Letting Priests Be Priests, Version 2.5.

The Third Sunday of Easter.

Lessons from the secondary dominica, according to the ordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• Acts 3: 13-15, 17-19.

• Psalm 4: 2, 4, 7-9.

• I John 2: 1-5.

• Luke 24: 35-48.

The Second Sunday after Easter.*

Lessons from the dominica, according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite:

• I Peter 2: 21-25.

• John 10: 11-16.**

The Sunday of the Ointment-Bearing Women.

Lessons from the pentecostarion, according to the typicon of the Byzantine-Ruthenian Rite:

[At Vespers...]***

• Leviticus 19: 1-4, 9-15.

• Wisdom 1: 12—2: 6, 21-24.

• Exodus 40: 1-15.

• I Samuel 16: 1-13.

[At the Divine Liturgy...]

• Acts 6: 1-7.

• Mark 15: 43—16: 8.

FatherVenditti.com

|

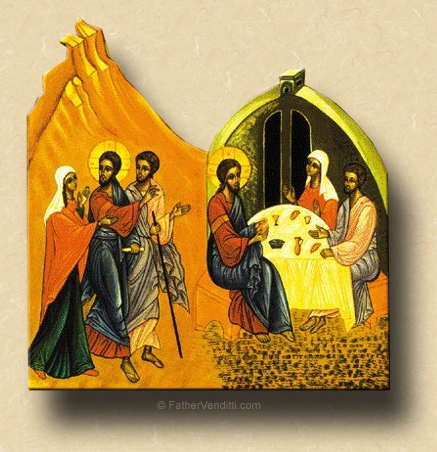

8:21 AM 4/19/2015 — Those of you who attend Holy Mass here every day will find this homily familiar, but that's because the lessons presented for Holy Mass on these Sundays after Easter are often read on weekdays as well, and today's lesson was read back on Easter Thursday. It begins with the line: “The two disciples recounted what had taken place on the way, and how Jesus was made known to them in the breaking of the bread” (Luke 24: 34 NABRE). The incident referred to is that familiar one of our Lord's encounter with the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, one of who is named Cleopas, and the other not named.  We've talked about them before: how they do not recognize our risen Lord, how they recount for Him the story of Christ's betrayal, passion and death, marveling at how He would not know about such things. As they get near the city, our Lord makes pretense of leaving them and continuing on, and they ask Him to stay with them; and, we observed at the time that our Lord's pretending to want to leave them and continue on was His way of testing their desire to be with Him: if they want Him to stay with them, they're going to have to ask. And we reflected that our Lord does this to us all the time, allowing us, in His permissive will, to suffer wants and needs and deprivations in order to train us to depend on Him rather than on ourselves. We've talked about them before: how they do not recognize our risen Lord, how they recount for Him the story of Christ's betrayal, passion and death, marveling at how He would not know about such things. As they get near the city, our Lord makes pretense of leaving them and continuing on, and they ask Him to stay with them; and, we observed at the time that our Lord's pretending to want to leave them and continue on was His way of testing their desire to be with Him: if they want Him to stay with them, they're going to have to ask. And we reflected that our Lord does this to us all the time, allowing us, in His permissive will, to suffer wants and needs and deprivations in order to train us to depend on Him rather than on ourselves.

He stays with these two disciples and, as Saint Luke puts it, He “broke bread” with them, which is Luke's subtle way of saying that He said Mass; and, it's in the context of this Mass, celebrated by our Lord, that they recognize Him, at which point He immediately disappears. He disappears because, with the Blessed Sacrament now present, there is no need for Jesus in His human form to hang around anymore. Having received our Lord in Holy Communion, these two then run off to Jerusalem to tell the Apostles what had happened; and, this is where today's Gospel lesson begins.

Now, I had also mentioned to those in attendance at daily Mass during Easter Week that most of those who encounter our Lord after His resurrection are unable at first to recognize Him; not Mary Magdalene, not the other women, and not these two disciples He meets on the road to Emmaus … at least not until He offers the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass in their presence, whereupon He immediately vanishes because there is no need for two manifestations of our Lord. In today's Gospel lesson, which is also by Saint Luke, he appears for the first time to His Apostles and, oddly enough, they do recognize Him, so much so that they think they're seeing a ghost. Why are they able to see what no one else could see? Simple. They're priests. They have a relationship to our Lord that no one else has; and, it's important to note that the risen Lord does not do for them what he did for the disciples in Emmaus: He does not say Mass for them; He doesn't have to because this is something that they're able to do for themselves.

Here's a little secret of which most of you are not aware:—except those who were here during the days of Easter week—prior to being ordained to the Holy Priesthood, every seminarian who has been ordained to the diaconate is required to write out in long hand a petition asking his bishop for ordination; and, in that petition, he must state the reason, and only one reason is considered valid. And it's not what you might think: it's not because he wants to help people, it's not because he wants to preach the Gospel, it's not because he wants to say Mass, it's not because he wants to serve the Church; it's not because he doesn't like girls and wants three meals and a flop; the only reason he's allowed to give—and which he must write out in his own hand—is, “…for the honor and glory of God and the salvation of my own soul.” In other words, he has to tell his bishop that he wants to be a priest because he has come to believe that, unless he becomes a priest, he will not be saved.

