This Preview Has Been Approved for All Audiences.

The Fifth Sunday of Lent.

Lessons from the primary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Ezekiel 37: 12-14.

• Psalm 103: 1-8.

• Romans 8: 8-11.

• John 11: 1-45.

[or, John 3-7, 17, 20-27, 33-45.]

The First Sunday of the Passion.*

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Hebrews 9: 11-15.

• [Gradual] Psalm 142: 9-10.

• [Tract] Psalm 128: 1, 4.

• John 8: 46-59.

The Fifth Sunday of the Great Fast, and of Our Holy Mother Mary of Egypt.**

First & third lessons from the triodion, second & fourth from the menaion, according to the Ruthenian recension of the Byzantine Rite:

• Hebrews 9: 11-14.

• Galatians 3: 23-29.

• Mark 10: 32-45.

• Luke 7: 36-50.

FatherVenditti.com

|

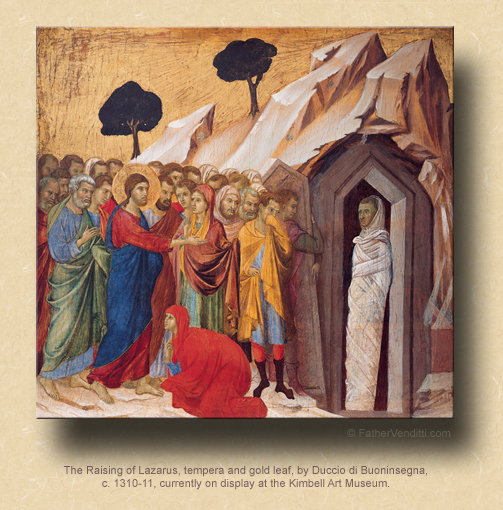

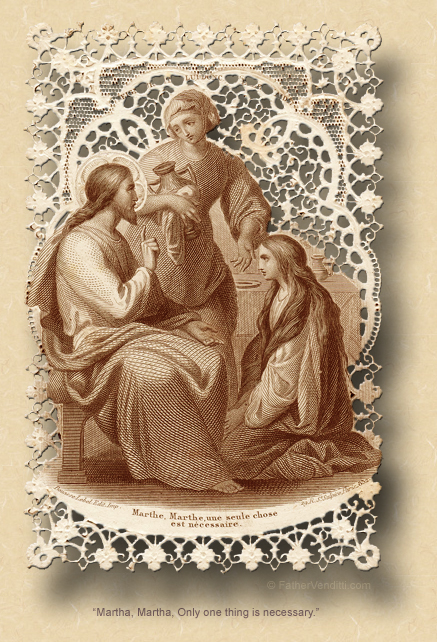

8:07 AM 4/2/2017 — In the Byzantine Church in which I served for nearly twenty years, Holy Week does not begin on Palm Sunday as it does in the Latin Church; it begins on the day before, which is called Lazarus Saturday, on which this Gospel lesson from Saint John is sung. The whole story actually begins in the next chapter (ch. 12), during what may have actually been a previous visit of our Lord to the home of His friend, Lazarus, and His two sisters, Mary and Martha (cf. Matt. 26: 6; Mark 14: 3; &, Luke 7: 36). It was on that occasion that Mary anointed our Lord's feet with perfumed oil and dried them with her hair, an event which is recalled at the beginning of the lesson we just heard, which suggests that, in his Gospel, Saint John has rearranged the sequence of events. 8:07 AM 4/2/2017 — In the Byzantine Church in which I served for nearly twenty years, Holy Week does not begin on Palm Sunday as it does in the Latin Church; it begins on the day before, which is called Lazarus Saturday, on which this Gospel lesson from Saint John is sung. The whole story actually begins in the next chapter (ch. 12), during what may have actually been a previous visit of our Lord to the home of His friend, Lazarus, and His two sisters, Mary and Martha (cf. Matt. 26: 6; Mark 14: 3; &, Luke 7: 36). It was on that occasion that Mary anointed our Lord's feet with perfumed oil and dried them with her hair, an event which is recalled at the beginning of the lesson we just heard, which suggests that, in his Gospel, Saint John has rearranged the sequence of events.

From both a historical and spiritual perspective, the Passion of our Lord actually begins not with His arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane as we will hear on Good Friday, but many weeks before, with the anointing of our Lord's feet by Lazarus' sister, Mary. At the time she's doing it, read out of context, it seems on the surface to be something she does purely out of love and devotion for our Lord; but, Saint John switches around the order of events because he so clearly wants us to understand what our Lord understood: that this was really the first stage of our Lord's burial rites. Jewish funeral custom requires that the body be dressed with perfumed oils prior to burial, but remember that this could not be done for Jesus after His death because it was the Sabbath and late in the day; that's why Mary, Mary and Salome go to the tomb on Easter Sunday: to perform this ritual retroactively, as it were.  They can't do it because they find the tomb empty, our Lord having already risen from the dead; but, even if He had not yet risen from the dead, it would have been impossible for them to do it because it had, in fact, already been done. That's what makes the anointing by Mary in the home of Lazarus significant: because it is, in fact, our Lord's burial anointing, even though He's not yet dead. And the reason the Byzantines read the raising of Lazarus at the beginning of Holy Week—and the reason we read it today—is so that we will understand that the triumphant procession of our Lord into Jerusalem, which we will read on Palm Sunday, is really a funeral procession, even though no one there at the time knew it … except Jesus Himself. They can't do it because they find the tomb empty, our Lord having already risen from the dead; but, even if He had not yet risen from the dead, it would have been impossible for them to do it because it had, in fact, already been done. That's what makes the anointing by Mary in the home of Lazarus significant: because it is, in fact, our Lord's burial anointing, even though He's not yet dead. And the reason the Byzantines read the raising of Lazarus at the beginning of Holy Week—and the reason we read it today—is so that we will understand that the triumphant procession of our Lord into Jerusalem, which we will read on Palm Sunday, is really a funeral procession, even though no one there at the time knew it … except Jesus Himself.

