back to that in a moment.

But, that being said, we live in a world of practical concerns, where the theological virtues of Faith, Hope and Charity seem like the subjects of a theological seminar rather than something that pertains to our daily life. In point of fact, today's first lesson, from the Acts of the Apostles, shows the early Church struggling to deal with a very practical concern. Judas was one of the twelve Apostles of our Lord. As Saint Peter tells the assembled brethren, “Judas was counted among our number, and had been given a share in this ministry of ours” (1: 17 Knox). But after he betrayed our Lord, Judas took his own life, as you know, which left only eleven Apostles remaining; and, in his own brand of Biblical exegesis, Peter harkens back to the words of King David, quoting Psalm 108: “Swiftly let his days come to an end, and his office be entrusted to another” (v. 8 Knox); an artificial use of Scripture to be sure; but, I'm not about to question the first Vicar of Christ on how he chooses to interpret the Old Testament. The bottom line is that Saint Peter, the first Pope, had decided that Judas needed to be replaced;—whether that's justified by quoting the Psalms, Peter, I'm sure, will explain to me when I see him face to face on the day of my own judgment—and, our lesson from Acts recounts for us the process through which the Apostles chose Saint Matthias as Judas' replacement.

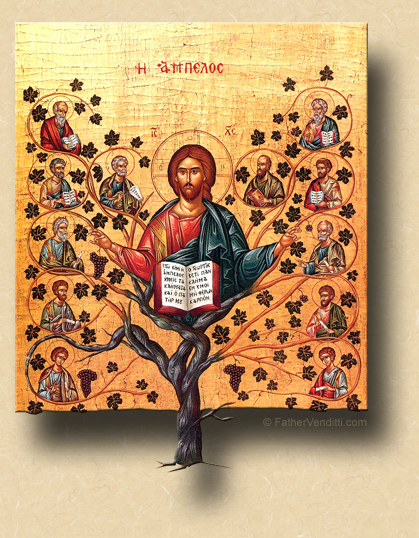

There is an important point here about which I think it is important for us to reflect. Why is it so important to Peter that there be twelve Apostles? Why can't the Church make due with eleven Apostles? Why can't there be thirteen Apostles, for that matter? Why not twenty-six Apostles? What's so special about the number twelve? The answer is obvious, and you know it already: there has to be twelve Apostles because Jesus chose twelve Apostles.  The number of Apostles was established by Christ, Himself. And so we see, very early in the life of the Church, right on the heals of our Lord's bodily Ascension, the pattern being established by which the institution of the Church forms itself, under the leadership of the first Pope, to imitate the practice of Christ her Head. To be sure: when Saint Paul called the Church the Body of Christ, he wasn't simply engaging in literary hyperbole; the Church is Christ, and Christ is the Church, and the Church must always do as Christ has done. The number of Apostles was established by Christ, Himself. And so we see, very early in the life of the Church, right on the heals of our Lord's bodily Ascension, the pattern being established by which the institution of the Church forms itself, under the leadership of the first Pope, to imitate the practice of Christ her Head. To be sure: when Saint Paul called the Church the Body of Christ, he wasn't simply engaging in literary hyperbole; the Church is Christ, and Christ is the Church, and the Church must always do as Christ has done.

Now, as obvious as this sounds to you and me, you'd be surprised—I hope—to realize how many there are in the Church today who take issue with this. I did my minor seminary training out in Kentucky, where I took my degree in philosophy;—in those days, you had to have a bachelor's degree in philosophy before you could be admitted to the major seminary, and St. Pius X in Kentucky was one of the last minor seminaries that offered that degree, which is how I ended up there—and, the bishop of Covington, Kentucky, at the time was old, crusty Bishop Ackerman; he's been dead many years now, so I can talk about him. When you met him for the first time, he scared the daylights out of you: he had this perpetual scowl on his face, and every word out of his mouth was some kind of bark or growl. In reality, he was a very kind and grace-filled man whose bark was much worse than his bite; but, you couldn't realize that until you took the time to get to know him. And this was back in the late '70s and early '80s when so many strange things were happening in the Church and everyone was confused. And someone asked Bishop Ackerman, “Why can't a woman be a priest?” And we all smiled to ourselves because we knew that the poor sap who asked this question was about to get a lightening bolt shot up his rear end. And Bishop Ackerman slowly leaned right into this poor guy's face, and growled, “For the same reason a tree trunk can't be a priest.”