Now, we're not going to go into the historical reasons or theological implications of that fact, as interesting as they are; it's just by way of emphasizing the fact that the relationship of the priest to our Lord is different from the relationship of everyone else to our Lord, which is why the Apostles are able to recognize Jesus after His resurrection when everyone else could not, and why our risen Lord, upon meeting the Apostles for the first time after rising from the dead, does not say Mass for them as He did for the disciples at Emmaus who were not priests.

But, priests or not, they are still men with all the weaknesses and temptations of men; their priesthood does not make them holier than anyone else, and it certainly doesn't make them any smarter, which is why even while recognizing our Lord they are incredulous, and think they're seeing a ghost. So, what does He do? He eats a piece of fish. This is a significant act, because it illustrates the fact that our Lord's resurrection from the dead was not something mystical or ethereal, and His risen presence was not some sort of heavenly projection: a heart muscle which had ceased to beat began to beat again; lungs which had become empty filled with air again; blood which had ceased to flow coursed through His veins once again. His body was a glorified one—a perfected one—but it was still the same body. The resurrection of our Lord, God and Savior Jesus Christ is not a metaphor.

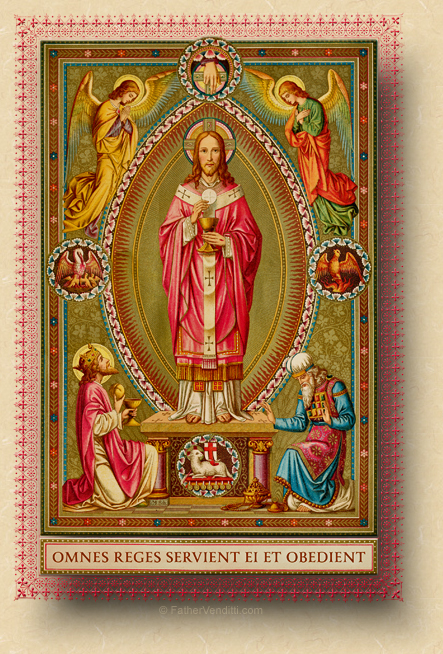

“O Lord, our God,” sings King David, “how glorious is your name over all the earth! What is man that you should be mindful of him, or the son of man that you should care for him?” (Psalm 8: 2, 5 NABRE). And what greater evidence of our Lord's care for us than the gift of Himself in the Blessed Eucharist, and what further evidence than the fact that He gave the power to make the Eucharist happen to His apostles who, through the laying on of hands, passed that power on to other men down through the centuries. The earliest evidence proves that, from the moment that they began to build churches, early Christians began to reserve the Blessed Sacrament in them; and, contrary to popular opinion, they did not do it simply because they needed the Sacrament on hand to take to the sick; they did it because they wanted to pray before our Lord in the tabernacle. And we know this from no less ancient a source than Saint John Chrysostom, who preached on Jesus entering the Temple in Jerusalem, saying, “This was proper to a good son: to enter immediately into the house of his Father to render due honor to Him there—just as you, who should imitate Jesus, whenever you enter a city should first of all go the church” (Catena Aurea, III).

We do not need to envy the Apostles who saw and recognized the Lord after His resurrection; we see Him every day. And we see Him because He gave us priests with the ability to make Him present to us in the Holy Sacrifice of the Altar … just as present to us as He was when He walked this earth as a man. And at the risk of boring those who are here every day, yesterday at Holy Mass we read Saint Luke's account, from the Acts of the Apostles, of the selection and ordination of the Church's first deacons.  They choose seven men to assume this office; and, what's the reason the Twelve give for the ordination of the Church's first deacons? They say, “It is not right for us to neglect the word of God to serve at table” (Acts 6: 2 NABRE). They were not running a restaurant. The Church, as it does to this day, cared for the poor; at Holy Mass, collections were taken up, just as they are today, and much of what was collected went to those in need, and this required a lot of footwork. The Apostles had been doing it all themselves, but it soon became clear that they couldn't give enough attention to preparing for and celebrating the sacred mysteries if they also had to be involved in all these charitable activities; so, the deacons were ordained to do this sort of work for them. They choose seven men to assume this office; and, what's the reason the Twelve give for the ordination of the Church's first deacons? They say, “It is not right for us to neglect the word of God to serve at table” (Acts 6: 2 NABRE). They were not running a restaurant. The Church, as it does to this day, cared for the poor; at Holy Mass, collections were taken up, just as they are today, and much of what was collected went to those in need, and this required a lot of footwork. The Apostles had been doing it all themselves, but it soon became clear that they couldn't give enough attention to preparing for and celebrating the sacred mysteries if they also had to be involved in all these charitable activities; so, the deacons were ordained to do this sort of work for them.