Which brings us to today's Gospel lesson, which is so obviously a prefiguring of our Lord's own resurrection from the dead … kind of like what we get in the movie theaters: a preview of a coming attraction. Saint John, having had the longest time of all the Evangelists to reflect on the life of our Lord, packs his account, as he always does, with heaps and heaps of allegory and spiritual innuendo, on which the Fathers of the Church of the first four centuries commented for volumes: from the appeal of Saint Thomas to the other apostles to go to Jerusalem and “die with Him” (11: 16), and how that would relate to his later doubts about the reports of our Lord's resurrection and the dramatic scene of meeting the risen Lord in the upper room, to the command of our Lord to unbind Lazarus from his winding sheets and “let him go free” (v. 44), four simple words on which one could speak for hours. Don't worry; my bladder will not permit it.

Now, having witnessed our Lord bringing Lazarus out of his tomb, we are ready for Palm Sunday, ready to enter with Jesus into Jerusalem, sharing with Him the full awareness of why He goes there. In the days to come, He will allow us to see His humiliation: the insults, the beatings, the flogging, and finally the crucifixion. We will see both the cowardice of Judas and the betrayal of Peter, reminding us of the fragile nature of our own dedication to Christ: if these chosen apostles can falter, then so can we, and we know it.

What was it, exactly, that saved Peter from his betrayal, but not Judas? Both were apostles, both were loved by our Lord, both betrayed Him; but, Peter was able to survive his betrayal with his faith intact. Judas, on the other hand, was so filled with remorse over what he had done that he was driven to take his own life.  And the answer might lie in the beginning of Saint John's elongated account of the Passion, in which Judas displays his vexation over the waste of the perfumed oil. Set aside for a moment the concept of this being our Lord's premature burial ritual. What is the essential difference between Judas' betrayal and Peter's? Peter's betrayal is one of pure human weakness. He's accused of being associated with Christ, and because he doesn't want to be arrested himself, he denies it. It's a pure act of self-preservation done in a moment of weakness. And the answer might lie in the beginning of Saint John's elongated account of the Passion, in which Judas displays his vexation over the waste of the perfumed oil. Set aside for a moment the concept of this being our Lord's premature burial ritual. What is the essential difference between Judas' betrayal and Peter's? Peter's betrayal is one of pure human weakness. He's accused of being associated with Christ, and because he doesn't want to be arrested himself, he denies it. It's a pure act of self-preservation done in a moment of weakness.

Judas, on the other hand, is not weak at all. His betrayal is grounded in—how does one say it gracefully?—his anal retentiveness. I guess one can't say it gracefully. Things are not perfect enough for him. Jesus has not marketed Himself very well; not enough has been said about the Roman occupation of Palestine; Jesus' decision to go to Jerusalem for the Passover was a bad one in his opinion; and now this waste of the apostolic funds on perfumed oil, money which he says, quite correctly, could have been given to the poor, even though we are told by Saint John that his motive was a greedy one.

The bottom line is that there's a difference between sinning out of weakness and sinning because one thinks one knows better. It's never a question of commitment to Christ: Peter and Judas were both equally committed to Christ, but Judas had to have it on his own terms. That's why the purpose of amendment in confession is so important: it's not enough to simply know that something I did was wrong; I have to agree that it's wrong; I have to—at the very least—want not to do it again, even if I know there's a strong possibility that I might fail. And if I do fail again, it has to be out of my own weakness, not because I have declared myself right and our Lord wrong.

So, today, with the raising of Lazarus—this preview of the resurrection fresh in our minds—we begin our long trudge up the mountain of Calvary with our Lord. Like our Lord, we will stumble and fall along the way; and, like our Lord, we will pick ourselves up and dust ourselves off and continue on, just as we do all our lives. The one difference between ourselves and both Peter and Judas is that we know with certainty that, at the end of the road, lies a glorious resurrection.

* In the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite, the Fifth Sunday of Lent, known as the First Sunday of the Passion or simply Passion Sunday, begins the brief season of Passiontide, which is distinguished from the rest of Lent, and which culminates in the Second Sunday of the Passion, known as Palm Sunday. In the ordinary form, the season of Passiontide has been eliminated, and the liturgical themes of both Sundays of the Passion have been combined into a single Sunday known as Palm Sunday; in fact, in some early editions of the Missal of Bl. Paul VI, Palm Sunday is listed as Passion Sunday. The Roman Missal Third Edition attempts to cover all the bases by designating the Sunday which begins Holy Week as "Palm Sunday of the Passion of the Lord."

** In the various Churches of the Byzantine Tradition, certain Sundays during the Great Fast are dedicated to the memory of specific individuals. In the sixth century, near the monastery of Sauca in Egypt, pilgrims venerated the tomb of a holy woman named Mary, who had lived in the desert as a hermit and a penitent. In the seventh century, Patriarch Sophronios of Jerusalem wrote a biography of this woman which served as the basis for all the subsequent literature about her life generated over the next few hundred years, and the stichera of First Vespers for this Sunday are based on that biography. It describes a woman who spent her youth as a prostitute, was converted to Christ, and spent the next forty-seven years living in the desert where she was routinely brought the sacraments and ministered to by some holy monks. Though scholars are quick to point out that there is no documentation to corroborate anything contained in the Patriarch’s biography of Mary of Egypt, that her tomb was a popular pilgrimage destination a hundred years earlier is certainly a historical fact. A previous homily for this Sunday on Mary of Egypt can be found here.

|