We Aren't Forgiven Because Jesus Is Nice.

The Fifth Monday of Lent.

Lessons from the feria, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Daniel 13: 1-9, 15-17, 19-30, 33-62.

[or, Daniel 13: 41-62.]

• Psalm 23.

• John 8: 12-20.*

Passion Monday.**

Lessons from the feria, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Jonah 3: 1-10.

• [Gradual] Psalm 53: 4, 3.

• [Tract] Paslm 102: 10.

• John 7: 32-39.

FatherVenditti.com

|

7:45 PM 4/8/2019 — Here’s a little something that no one ever thinks about—which means that my twisted mind will think about it.

Ordinarily, the Gospel lesson read on this fifth Monday of Lent is Saint John’s account of the woman caught in adultery, which seems to dovetail nicely with the saga of Susanna from Daniel through which we just suffered; but, inasmuch as that passage from John was read yesterday this year, we have been given a different Gospel lesson which consists of the verses immediately following;  which, taken out of context, don’t seem to relate at all except for our Lord’s mention of the prescript from Leviticus 17 about the veracity of two witnesses, which the elders’ in our first lesson use to attempt to condemn Susanna. I suppose in the mind of some post-counciliar liturgist that made sense. The old liturgy has no problem with repetition and doesn’t presume that, if we hear the same passage two days in a row, we will all turn into pumpkins. which, taken out of context, don’t seem to relate at all except for our Lord’s mention of the prescript from Leviticus 17 about the veracity of two witnesses, which the elders’ in our first lesson use to attempt to condemn Susanna. I suppose in the mind of some post-counciliar liturgist that made sense. The old liturgy has no problem with repetition and doesn’t presume that, if we hear the same passage two days in a row, we will all turn into pumpkins.

Be that as it may, given the length of today’s first lesson, I will offer you only one very brief reflection. Keeping in mind that today’s Gospel lesson is part of the extended narrative of our Lord rescuing the woman caught in adultery, I would like to offer the profound contrast between her and Susanna, and the implications that presents regarding how we must view our own sinfulness and redemption. What’s the primary difference between Susanna and the woman caught in adultery? Obviously, Susanna is innocent; the woman from John’s Gospel is—to coin a cliché—guilty as sin, as evidenced by what the Pharisees tell our Lord: that she was caught “in the very act.” No mention is made about how they came to catch her in the act, and one commentator I read suggested it may have been because one of them was the one with whom she was committing adultery. But that’s not the point.

The point is that both Susanna and the adulterous woman are vindicated: Susanna after receiving justice, and the adulterous woman after receiving forgiveness. They both walk away Scott-free, the adulterous woman albeit with a warning not to sin again. It’s a striking contrast between the ethics of the Old Testament and the redemption offered to us by Christ, which is why I’m anxious whenever I hear anyone talking about a shared Judeo-Christian ethic, because the two seem diametrically opposed. Our Lord specifically canceled “an eye for an eye” and replaced it with “go and sin no more.”

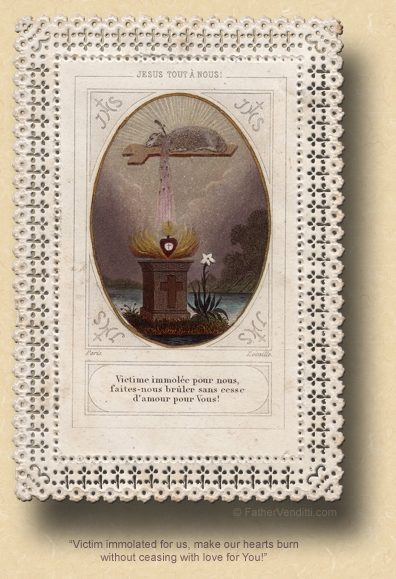

And this should be a great consolation to us as Lent winds down and we have further opportunity to contemplate our sins. Justice works both ways: Susanna got justice because she was innocent, but where was justice in the case of the adulterous woman? She was guilty of a very serious sin, and yet God did not receive His justice … except that He did, really. Who was it that absolved her from being punished? It was our Lord Himself, Who actually did pay the penalty for all of our sins. He had not done it yet at the time He forgave the woman; but, He’s God, so He’s not restricted to the rules of time and space. So, justice was served in her case: instead of her being stoned to death, Jesus took her place and died for her, exactly as he does for all of us, which is precisely why we can avoid going to hell even in spite of our sins.

The forgiveness of our sins does not mean that Jesus doesn’t care about punishing us and we all get away Scott-free because He’s nice; it means that He took our punishment for us.

* Ordinarily, the Gospel lesson for this day is John 8: 1-11, the account of the woman caught in adultery; but, inasmuch as that lesson was read yesterday, the Missal indicates that it is replaced by this one whenever the Sunday cycle is of the tertiary dominica. If, on the other hand, the option to always read the lessons from the primary dominica on the fifth Sunday (the raising of Lazarus) was taken, then the lesson of the woman caught in adultery would be read today.

** In the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite, the Fifth Sunday of Lent, known as the First Sunday of the Passion or simply Passion Sunday, begins the brief season of Passiontide, which is distinguished from the rest of Lent, and which culminates in the Second Sunday of the Passion, known as Palm Sunday. In the ordinary form, the season of Passiontide has been eliminated, and the liturgical themes of both Sundays of the Passion have been combined into a single Sunday known as Palm Sunday; in fact, in some early editions of the Missal of St. Paul VI, Palm Sunday is listed as Passion Sunday. The Roman Missal Third Edition attempts to cover all the bases by designating the Sunday which begins Holy Week as "Palm Sunday of the Passion of the Lord."

|