And what's important for us to notice is that, even in the time of the Apostles, there is already a well-defined division of labor in the Church: the job of the priest is to offer sacrifice and preach the Word of God; the more pragmatic duties of the Church are given to others, and specifically for the reason of leaving the priests free to perform their sacred functions.

I was a pastor for many years, and one of the most frustrating things about being a pastor is that most of what you do has nothing to do with being a priest: you're a maintenance man, you're a plant manager, you're an accountant, you're a social worker, you're a marriage counselor, you're a fund raiser, you're a plumber, you're a parking authority meter maid, you're everything except what you were ordained to be, which is a preacher of the Word and an offer-er of sacrifice. When Pope Blessed Paul VI reinstated the diaconate as a permanent ministry in the Church, no longer restricting it to seminarians in preparation for the priesthood, his idea was to correct this problem; but, it didn't turn out that way, as most of the deacons ordained since then are all married men with jobs and lives of their own, and whose ministry more or less consists of helping out at Holy Mass on Sundays, which, as Saint Luke's account clearly shows, had nothing to do with why they were chosen in the first place. There is no evidence that, in the early Church, the deacons had any liturgical functions; certainly in the Scriptures they had none. Now, in many parishes, we have battalions of lay people charging out to hospitals to take Holy Communion to the sick. Why? So the priest has time to attend meetings, pay all the bills and repair the boiler? To coin a cliché: What's wrong with this picture?

What I want to offer for your reflection today—and which, I admit, is a complete repeat from yesterday's Mass—is a simple and brief appeal to not only pray for priests every day, which I'm sure you do, but also encourage you to make a resolution to let your priests be priests. The Holy Priesthood is not an office of authority, but an office of service; he stands in the place of Christ as a victim for sin, one who leads us in prayer and presents to Almighty God the offering of sacrifice for the remission of sin on behalf of the souls entrusted to his care; and we should not attempt to draw him out of that role.

Take confession, for example. So many times we go into the confessional and start telling the priest about our problems, but that's not what he's there for; he's there, on behalf of Christ, to hear us accuse ourselves of our sins, impose whatever penance is appropriate, and impart to us our Lord's absolution. Why we sinned, what led us to sin, what we're feeling about our sins is not relevant. “Father, my daughter-in-law makes me so mad…” Except you're not there to confess your daughter-in-law's sins; you're there to confess your sins. Why you said something uncharitable to your daughter-in-law doesn't matter, and the priest has no need to know that; all he needs to know to absolve you is that you said it and that you're sorry.

At the end of that lesson from yesterday's Mass, Saint Luke tells us what the commission to these seven men to assume the more mundane tasks of the Church did: “The word of God continued to spread, and the number of disciples in Jerusalem increased greatly; even a large number of priests were becoming obedient to the faith” (6: 7 NABRE). Saint Luke is, of course, speaking of Jewish priests in that last sentence, but the irony of his choice of words should not be lost on us. If we have ever been concerned about the holiness of our priests, if we have ever wondered why this priest or that whom we may know is not what we think he should be as a priest of Jesus Christ, one of the reasons may be that we keep expecting him to be what he is not. After the example of our Lord, the priest is ordained to guide, to teach, and to sanctify. Everything else is—or at least should be—irrelevant for him.

So, let us pray for our priests, but—even more importantly—let us also resolve to let our priests be priests.

* The discrepancy between the designation of the days following Easter in the ordinary and extraordinary forms of the Roman Rite is due to the fact that, in the extraordinary form, the Octave Day of Easter (Low Sunday) is counted as part of Easter itself, and not designated as a Sunday “after Easter.” Thus, what the Missal of Bl. Paul VI calls the Third Sunday “of” Easter, the Missal of St. John XXIII calls the Second Sunday “after” Easter. The Missal of St. John XXIII gives no entries for ferial days, the texts and lessons all coming from the preceding Sunday; thus, this convention will be used where necessary for ferial days as well.

** In the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite, from Easter Saturday until the end of Paschaltide, the Gradual Psalm is omitted.

*** These Old Testament lessons for First Vespers on certain Sundays are a new innovation to the Ruthenian Church, and their use is optional. The typicon of the Ruthenian Church has begun to offer them, borrowing them from either the typicon of the Syrian Church, or from Fr. Theodore Pulcini's Old Testament Lectionary for Use in the Byzantine Tradition at Great Vespers on Saturday Evening, published in 2005. The lessons given for today are Syrian. The intention is to open a fuller reading of the Old Testament during the seasons of Pascha and Pentecost in which, traditionally, the Old Testament is ignored liturgically.

These readings would only be read when Vespers is celebrated by itself. The Ruthenian Church allows for an anticipated Divine Liturgy on Saturday evening for Sunday obligation, but requires that it always be combined with Vespers, calling the service a "Vigil Divine Liturgy," at which these optional lessons would not be read.

|