Now, you could never get away with saying that today because it would be grossly offensive, and I would never respond to that question that way; but, what Bishop Ackerman was saying, in his own peculiar manner, was what the Church has understood since the time of Peter: a woman cannot be a priest because the female of the human species is invalid matter for the sacrament of the Holy Priesthood. Why must bread and wine be used in the celebration of the Holy Eucharist? Why can't you say Mass using a chocolate chip cookie and orange juice? Because Jesus, at the Last Supper, didn't use a chocolate chip cookie and orange juice; He used bread and wine. Only bread and wine is valid matter for the sacrament of the Holy Eucharist, because that's the way it was instituted by Christ. If Jesus had made a woman one of His twelve Apostles, then the Church could ordain women to the Holy Priesthood today, but he didn't. It's ironic, because—and I know this from my years as a pastor—in the Church today, the only people you can depend on to get anything done when it needs to be done are the women. The men are great for throwing out ideas and telling the priest what they think he should do, but they're useless when it comes to actually doing anything; it's the women who typically do all the work. That being said, they can't be priests, and it has nothing to do with their personal suitability; and, even if some renegade bishop somewhere were to lay his hands on the head of a woman and pronounce the sacramental words that normally make a priest, she would not become a priest, because the sacrament of the priesthood cannot exist in her. It isn't a “rule” or “regulation” of Canon Law that women cannot be priests; it's a sacramental fact … just as it's a sacramental fact that, if I were to stand here in front of you and pronounce the words of consecration over a chocolate chip cookie and orange juice, it would not become the Blessed Sacrament.

When Peter, in our first lesson today, insists that the brethren must choose a replacement for Judas so that the number of Apostles is restored to twelve, he is declaring that even he, as Pope, cannot do whatever he wants, but must act in accord with what was done by Christ, Himself.

Which brings us back to the feast of the Ascension, and that forgotten virtue, the virtue of Hope. We happen to be blessed—or cursed, however you choose to look at it—to live in a very tumultuous and confusing time, perhaps even more so than the '70s were. Some of us, I know, are often confused and perplexed by things we think are said or done by the Holy Father;—I say “think” because what we hear on the news on TV is almost always inaccurate—and, I know we're all distressed by the wholesale persecution of the Church going on in the Middle East and even, to an extent, here at home, with the government trying to take away the rights of believers in almost every sphere of American life.  But all of this is nothing more than a test of how well—or how poorly—we have cultivated the virtue of Hope. Jesus ascends into the heaven from which He came in the first place, and there he sits, at the right hand of the Father, ready to plead our cause on the day of judgment. And there he is in heaven with a room waiting just for us, one with our name on it. Sure, it's a nice thing to live a happy carefree life. But you know what? It's not necessary. Our life on earth, compared to heaven, is like a second compared to a billion years. But all of this is nothing more than a test of how well—or how poorly—we have cultivated the virtue of Hope. Jesus ascends into the heaven from which He came in the first place, and there he sits, at the right hand of the Father, ready to plead our cause on the day of judgment. And there he is in heaven with a room waiting just for us, one with our name on it. Sure, it's a nice thing to live a happy carefree life. But you know what? It's not necessary. Our life on earth, compared to heaven, is like a second compared to a billion years.

Now, in saying that, I'm not trying to trivialize the hardships of life. Simply knowing that life is short and that heaven is our destiny doesn't necessarily cause us to accept all our sufferings here on earth joyfully and without complaining. It would if we were saints, but most of us aren't. So, we complain, and we worry, and we convince ourselves that life isn't fair. That's part of who we are. Please God, one day we will look back on earth from our places in heaven and realize how silly it all was. In the mean time, Christ ascends into heaven leaving a path for us to follow. He sends the Holy Spirit to help make sure we stay on the path. He established the Church through which the Holy Spirit acts on this earth, and He appointed the Apostles through which the Spirit teaches us what we need to know.

Between now and the time that each of us is judged by God as worthy or unworthy of heaven, we will have a lot to occupy our minds and our time. What's important is that we never lose sight of the ultimate destination, and how we must live in order to get there. As the Scriptures say so many times, heaven is our true home. As long as we're on this earth we are simply on a journey. And the best part of any journey is arriving home.

In today's Gospel lesson, Jesus, just before ascending into heaven, prays to His Father, and speaks of us:

I have given them thy message, and the world has nothing but hatred for them, because they do not belong to the world, as I, too, do not belong to the world. I am not asking that thou shouldst take them out of the world, but that thou shouldst keep them clear of what is evil (John 17: 14-15 Knox).

And why would we ever presume that God would not do exactly that? And right after He prays this prayer, just seconds before He ascends into heaven, Jesus turns to His disciples—and us, because we are His disciples, too—and makes us this promise:

All authority in heaven and on earth, he said, has been given to me; you, therefore, must go out, making disciples of all nations, and baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, teaching them to observe all the commandments which I have given you. And behold I am with you all through the days that are coming, until the consummation of the world (Matt. 28: 18-20 Knox).

* In the Metropolitan Province of Newark, New Jersey (Archdiocese of Newark, Dioceses of Camden, Metuchen, Paterson & Trenton), in the ordinary form of the Roman Rite, the Ascension of Our Lord is celebrated on its traditional date, on the Thursday following the Sixth Sunday of Easter, and is not transferred to the Seventh Sunday as in most dioceses in the United States.

** The Gradual Psalm continues to be omitted throughout Ascensiontide, through the end of the Octave of Pentecost, but resumes during the rest of the Pentecost season.

|